‘An extremely un-get-at-able place’ ‘The walks are wonderful’

KEY DATA

KEY DATA

- Terrain: boggy in places, potentially unforgiving weather

- Starting point: Road End (Jura bus from Craighouse); or water taxi to Kinuachdrachd. Sturdy bicycles are also an option for proceeding north from Road End

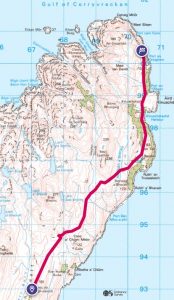

- Distance: 18.2 km (11.4 miles) return

- Walking time: 5 hr 16 mins return

- OS Map: OS Explorer 355. A map can also be found at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10690257/Isle-of-Jura-Argyll-and-Bute-George-Orwell

- Facilities: only in Craighouse

GEORGE ORWELL (1903-1950)

George Orwell lived in a remote farmhouse on the Island of Jura for the last three years of his life from 1946-49. He fell in love with the place and often had visitors with whom he could share walking, fishing and picnic expeditions across the island.

The farmhouse, Barnhill, is as remote as remote can be, seven miles along an unmade-up track, and in exposed country on the northeast of the island. Orwell developed a small holding here, with a fruit and vegetable plot, a chicken coop and at points a few farm animals.

It is where 1984 was written (the last two digits of 1948 reversed), so it has an important place in the annals of Orwellia. The book was going to be called ‘The Last Man in Europe’, which must be how he felt at times living up here!

People are often surprised that such a beautiful spot should be the fertile soil for the dystopia of 1984. But the place enabled Orwell ‘to escape the daily grind of journalism and to find a clean environment which doctors thought would help him recover from a dangerous bout of tuberculosis’. The sheer loneliness and isolation of the place is perhaps the clue to the coldness of the soul that he was able to create in the novel.

THE WALK

Our walk starts from the old quarry at Road End, which is about one km beyond Lealt. As George Orwell forewarned one of his guests: ‘I hope and trust it won’t turn out so, but it might be that you have to walk the last 7 miles. In that case I’ll arrange about the transport of your luggage. But I hope that our van, which is at present hors de combat, will be running again by then. In any case it’s not an unpleasant walk if it isn’t actually pouring.’

Barnhill

Finally coming over a rise, we spot the plain, sizeable whitewashed old farmhouse in a hollow of land with a small field to the front of it. Behind it is the Sound of Jura stretching away towards the hazy coastline of Argyll.

Finally coming over a rise, we spot the plain, sizeable whitewashed old farmhouse in a hollow of land with a small field to the front of it. Behind it is the Sound of Jura stretching away towards the hazy coastline of Argyll.

If you are lucky enough to rent it or come on an organised visit, you will get to see inside, with its Aga, now-faded wall maps of post-war Europe, well-thumbed copies of 1984 and comfortably sagging armchairs. It has barely changed since Orwell lived here.

The bath is a solid cast iron affair with big claw feet and deep stains from the peaty water delivered by the house’s private supply. We stand for a moment imagining the famous author marinating in the bath like a steaming cup of strong tea.

Down the corridor is Orwell’s bedroom. It was here that he completed the manuscript for 1984, sitting in bed, powered by cups of tea, hand-rolled cigarettes and perhaps the occasional mug of gin. The antiquated typewriter is still here and working.

The typical daily activities at Barnhill would be very familiar to any smallholder today. These are some of the items on his to-do list before leaving for the winter in 1947:

- ‘Mend gate, inspect deer fence

- Prepare place for fruit trees

- Lime as much of soil as possible

- Drag up boat

- Grease tools and bring in

- Collect seaweed/leaf mould

- Weight down hen house’

Kinuachdrachd

All we can hear is the trickle of water in the burn alongside the track and birdsong from the trees beyond. We now leave the bleakness behind as the track approaches the verdant wooded oasis around Kinuachdrachd harbour. In the early twentieth century, five families lived here, and a ferry service operated to the mainland until 1932.

Corryvreckan

At the northern tip of the island, we look across the Gulf of Corryvreckan to the smaller island of Scarba.

At the northern tip of the island, we look across the Gulf of Corryvreckan to the smaller island of Scarba.

Corryvreckan comes from the Gaelic Coire Bhreacain meaning ‘cauldron of the speckled seas’. The Corryvreckan whirlpool is reputedly the third largest in the world, created by the flood tide entering the narrow area between the two islands at speeds of up to 16 km/h. As the water flows west it encounters a deep hole and a large pinnacle of basalt rock which generates the infamous whirlpool and standing waves of up to nine metres.

‘Whirlpools and wild places are inextricably linked with our capacity for creativity, as Orwell demonstrated when he chose to come to Jura to write his last novel.’ So wrote Roger Deakin.

In the long hot summer of 1947 Orwell and his family had a closer encounter with the whirlpool than he would have wished.

This is what he wrote in his diary: ‘On return journey today ran into the whirlpool and were nearly all drowned. Engine sucked off by the sea and went to the bottom. Just managed to keep the boat steady with oars and after going through the whirlpool twice, ran into smooth water and found ourselves only about 100 yards from Eilean Mor (a tiny island), so ran in quickly and managed to clamber ashore. We were taken off about three hours later by the Ling fishermen.’

In order to see the whirlpool in action from the shoreline, it is best to time your visit to coincide with a flood tide, preferably backed by a westerly wind. One for the anoraks then.

Supplementary trip to Glengarrisdale Bay

Glengarrisdale Bay can be reached by a 4 by 4 track that comes west off the main track heading north, starting about 1.5 km from Road End. The splendid bay and iconic fisherman’s hut certainly merit a trip.

Orwell wrote in his diary: ‘We had a marvellous summer, six weeks without a drop of rain, and we went for some wonderful picnics on the other side of the island, which is quite uninhabited but where there is an empty shepherd’s cottage (now the Glengarrisdale MBA bothy) one can sleep in. It is a beautiful coast, green water and white sand, and few miles inland lochs full of trout (Loch Doire na h-Achlaise and Loch a’ Gheoidh).’

For many centuries the skull of a Maclean chief slain in battle could be found just above the bothy, but the skull went missing in 1976. Orwell wrote about it: ‘old human skull, with some other bones, lying on beach. Two teeth (back) still in it. Quite undecayed.’ Was it that experience that helped him conjure up the now-famous phrase in 1984: ‘Nothing was your own except the few cubic centimetres inside your skull.’

Across the other side of the bay, we see a slit-like entrance to a sea cave. We enter the cave, which turns out to be a through cave that leads out around a corner.

Across the other side of the bay, we see a slit-like entrance to a sea cave. We enter the cave, which turns out to be a through cave that leads out around a corner.

Beauty and isolation in equal measure, we can see why Orwell loved the place.

Literary Stuff

- Stay at: Barnhill – escapetojura.com/Barnhill.html

- Read: The Collected Non-Fiction: Essays, Articles, Diaries and Letters of George Orwell, 1903-1950

- Read: ‘Waterlog’, by Roger Deakin, which includes a chapter on the whirlpool

- Visit: https://orwellsociety.com/, which runs biennial trips to Barnhill

- Enjoy: The Jura Music Festival, late September each year – https://musicfestival.jurawhisky.com/

- Take A Boat Tour: to the Corryvreckan whirlpool – www.juraboattours.co.uk/tours/corryvreckan/

Leave a Reply