‘Upon smooth Quantock’s airy ridge we roved, unchecked, or loitered ’mid her sylvan combes’ (Wordsworth)

‘Now, my friends emerge

Beneath the wide wide Heaven—and view again

The many-steepled tract magnificent

Of hilly fields and meadows, and the sea’ (Coleridge)

The inspiration for this walk…The Lyrical Ballads (1798)

When I first started to study English Literature at university my natural tendency was to look for rules and codifications…is there a considered objective correlative here, should the narrator be visible in the text, what makes a great poem etc. etc. – so the Preface to The Lyrical Ballads was nirvana to me, explaining (in rather pedantic detail) what made a great poem – most famously the phrase ’emotion recollected in tranquiliity’.

We then just added the label ‘The Official Birth of Romantic Poetry’ and the job seemed to be done. That is, at least, until we started to read other poetry, and then also delve deeper into the complex actual dynamic between Wordsworth, Coleridge and Dorothy Wordsworth. Now, years later, I realise that nothing is ever as simple as it seems..and none the worse for that.

This edition is the one I bought in my first year of university study.

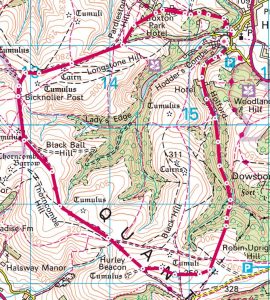

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Hills, steep ascents and descents

- Starting point: Holford Village Green, TA5 1SB

- Distance: 10.2 km (6.4 miles)

- Walking time: 3 hrs 3 mins

- OS Map: OS Explorer 140. The map can be found online at: https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/8064812/Quantocks-Coleridge-Wordsworth

- Facilities: Plough Inn in Holford

WORDSWORTH (1770-1850) & COLERIDGE (1772-1834)

The Quantock Hills are of enormous literary significance. In 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth lived here for a year when they were both in their mid-twenties. Walking up the combes and over the hills inspired them to create a new language of romanticism and some of the greatest poems ever written.

Coleridge Cottage

Coleridge moved to a small cottage in Nether Stowey at the invitation of his patron Thomas Poole, who lived nearby and wanted to help the impecunious writer. This gave Coleridge a fresh start and, to begin with at least, he was determined to keep to a strict schedule of writing:

Coleridge moved to a small cottage in Nether Stowey at the invitation of his patron Thomas Poole, who lived nearby and wanted to help the impecunious writer. This gave Coleridge a fresh start and, to begin with at least, he was determined to keep to a strict schedule of writing:

‘From seven to half past eight I work in my garden; from breakfast till 12 I read & compose; then work again – feed the pigs, poultry &c. till two o’clock – after dinner work again till Tea – from Tea till supper review. So jogs the day; & I’m happy.

Coleridge and Wordsworth meet and join up

Coleridge and Wordsworth corresponded for several years before actually meeting. When they did finally meet, their rapport was instantaneous, as Coleridge recalls:

‘I had been on a visit to Wordsworth’s at Racedown near Crewkherne – and I brought him & his Sister back with me & here I have settled them (in Alfoxton Hall).’

‘The park and woods are his for all purposes he wants them – i.e. he may walk, ride, & keep a horse in them – & the large gardens are altogether & entirely his. Wordsworth is a very great man – the only man, to whom at all times & in all modes of excellence I feel myself inferior.’

Coleridge and the Wordsworths formed an especially tight bond, ‘Three people, but one soul’ in Coleridge’s words. Dorothy described a moment of their togetherness like this: ‘We lay sidelong upon the turf, and gazed on the landscape till it melted into more than natural loveliness.’

At the heart of their relationship lay walking. They walked pretty much every day, and often long distances. This is Dorothy’s journal entry for the month of February 1978:

4 February. Walked a great part of the way to Stowey with Coleridge.

5 February. Walked to Stowey with Coleridge, returned by Woodlands.

6 February. Walked to Stowey over the hills.

22 February. Coleridge came in the morning to dinner.

23 February. William walked with Coleridge in the morning.

When Coleridge famously couldn’t go walking with his mates, we hear about that too in his poem ‘This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison’:

‘Well, they are gone, and here must I remain,

This lime-tree bower my prison!’

They often set off in the early evening as the day was fading and the enveloping and enlarging beauties of the Quantocks started to reveal themselves. They took with them their notebooks and pens, their spyglasses and folding camp stools, with portfolios of paper in which to record what they saw. ‘Voluptuous’ walking was precisely the purpose of these Quantock walks, a chance to think at liberty and without constraint:

‘better far than this to stray about

Voluptuously through fields and rural walks

And ask no record of the hours given up.’

Wordsworth, The Prelude

William Hazlitt, a friend of both of them, recorded that Coleridge was in the habit of walking in a zig-zag fashion in front of his companion, ‘unable to keep on in a straight line’ while endlessly, brilliantly, talking. Unlike William Wordsworth, who liked to walk backwards and forwards along a flat path, muttering to himself as he composed his verses, Coleridge preferred composing his verses while on uneven ground, ‘or breaking through the straggling branches of a copse-wood’, terrain he considered more likely than a smooth, uninterrupted surface to foster the making of poetry. This difference in walking style perfectly reflects the poetic differences between them too, Wordsworth’s poetry rooted in the every day, whilst Coleridge’s is given to flights of fancy, spurred on no doubt by his opium habit. What they both had in common was their love of and belief in the power of nature.

THE WALK

The bridge at Holford

We start by crossing the bridge over the Holford Coombe, the prominent geographic feature of our walk, a powerful stream that in many places has cut a ravine through the landscape. This bridge and stream are described by Coleridge in his poem ‘The Nightingale’ (1798), which starts:

‘No cloud, no relique of the sunken day

Distinguishes the West, no long thin slip

Of sullen light, no obscure trembling hues.

Come, we will rest on this old mossy bridge!

You see the glimmer of the stream beneath,

But hear no murmuring: it flows silently.

O’er its soft bed of verdure. All is still.

A balmy night! and though the stars be dim,

Yet let us think upon the vernal showers

That gladden the green earth, and we shall find

A pleasure in the dimness of the stars.

And hark! the Nightingale begins its song,

‘Most musical, most melancholy’ bird!’

Dorothy’s Glen

We turn left here along the road after the bridge and cross back over the stream again by a footbridge. Downstream from here is the spot called Dorothy’s Glen, which she describes in her diaries:

We turn left here along the road after the bridge and cross back over the stream again by a footbridge. Downstream from here is the spot called Dorothy’s Glen, which she describes in her diaries:

‘There is everything here; sea, woods, wild as fancy ever painted, brooks clearly and pebbly…villages so romantic; and William and I, in a wander by ourselves, found out a sequestered waterfall in a dell formed by steep hills covered with full-grown timber trees.’

In his poem ‘This Lime-tree Bower My Prison’ the house-bound Coleridge imagines his friends visiting this spot:

‘The roaring dell, o’erwooded, narrow, deep,

And only speckled by the mid-day sun;

Where its slim trunk the ash from rock to rock

Flings arching like a bridge;- that branchless ash,

Unsunn’d and damp, whose few poor yellow leaves

Ne’er tremble in the gale, yet tremble still,

Fann’d by the water-fall!’

And William Wordsworth wrote his poem ‘Lines Written in Early Spring’ here too, which opens:

‘I heard a thousand blended notes,

While in a grove I sate reclined,

In that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts

Bring sad thoughts to the mind.’

This spot became for them a potent symbol of the inspirational power of nature. Unfortunately, we can’t see the waterfall from this footbridge, but we can certainly hear it just downstream. It’s a surprisingly impressive falls, William Wordsworth describing it as ‘considerable for that country’.

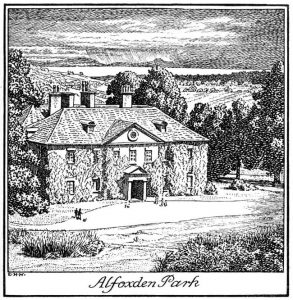

Alfoxton Park

We cli mb up along the Coleridge Way out of the woods and emerge in Alfoxton Park.

mb up along the Coleridge Way out of the woods and emerge in Alfoxton Park.

William Hazlitt describes a typical scene there:

‘That morning, as soon as breakfast was over, we strolled out into the park, and seating ourselves on the trunk of an old ash-tree that stretched along the ground, Coleridge read aloud with a sonorous and musical voice (his poems) …

…and the sense of a new style and a new spirit in poetry came over me. It had to me something of the effect that arises from the turning up of the fresh soil, or of the first welcome breath of Spring.’

Alfoxton (Alfoxden) Hall

Although considerably extended since their day, this was the very house that the Wordsworths rented for a year to be close to Coleridge.

This is where the two poets created their joint masterpiece, ‘The Lyrical Ballads’. Coleridge first read ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ to his friends here in the oak-panelled room, on the right as you look at the front of the house.

Dorothy beautifully evokes the house and surrounding landscape in her Alfoxden Journal, which regularly provided ideas and inspirations for Wordsworth’s poetry (‘she gave me eyes, she gave me ears’):

‘Here we are in a large mansion, in a large park with seventy head of deer around us. There is furniture enough for a dozen families like ours. There is an excellent garden, well stocked with vegetables and fruit. The front of the house is to the south, but it is screened from the sun by a high hill. From the end of the house we have a view of the sea.’ (her favourite writing spot was on the northeast end of the house).

‘Walked upon the hill-tops; followed the sheep tracks till we overlooked the larger coombe. Sat in the sunshine. The distant sheepbells, the sound of the stream; the woodman winding along the half-marked road with his laden pony; locks of wool still spangled with the dewdrops; the blue-grey sea, shaded with immense masses of cloud, not streaked; the sheep glittering in the sunshine.’

‘The sound of the sea distinctly heard on the tops of the hills, which we could never hear in summer. We attribute this partly to the bareness of the trees, but chiefly to the absence of the singing of birds, the hum of insects, that noiseless noise which lives in the summer air. The villages marked out by beautiful beds of smoke. The turf fading into the mountain road. The scarlet flowers of the moss.’

Alfoxden is now a Buddhist Eco Retreat Centre, perhaps the embodiment of ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’. Dorothy would definitely approve that they are keen on gaining self-sufficiency in fruit and veg from the walled garden again, where she and William loved to walk and often sat to write.

Bicknoller Post

Dorothy wrote in her diary: ‘Wm. and I walked to the hill-tops, a very cold bleak day. We were met on our return by a severe hailstorm. William wrote some lines describing a stunted thorn’…and on another occasion ‘Came home …by the thorn, and the ‘little muddy pond’.

We can still spot the thorn and the muddy pond today, the inspiration for Wordsworth’s poem ‘The Thorn’:

‘High on a mountain’s highest ridge,

Where oft the stormy winter gale

Cuts like a scythe, while through the clouds

It sweeps from vale to vale;

Not five yards from the mountain path,

This Thorn you on your left espy;

And to the left, three yards beyond,

You see a little muddy pond

Of water – never dry,

Though but of compass small, and bare

To thirsty suns and parching air.’

Black Hill

Here, near the round summit of Black Hill, on Pack Way, is a fine example of the sweeping panoramic vistas for which the Quantocks have become celebrated. The grey-brown Bristol Channel spreads out to the north, dotted with the islands of Flat Holm and Steep Holm.

Today we are lucky enough to see the Brecon Beacons on the Welsh side. This is exactly the sort of spot that Wordsworth had in mind when he recalled roving around on ‘smooth Quantocks airy ridge’.

Frog Hill

In the autumn of 1797, Coleridge was working on a poem that he called The Brook, though he never completed it. It is Holford Combe brook that he has in mind; and its source, Wilmot’s Pool is where we are now.

Coleridge describes his thinking:

‘I sought for a subject, that should give equal room and freedom for description, incident, and impassioned reflections on men, nature, and society, yet supply in itself a natural connection to the parts, and unity to the whole. Such a subject I conceived myself to have found in a stream, traced from its source in the hills among the yellow-red moss and conical glass-shaped tufts of Bent, to the first break or fall, where its drops became audible, and it begins to form a channel; thence to the peat and turf barn, itself built of the same dark squares as it sheltered; to the sheep-fold; to the first cultivated plot of ground; to the lonely cottage and its bleak garden won from the heath; to the hamlet, the villages, the market-town, the manufactories, and the sea-port. My walks therefore were almost daily on the top of Quantock, and among its sloping coombs. With my pencil and memorandum book in my hand, I was making studies, as the artists call them, and often moulding my thoughts into verse, with the objects and imagery immediately before my senses.’

Here are a few of the fragments:

‘On the broad mountain-top

The neighing wild-colt races with the wind

O’er fern & heath-flowers-‘

I especially like this one, describing Holford Mill when it is still:

‘Sabbath day – from the

Miller’s mossy wheel

the waterdrops dripp’d

leisurely – ‘

..and as we come back into Holford itself:

‘A long deep Lane

So overshadow’d, it might seem one bower—

The damp Clay banks were furr’d with mouldy moss’

So, although the poem is only partially completed, our journey down the brook is now complete. What a fabulous journey.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: Coleridge’s Cottage at Nether Stowey (National Trust)

- Walk: The Coleridge Way, a 51-mile (82 km) footpath, linking several sites associated with the poet. See https://www.visit-exmoor.co.uk/coleridge-way/coleridge-way-home-page

- Read: Dorothy Wordsworth’s Alfoxden Journal at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42856/42856-h/42856-h.htm

- Read: ‘The Making of Poetry – Coleridge, the Wordsworths and their Year of Marvels’, by Adam Nicholson (2019)

- Read: Alice Oswald’s ‘Dart’ (2002) for a completed poem about a river’s journey from source to sea. Also, Nan Shepherd’s ‘Living Mountain’, reflections on the River Dee from its source to sea: ‘As I stand in the silence, I realise the silence is not complete. Water is speaking.’

- Watch: ‘Pandaemonium’ (2001), a film about the relationship between Coleridge, Dorothy and William Wordsworth, filmed on location in the Quantocks.

- Imbibe: at The Plough Inn in Holford (TA5 1RY). Virginia and Leonard Woolf spent their honeymoon here in 1912 and would undoubtedly have taken many of the same paths as us as they were keen walkers. Virginia wrote of her stay ‘Divine country, literary associations, cream for every meal’.

- Stay: at The Old Cider House in Nether Stowey, very walker-friendly and knowledgeable hosts: http://www.theoldciderhouse.co.uk/

Leave a Reply