‘Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote…

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.’

The inspiration for this walk…The Canterbury Tales (1380s)

We really thought we had made it into the world of adulthood and erudition when we started to cart around the ‘Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer’, aka ‘The Doorstop’, in the Lower Sixth, along with wearing a (sober) jacket of our choice. But much as our teacher tried to focus us on the Knight’s Tale, we were intent first on checking out the poker incident in the Miller’s Tale.

Chaucer speaks to us with an irreverence that seems very well suited to today’s times, and he comes across as a ‘man of the people’. Things are not quite what they seem, and people are a lot less godly than they initially come across as.

The only thing that holds back a greater appreciation of Chaucer today is that it is hard to read in the original without extensive research and notes. But it is constantly re-interpreted, most recently (2021) with Zadie’s Smith’s play ‘The Wife of Willesden’, and this I would suggest is the way forward.

This edition is that one I carted around at school when I reached the Lower Sixth, published by Oxford Paperbacks.

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Pavements

- Starting point: Westgate Tower, CT1 2BZ

- Distance: 4.8 km (3 miles); and a short bus ride

- Walking time: 1 hr 16 mins

- OS Map: The route can be found online at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10819548/Canterbury-Kent-Geoffrey-Chaucer

- Facilities: All

GEOFFREY CHAUCER (1340-1400)

Chaucer is widely regarded as the father of modern poetry; and the Canterbury Tales, which he started work on in the 1380s, is his grand oeuvre. It is about a mixed bag of folk embarking on a pilgrimage to Canterbury to pay penance to the relics of Saint Thomas Becket, murdered in the cathedral in 1170. In the centuries that followed, hundreds of thousands of people made the pilgrimage through the Kent countryside to pray at his shrine.

It captures a very different truth about walking, that it can be a very inward-looking activity too; the pilgrims are so busy chatting and telling their tales that they seem almost impervious to their surroundings. There are only a handful of nature/landscape descriptions. The mood of the group is very well captured in William Blake’s beautiful engraving from 1810 by William Blake, `The Canterbury Pilgrims’.

Our walk begins on the outskirts of Canterbury, which you might feel is a little lazy, but practical given that the route Chaucer’s pilgrims would have taken along Watling Street is now largely along the A2 and does not make for pleasant walking.

The Pilgrims’ Way Long Distance Footpath does make a brilliant multi-day walk, but takes another route, from Winchester to Dover, much of the way along the top of the North Downs – it was a favoured route for pilgrims coming from the west. For several hundred years it was largely forgotten, until a specific route was codified by the Ordnance Survey towards the end of the nineteenth century, and this route was popularised by Hilaire Belloc in his book ‘The Old Road’ published in 1904.

OUR WALK

We want to re-trace the route that Chaucer’s pilgrims would have taken into the city, so we start by taking Bus 3 (I know, that doesn’t sound very evocative…), which runs frequently from the bus stop just northeast of Westgate Towers to Harbledown, Hole in the Wall stop at the north end of Church Hill just by the village sign.

Alighting from the bus, we immediately find ourselves on the final stage of the route into Canterbury. Harbledown was the last stop for Chaucer’s pilgrims where, since the cook is too tired or drunk to tell a tale, the Manciple steps forward. His prologue begins:

Woot ye nat where ther stant a litel toun

Which that ycleped is Bobbe-up-and-doun,

Under the Blee, in Caunterbury Weye?

(IX 1-3)

The ‘Bobbe-up-and-doun’ bit very well describes the village street which bobs up and down, and which we are just climbing up now. ‘Under the Blee’ is under Blean Wood, a region of hilly woodland abutting the village which is there to this day (and there I was saying there were few landscape descriptions…)

We start our pilgrimage at the Hospital of St Nicholas (CT2 9AD) on Church Hill, founded by Archbishop Lanfranc in the eleventh century, just opposite the Coach and Horses pub. It is now an Almshouse with a range of cottages for elderly people. Formerly, it was a leper hospital whose inmates supported themselves by displaying a slipper that had been worn by St Thomas Becket; passing pilgrims would leave a donation for the privilege of seeing it, which presumably our pilgrims would have done too.

Walking on through the village we get our first glimpse of Canterbury and the cathedral, rising shimmering and white from the city; and we can only imagine how the pilgrims must have felt on seeing it, a little exhausted (especially the Cook) and elated no doubt in equal measure.

St Dunstan’s Church was the spot where in 1174 Henry II dismounted to begin his walk of penance into Canterbury to atone for his hand in the death of Thomas Becket, the ‘turbulent priest’.

He strode into the church, took off his robes and replaced them with sackcloth. He then walked barefoot down St Dunstan’s Hill and through Westgate to the cathedral, where he submitted himself to a scourging by monks at Becket’s tomb. We take his exact route, still with our boots on though as we are not admitting the need for any personal penance.

The Westgate Gatehouse ahead is the largest surviving city gate in England. Dating back to around 1379, it would have been shiny new in Chaucer’s day. Given that at one time he was Clerk of Works with responsibility for Canterbury’s defences, he would no doubt have taken a keen interest in it.

The Westgate Gatehouse ahead is the largest surviving city gate in England. Dating back to around 1379, it would have been shiny new in Chaucer’s day. Given that at one time he was Clerk of Works with responsibility for Canterbury’s defences, he would no doubt have taken a keen interest in it.

Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) was born and raised in Canterbury and The Marlowe Theatre, rebuilt in 2011, commemorates him. In front of the present theatre, we admire a nineteenth-century statue, The Muse of Poetry, surrounded by small effigies of characters from Marlowe’s plays: Tamburlaine, Dr Faustus, Barabas and Edward II.

Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) was born and raised in Canterbury and The Marlowe Theatre, rebuilt in 2011, commemorates him. In front of the present theatre, we admire a nineteenth-century statue, The Muse of Poetry, surrounded by small effigies of characters from Marlowe’s plays: Tamburlaine, Dr Faustus, Barabas and Edward II.

A larger-than-life statue of Geoffrey Chaucer, dressed as a Canterbury pilgrim, stands on the corner of Best Lane and the High Street. Chaucer faces the Eastbridge Hospital, where many pilgrims heading for the cathedral spent the night.

Chaucer’s pilgrims may well have dropped their possessions off at the Checker of the Hope Inn, before proceeding to penance, as recorded in the fifteenth-century text the ‘Tale of Beryn’:

‘They toke her In, & loggit hem at mydmorowe, I trowe,

Atte ‘Cheker of the Hope,’ that many a man doith knowe.’

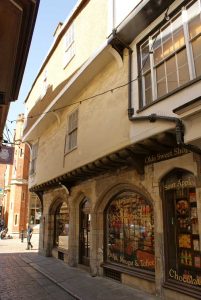

It is at the bottom of Mercery St, and its overall structure we can still see as we pass by today, especially the arcaded ground floor. The Chequers was a large inn with a courtyard. On the ground floor were shops selling all manner of goods; richer pilgrims took suites on the first floor, overlooking the grand courtyard where players acted for their entertainment; whilst poorer pilgrims were squashed into dormitories on the top floor.

It is at the bottom of Mercery St, and its overall structure we can still see as we pass by today, especially the arcaded ground floor. The Chequers was a large inn with a courtyard. On the ground floor were shops selling all manner of goods; richer pilgrims took suites on the first floor, overlooking the grand courtyard where players acted for their entertainment; whilst poorer pilgrims were squashed into dormitories on the top floor.

It may very well have been the spot where having paid penance at the cathedral, Chaucer’s pilgrims broke their fast and met to decide who had told the best tale. Before the pilgrims set off, the Host had announced a competition: the pilgrim who told his tale with ‘best sentence and moost solaas’ (instruction and delight) would receive a free meal. We can imagine that merry band eating and carousing late into the night under these arcades. Nowhere though is it recorded which tale was judged to be the best…

Canterbury Cathedral

In Chaucer’s day, there would have been shops selling badges and souvenirs for pilgrims to buy in the cathedral precinct, and often there were fairs and other entertainments.

In Chaucer’s day, there would have been shops selling badges and souvenirs for pilgrims to buy in the cathedral precinct, and often there were fairs and other entertainments.

‘Than, as manere & custom is, signes there they bougte,

ffor men of contre shuld know whom they had ougte

Ech man set his silvir in such thing as they likid.’ The Tale of Beryn

On entering the cathedral through the southwest door of the nave, the pilgrims would have been blessed with holy water by a priest. They would then have made their way to the main shrine of St Thomas Becket in the Trinity Chapel at the east end, prayed and given their offering here and then afterwards visited some of the many other shrines, relics, holy images, and altars in the cathedral. As far as is possible we follow this very same route.

The Martyrdom Chapel was the site of Becket’s murder, the spot where he lay dying from the wounds gorily described by a watching monk, Edward Grim. Here there was a small altar that had a reliquary containing the point of the sword which had cut into his head. The flagstones were said to bear the marks of his final footprints, and pilgrims came to kiss them.

The Martyrdom Chapel was the site of Becket’s murder, the spot where he lay dying from the wounds gorily described by a watching monk, Edward Grim. Here there was a small altar that had a reliquary containing the point of the sword which had cut into his head. The flagstones were said to bear the marks of his final footprints, and pilgrims came to kiss them.

Becket’s last moments were brought to life again in TS Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral, first performed in the Chapter House in June 1935:

‘We come for the King’s justice, we come with swords,’ the first knight finally declares. Becket holds his ground: ‘It is not I who insult the King/And there is higher than I or the King.’ And it is clear that he is not afraid of his impending death: ‘I am not in danger: only near to death.’ He is then struck down.

King’s School, Canterbury

When he was fourteen, Marlowe became a King’s Scholar, one of ‘fifty boys both destitute of the help of friends and endowed with minds apt for learning’. Pupils were expected to speak in Latin at all times, even when playing.

Somerset Maughan (1874-1965) described his unhappy time at this school in ‘Of Human Bondage’, but became much more fond of the place as he grew older, bequeathing money and books. His ashes were scattered in a garden in the school. A small commemorative plaque marks the event.

Hugh Walpole also went to the school, as did Michel Morpurgo, the children’s writer, and the travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, who described it thus:

‘There was a wonderfully cobwebbed feeling about this dizzy and intoxicating antiquity – an ambiance both haughty and obscure which turned famous seats of learning, founded eight hundred or a thousand years later, into gaudy mushrooms and seemed to invest these hoarier precincts, together with the wide green expanses beyond them, the huge elms, the Dark Entry, and the ruined arches and the cloisters – and, while I was about it, the booming and jackdaw-crowed pinnacles of the great Angevin cathedral itself, and the ghost of St. Thomas à Becket and the Black Prince’s bones – with an aura of nearly pre-historic myth.’

Something about the place seems to have nurtured literary endeavour.

As we walk out of the school into Palace St, we start to see some of Charles Dickens’ links with the city. His favourite novel ‘David Copperfield’ (1849) was set here, and he knew the place well, being a frequent visitor. Dickens gave a reading from David Copperfield at the new Theatre Royal in 1861. Along with Chaucer, he is one of the great storytellers of our literary history. Not surprising really that he borrowed one of Chaucer’s plots (from The Merchant’s Tale) for his third Christmas book, ‘The Cricket on the Hearth’.

David Copperfield was educated in the city, and much of Dickens’ description of ‘Dr Strong’s Academy’ suggests that it was modelled on King’s School.

At the top of Palace St, we spot one of Canterbury’s most photographed buildings, the ‘Crooked House’, featuring a Charles Dickens quote above the door. ‘…a very old house bulging out over the road; a house with long low lattice-windows bulging out still farther, and beams with carved heads on the ends bulging out too, so that I fancied the whole house was leaning forward…’

Next, on our right, we see the ancient St Alphege Church, where Dr Strong and Annie Markleham were married.

As we reach the bottom of Palace St, we come to The Sun Hotel (8 Sun Street), where Charles Dickens used to stay during his visits to Canterbury. ‘It was a little inn where Mr Micawber put up, and he occupied a little room in it, partitioned off from the commercial room…’

The Butter Market at Christ Church Gate is also mentioned in David Copperfield: ‘We came to Canterbury, where, as it was market-day, my aunt had a great opportunity of insinuating the grey pony among carts, baskets, vegetables, and huckster’s goods.’ It still bustles as we pass through it today.

Finally, we move into Christopher Marlowe territory. We pass the clock tower of St George the Martyr (the rest of the church was destroyed) where he was baptised in February 1564. His childhood home was at 14 St George’s St, now the site of Fenwicks Store.

Finally, we move into Christopher Marlowe territory. We pass the clock tower of St George the Martyr (the rest of the church was destroyed) where he was baptised in February 1564. His childhood home was at 14 St George’s St, now the site of Fenwicks Store.

The rest of the walk takes us to quieter and very charming parts of the city. We pass the Dane John Mound, formerly a Roman cemetery and subsequently a Norman castle; and Greyfriars Chapel, the first Franciscan friary in England, dating back to 1267. Both spots are very peaceful places to take a break from the bustle of the city centre. Finally, we pop into the very informative Marlowe Kit (see below) towards the end of the walk.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: The Beaney House of Art & Knowledge, 18 High St, CT1 2BD (01227 862162, https://canterburymuseums.co.uk/beaney/ ), includes examples of pilgrim badges and necklace phials used for carrying supposed dilutions of Becket’s blood – both are mentioned in the Tales. There is also a Rupert Bear exhibition. Its original creator, Mary Tourtel, lived in Canterbury all her life. There is a plaque in 63 Ivy Lane (CT1 1TU) marking the place where Tourtel spent her final years.

- Climb: Westgate Towers (CT1 2BZ) for a spectacular view of this fine city

- Visit: The Kent’s Remarkable Writers: Exhibition at the Marlowe Kit, Poor Priests’ Hospital, Stour St, CT1 2NZ (01227 787787). The exhibition is focused on three writers who had strong connections with the city; Christopher Marlowe, Aphra Behn (born in Harbledown in 1640) and Joseph Conrad.

- Browse: The Chaucer Bookshop, 6-7 Beer Cart Lane, CT1 2NY. The best second-hand bookshop in the city is full of rare and out-of-print books.

- Visit: The grave of Joseph Conrad (1857-1924): buried at Canterbury City Cemetery (9 Becket Ave, CT2 8JN) near the start of the walk. Conrad spent the final five years of his life in Bishopsbourne, just outside Canterbury.

- Attend: The Canterbury Festival (https://canterburyfestival.co.uk/), held in October each year, hosting performances of theatre, music, poetry readings, talks from authors, stand-up comedy and walks around the historic city.

Visit:

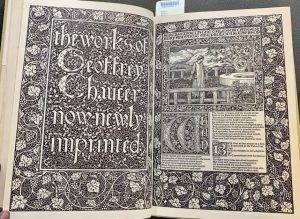

the glorious Arts & Crafts Red House, Bexleyheath (DA6 8JF), William Morris’s first home and just a short way off Watling Street, the route of the pilgrims. William Morris was a fan of medievalism and Chaucer. In reference to the route, Morris termed the passage which connects the main hallway to the house’s rear entrance, ‘The Pilgrim’s Rest”‘ It has some lovely glass window panes with images of Chaucer’s poem the ‘Parlement of Foules’ on them. The Kelmscott Chaucer that he created towards the end of his life is the most memorable and beautiful edition of the complete works of Chaucer ever produced.

the glorious Arts & Crafts Red House, Bexleyheath (DA6 8JF), William Morris’s first home and just a short way off Watling Street, the route of the pilgrims. William Morris was a fan of medievalism and Chaucer. In reference to the route, Morris termed the passage which connects the main hallway to the house’s rear entrance, ‘The Pilgrim’s Rest”‘ It has some lovely glass window panes with images of Chaucer’s poem the ‘Parlement of Foules’ on them. The Kelmscott Chaucer that he created towards the end of his life is the most memorable and beautiful edition of the complete works of Chaucer ever produced.

Leave a Reply