‘If you feel stuck in the clouds in your life and can’t see beyond a certain point, just wait and the clouds will clear.’

‘Belonging is a need like water, air and food.’

‘It was walking through nature that made me feel a sense of belonging and did wonders for my well-being’.

‘I longed for vast open spaces, for cliffs and mountains, to breathe deeply in the great outdoors.’

‘I won’t know for sure if Malhamdale is the finest place there is until I have died and seen heaven (assuming they let me at least have a glance), but until that day comes, it will certainly do.’ Bill Bryson

The Inspiration for this walk: ‘I Belong Here’ (2021)

The first thing that struck me when I read this book is how different it is from the typical nature or walking book, in which the writer is communicating (mansplaining even) their expertise and know-how about the outdoors. For Sethi it is almost the opposite, she is happy to admit that she does not know the name of a bird or that she has bought the wrong walking gear. She speaks as a normal person rather than an outward-bound-y, and that is novel and refreshing.

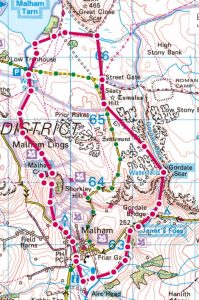

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Rugged, steep climbs, potentially very muddy

- Starting point: Malham village

- Distance: 10.9 km (6.8 miles) return

- Walking time: 3 hrs 12 mins

- OS Map: can be found online athttps://explore.osmaps.com/route/11632037/malham-cove–tarn?lat=54.082732&lon=-2.179765&zoom=12.8531&style=Leisure&type=2d

- Facilities: Pub, toilets, Tourist Information in the village

ANITA SETHI

Anita Sethi is a British journalist and writer, born in Manchester. She wrote ‘I Belong Here: A Journey Along the Backbone of Britain’, in 2021, and it was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize in the Nature Writing category.

It came about after being racially abused on a train journey through the Pennines, including the bigot’s go-to of ‘go back where you belong’. She was traumatised by the experience but decided to fight back by going exactly where she belonged – into the Pennine hills, for an epic walk that helped her explore her reaction to this incident and other horrors of the day, plus questions of identity, culture, colonialism and beauty.

Sethi makes no secret of her novice status as a walker and naturalist, which makes her account of her expedition that much more relatable. City-dwellers are frequently viewed as interlopers in rural areas, dilettantes of the outdoor world. But, despite aching bones and sporadically waterlogged boots, Sethi is undeterred, finding pleasure in everything from picture-postcard waterfalls and ancient gorges to woodland expanses and tiny pockets of moss, all the while intent on completing her walk and reclaiming her right to roam.

The book is a heartfelt examination of identity, place and belonging, and her discovery of greater peace of mind by drawing on the healing powers of nature.

‘As my physical wellbeing improved with every step, so did my mental wellbeing. Walking in nature is good for mental health because it engages all of our senses. It focuses the mind on the external world, the running water, the sound of the birds, the incredible scenery. It made me see that I was part of something bigger than my own worries.’

This sense of ‘I belong here’ has historical echoes through the ages in the friction between the landed gentry, who own the land and use it, and the masses who want access to it, be it, John Clare, in the eighteenth century or the Ramblers’ movement of the twentieth century. Early in the novel, Sethi references the famous Kinder Scout Trespass of 1932, which helped to open up access to the countryside; ‘a way of saying: I belong here.’ And she draws a comparison between her experience and theirs. Nature never judges our humanity, where we come from or where we are going, and in this sense, it is a very benign force.

OUR WALK

We start our walk from the centre of the tiny village of Malham, at the village shop, where we buy chocolate supplies.

The path runs alongside Malham Beck, about which Sethi writes:

The path runs alongside Malham Beck, about which Sethi writes:

‘The sheer force and energy of it swirling there has the effect of washing the mind free from worries; the churning is outside instead of the churning anxiety within. The sound silences noisy thoughts as I instead wonder about the river, how long it has been there, how deep it might be. The swollen river, so strong and sure of itself and its direction, also becomes a subterranean stream somewhere near here at a place called ‘Water Sinks’ (up towards Malham Tarn), and I wonder what it is like, inside the earth.’

Malham Cove

And then she sees Malham Cove ahead, ‘an enormous vertical limestone formation, like a giant cathedral or amphitheatre but made entirely by nature itself rather than any human hand.’

And then she sees Malham Cove ahead, ‘an enormous vertical limestone formation, like a giant cathedral or amphitheatre but made entirely by nature itself rather than any human hand.’

The priest and noted antiquary Thomas West described the Cove in 1779: ‘This beautiful rock is like the age-tinted wall of a prodigious castle; the stone is very white, and from the ledges hang various shrubs and vegetables, which with the tints given it by the bog water. & c. gives it a variety that I never before saw so pleasing in a plain rock.’

Anita continues: ‘Near the cliffs, silvered now by a ray of sun, an abundance of trees grow – old, gnarled and magnificent trees, such an intriguing confluence of elements of the natural world here in sight. A breeze rustles through the trees so they really do sounds as if they are talking to each other.’

We have the same experience as Sethi as we climb: ‘The steps up to the very top – all 400 of them, which look to have been carved from rock and stone – prove to be remarkably steep, and I am soon out of breath. But happy to be fuelled by the supplies I bought from Ronald’s village shop.’

‘We finally reach the end of the steps, which give way to giant, silvery-grey and white-patched rocks, uneven blocks of limestone called clints. It is as if we are stepping onto the surface of the moon.’

Anita walks out onto the Pavement. There is an Information panel at the top of Malham Cove, with words from poet Norman Nicholson:

‘Where flinty clints are scraped bone-bare

A whale’s ribs glint in the sun’

‘We walk further out onto the clints as they spread right to the very edge of the precipice, and I stretch out my arms and savour being so high up and the sweet sense of achievement for having made it there.’

Part of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 1 was filmed around this limestone pavement.

Malham Tarn

Malham Tarn drains at Tarn Foot into a small stream known as Malham Water that soon disappears into the limestone at ‘Water Sinks’, which we pass. The water then reappears not as was originally thought at the base of Malham Cove, but at Airehead Springs.

We return via the spectacular Gordale Scar, which William Wordsworth wrote a poem about in 1819:

Gordale

‘At early dawn, or rather when the air

Glimmers with fading light and shadowy eve

Is busiest to confer and to bereave;

Then, pensive votary! let thy feet repair

To Gordale chasm, terrific as the lair

Where the young lions couch; for so, by leave

Of the propitious hour, thou mayst perceive

The local deity, with oozy hair

And mineral crown, beside his jagged urn

Recumbent: him thou mayst behold, who hides

His lineaments by day, yet there presides,

Teaching the docile waters how to turn,

Or, if need be, impediment to spurn,

And force their passage to the salt-sea tides!’

Janet’s Foss is a small but wonderful waterfall and pool, nestled in a magical wood. The pool was traditionally used for sheep dipping, an event that drew in local village inhabitants for the social occasion. The name Janet is believed to refer to a fairy queen reputed to inhabit a cave at the rear of the fall.

OTHER STUFF

- Check out: local interest books at https://www.malhamdale.com/books/

- Stay: at Malham Bunk Barn, as Anita Sethi did.

- Visit: The Victoria Pub in Kirkby Malham, where Bill Bryson was a regular. He worked in the village for several years and mentions the ‘Malhamdale Wave’ in Notes from a Small Island, the gesture of raising the finger from the steering wheel in recognition when meeting other road users, Bill felt accepted when greeted in this way in the Dale. One of Bill’s favourite views was also in Malhamdale, looking North towards the Cove from the Settle Road out of the village.

Leave a Reply