‘See what I can do!

The Inspiration for this walk: ’Brick Lane’

I read this book when it first came out in paperback in 2004, I remember at the time that everyone was talking about it. And Brick Lane itself was starting to become a ‘go to’ street.

Now some say the book has not aged well, but I still love it. The themes are ones we can all relate to – arriving somewhere totally unfamiliar, adapting to a new culture in fits and starts; and finally assimilating or ‘belonging’. In that sense it is in the classic tradition of the English novel.

As Monica Ali put it: ‘The central issue for Nazneen is, “What is it in my life that I can control and what must be accepted?” For her, everything is framed in terms of her own particular social, cultural, religious and family background. She has very different terms of reference to the average Westerner, but the issues are universal.’

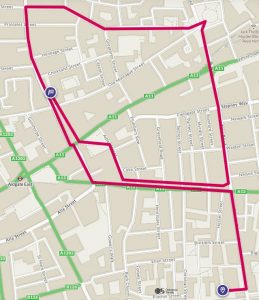

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Twisty route in keeping with Nazneen’s own peregrinations

- Starting point: Aldgate East Tube to Whitechapel

- Distance:5 kms (2.2 miles)

- Walking time: 50 mins

- OS Map: https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/11222673/-Brick-Lane-East-End-London-Monica-Ali

- Facilities: pubs, cafés

MONICA ALI (1967-

Monica Ali was born in Dhaka, East Pakistan, in 1967 to a Bengali father and an English mother. During the civil war that led to the creation of Bangladesh, the family moved to England, where they settled in the north.

Brick Lane is a street at the heart of London’s Bangladeshi community. Ali’s 2003 novel follows the life of Nazneen, a Bangladeshi woman who moves to London at the age of 18, to marry an older man, Chanu. At first her English consists only of ‘sorry’ and ‘thank you’. The novel explores her development, including her illicit relationship with Karim. By the end of the novel Nazneen has finally settled into her new life and taken control of her space and relationships.

If you are looking for writing that evokes the character and flavours of Brick Lane, you will not find it here. In fact, Ali had wanted to call it ‘Seven Seas and Thirteen Rivers’, but her publishers suggested Brick Lane would be more catchy. But the symbolism of Brick lane is important – it has a rich migrant heritage dating from the French Huguenots and encompassing the Irish, the Jews and more recently the Bangladeshis. It is what Brick Lane represents rather than the place itself that is important. It provides an obvious physical contrast between her youth (a pastoral idyll) and her new life (the unwelcoming city):

If you are looking for writing that evokes the character and flavours of Brick Lane, you will not find it here. In fact, Ali had wanted to call it ‘Seven Seas and Thirteen Rivers’, but her publishers suggested Brick Lane would be more catchy. But the symbolism of Brick lane is important – it has a rich migrant heritage dating from the French Huguenots and encompassing the Irish, the Jews and more recently the Bangladeshis. It is what Brick Lane represents rather than the place itself that is important. It provides an obvious physical contrast between her youth (a pastoral idyll) and her new life (the unwelcoming city):

‘You can spread your soul over a paddy field, you can whisper to a mango tree, you can feel the earth between your toes and know that this is the place, the place where it begins and ends. But what can you tell to a pile of bricks? The bricks will not be moved.’

The symbolism of space is very important to her journey of self-realisation throughout the novel – the freedom of the paddy fields of her childhood, the initial ‘imprisonment’ in her flat that then becomes her haven, the intimidating unfamiliarity of Brick Lane itself; and then the increasing willingness to move freely into spaces, from long walks in the vicinity to a willingness to go solo to a meeting of the Bengal Tigers where men and women mix and radical ideas are shared; and eventually ending in searching for someone else (her daughter) and confronting a policeman.

Our walk attempts to follow this journey of self-realisation.

OUR WALK

Let’s start our walk at the sort of estate that Chanu & Nazneen lived in. The estate that perhaps closest fits the description is Walford House, just west of Cannon St Rd and just to the north of the railway lines.

These are the clues that seem to match: ‘The flats closed three sides of a square’…the tattoo lady lives on the fourth floor (four stories altogether); ‘She walked along the corridor looking at the front doors. They were all the same…a rectangular panel of glass with wire meshing suspended inside’; ‘She watched him (Chanu) from the window as he stepped like a band leader across the courtyard to the bus top on the far side of the estate.’ (Cannon St Rd); ‘In the summer they stood outside next to the big metal bins’

These are the clues that seem to match: ‘The flats closed three sides of a square’…the tattoo lady lives on the fourth floor (four stories altogether); ‘She walked along the corridor looking at the front doors. They were all the same…a rectangular panel of glass with wire meshing suspended inside’; ‘She watched him (Chanu) from the window as he stepped like a band leader across the courtyard to the bus top on the far side of the estate.’ (Cannon St Rd); ‘In the summer they stood outside next to the big metal bins’ ; ‘At sixteen floors up, if you decide to jump, then there’s the end of it’ (Luke House in nearby Bigland St well fits the description, 22 blocks high).

; ‘At sixteen floors up, if you decide to jump, then there’s the end of it’ (Luke House in nearby Bigland St well fits the description, 22 blocks high).

To begin with, Nazneen ‘did not often go out’. She ‘sometimes thought of going downstairs, crossing the yard…she thought of it, but she would not go.’

The first change in Nazneen’ s self occurs when, overwhelmed by bad news from her sister in Bangladesh, she ventures out of the flat by herself for almost the first time:

‘At the main road (Commercial Rd) she looked both ways and then went left…she walked until she reached the big crossroads…Twice she stepped into the road and drew back again. To get to the other side of the street without being hit by a car was like walking out in the monsoon and hoping to dodge the raindrops. A space opened up before her. God is great, said Nazneen under her breath. She ran. A horn blared like an ancient muezzin ululating painfully, stretching his vocal cords to the limit. She stopped and the car swerved. Another car skidded to a halt in front of her and the driver got out and began to shout. She ran again and turned into a side street, then off again to the right onto Brick Lane.

‘Brick Lane was deserted, (you are very unlikely to find that to be the case!) Nazneen stopped by some film posters pasted in waves over a metal siding…she walked to the end of Brick Lane and turned right.’

We follow, taking a right down Hanbury St, famous for its street art adorning every available wall. The streets around Brick Lane have a regular display of graffiti, which features artists such as Banksy, Stik, ROA, D*Face, Ben Eine and Omar Hassan

We follow, taking a right down Hanbury St, famous for its street art adorning every available wall. The streets around Brick Lane have a regular display of graffiti, which features artists such as Banksy, Stik, ROA, D*Face, Ben Eine and Omar Hassan

From this point, Nazneen’s walk seems to very much adopt the style of a pyschogeographer in its aimlessness: ‘From there she took every second right and every second left until she realised she was leaving herself a trail. Then she turned off at random…’ Monica Ali describes herself as ‘a keen walker’, so I have no doubt there is a bit of her in there, and that she too took this walk whilst researching the novel.

Nazneen is experiencing exactly the anonymity of the street that Virginia Woolf describes in ‘Night Haunting’ – ‘As we step out of the house…we shed the self’. Ali puts it like this; ‘But they were not aware of her…they could see that she existed but unless she did something, waved a gun, halted the traffic, they would not see her. She enjoyed that thought.’ Growing empowerment.

At the end of Hanbury St we arrive in Vallance Gardens, a public space that could easily be the one described in this passage:

‘There was a patch of green surrounded by black railings, and in the middle two wooden benches. In this city, a bit of grass was something to be guarded, fenced about, as if there were a sprinkling of emeralds sown in among the blades. Nazneen found the gate and sat alone on the bench. A maharanee in her enclosure. The sun came out from behind a black cloud and shone briefly in her eyes before plunging back under cover, disappointed with what it had seen.’

‘A young man, tall as a stilt-walker and with the same stiff-kegged gait, came and sat on the opposite bench. He put his motorcycle helmet on the ground. He ate a sandwich in four large bites.’

Nazneen is beginning to experience a kind of epiphany and realizes other possibilities for herself.

‘She began to feel a little pleased. She had spoken, in English, to a stranger, and she had been understood and acknowledged. It was very little, but it was something.’

‘Anything is possible …. Do you know what I did today? I went inside a pub. To use the toilet. Did you think I could do that? I walked mile upon mile, probably around the whole of London, although I did not see the edge of it. And to get home again I went to a restaurant. I found a Bangladeshi restaurant and asked directions. See what I can do!’

From here we head back down to Commercial Rd, turn right and then follow Nazneen’s final journey in the book inn search of her daughter, by which time she has reached a much higher state of self-empowerment:

‘Out of the estate and onto Commercial Road, past the clothes wholesalers, up Adler Street and left onto the brief green respite of Altab Ali Park where the neat, pale-faced block of flats had picture windows and a gated entrance, from which the City boys could stroll to work. Nazneen ran down the slope and caught the green man at the crossing on Whitechapel.

‘Out of the estate and onto Commercial Road, past the clothes wholesalers, up Adler Street and left onto the brief green respite of Altab Ali Park where the neat, pale-faced block of flats had picture windows and a gated entrance, from which the City boys could stroll to work. Nazneen ran down the slope and caught the green man at the crossing on Whitechapel.

‘A row of police vans covered the mouth of Brick Lane. Behind them a legion of policemen stood with arms folded and feet turned out. A length of tangerine-and-white-striped tape stuck the sides of the street together.

‘Let me through,’ said Nazneen.

‘The street is closed, madam. Go back.’ The policeman sounded friendly but decisive. He seemed to think the conversation was finished.

‘I have to go to Shalimar Cafe and find my daughter.’

‘Why I can’t go through?’ said Nazneen. She put her face right up to the policeman’s face. Do you see me now? Do you hear me?’

Nazneen has truly arrived, as we have at the end of our journey.

We finish by admiring the archway at the mouth of Brick Lane. Designed by Meena Thakor, it was erected in 1997 to mark the entrance to ‘Banglatown’, the name coming from a marketing campaign to celebrate all things Bangladeshi in Brick Lane, especially its restaurants and annual street festivals. The novel Brick Lane, published five years later, benefited greatly from this association but is also much greater than that.

We finish by admiring the archway at the mouth of Brick Lane. Designed by Meena Thakor, it was erected in 1997 to mark the entrance to ‘Banglatown’, the name coming from a marketing campaign to celebrate all things Bangladeshi in Brick Lane, especially its restaurants and annual street festivals. The novel Brick Lane, published five years later, benefited greatly from this association but is also much greater than that.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: The Whitechapel Gallery

- Visit: https://inspiringcity.com/2020/01/21/where-to-find-street-art-and-graffiti-on-brick-lane/#h-map-of-street-art-on-brick-lane for a good introduction to the street art

- Watch: the film ‘Brick Lane’ (2007)

- Go on: A Brick Lane and Shoreditch Bookshops Tour

- Read: ‘Salaam Brick Lane’ by Tarquin Hall, ‘On Brick Lane’ (2007) by Rachel Lichtenstein

Enjoy: The Brick Lane Bookshop, 166 Brick Lane, E1 6RU

Enjoy: The Brick Lane Bookshop, 166 Brick Lane, E1 6RU- Book a place: on Lady’s Self-Guided Street Art Tour of London: https://www.aladyinlondon.com/2019/06/street-art-tour-london.html

Leave a Reply