‘Oh Sylvan Wye! Thou wanderer through the woods, How often has my spirit turned to thee!’

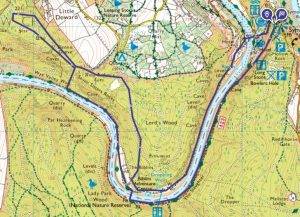

KEY DATA

- Terrain: muddy, steep climbs

- Starting point: Symonds Yat Rock Car Park, GL12 7NZ

- Distance: 9.6 km (5.9 miles)

- Walking time: 3 hrs

- OS Map: OS Explorer OL14 Wye Valley and the Forest of Dean. This route can be found online at: https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/9585759/Symonds-Yat-above-Tintern-Abbey-Herefordshire-William-Wordsworth

- Facilities: Pub at Symonds Yat East, the Saracen’s Head Inn

- Check: The chain ferry is open and working.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH (1770-1850)

First of all, we need to give Wordsworth’s most famous poem its full title: ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798’. The title is often abbreviated simply to Tintern Abbey, which is very confusing as the abbey does not appear anywhere in the poem.

William Wordsworth first visited the Wye Valley as a young man in 1793, and returned five years later in a more reflective mood:

‘For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity’

He wrote of the poem’s composition: ‘No poem of mine was composed under circumstances more pleasant for me to remember than this. I began it upon leaving Tintern, after crossing the Wye, and concluded it just as I was entering Bristol in the evening, after a ramble of four or five days, with my Sister. Not a line of it was altered, and not any part of it written down till I reached Bristol.’

So where exactly is the poem set? Well, we have alighted on Symonds Yat, several miles upstream from Tintern, as it is the only place upstream of the abbey where all the features mentioned in the poem – cliffs, caves and cascades – can be experienced in one spot.

But does it really matter exactly where it was set on the river, it was probably a composition? What is more pertinent is that the structure of the poem exactly conforms to the view of the ‘picturesque’, as defined by the Rev Gilpin:

‘the most perfect river-views are composed of four grand parts: the area, which is the river itself; the two side-screens, which are the opposite banks, and lead the perspective; and the front-screen, which points out the winding of the river (‘O sylvan Wye! Those wanderer through tro’ the woods’, in Wordsworth’s poem) …they are varied by… the contrast of the screens…the ornaments of the Wye…. ground, wood, rocks, and buildings…and colour’.

Exactly the elements that are mentioned in the opening of ‘Tintern’.

And the idiolect of the poem is decidedly picturesque, including the ‘wildness’ of the truly sublime: these words all appear in the poem – lofty, dank, fire, fever, gleams, cataract, haunted, zeal, deep & gloomy and wild (three times).

Birth of tourism – the ‘properly Picturesque’ Wye tour

The lower Wye Valley is considered the birthplace of tourism in Britain, with its striking beauty, romantic ruins and viewing spots.

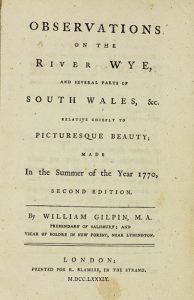

In 1782, the Reverend William Gilpin – who became known as ‘The High Priest of the Picturesque’- published ‘Observations on the River Wye’, the first illustrated tour guide to be published in Britain. Some of the most famous poets, writers and artists of the day made the pilgrimage to the great sights – among them Coleridge, Thackeray, Wordsworth and Turner. By 1800 a trip down the Wye was a must for people of taste and fashion who now had to holiday at home because of war in Europe, clutching a copy of Gilpin’s guidebook to help them find all the best views, and no doubt echoing the words of Gilpin’s when they got home: ‘If you have never navigated the Wye, you have seen nothing.’

In 1782, the Reverend William Gilpin – who became known as ‘The High Priest of the Picturesque’- published ‘Observations on the River Wye’, the first illustrated tour guide to be published in Britain. Some of the most famous poets, writers and artists of the day made the pilgrimage to the great sights – among them Coleridge, Thackeray, Wordsworth and Turner. By 1800 a trip down the Wye was a must for people of taste and fashion who now had to holiday at home because of war in Europe, clutching a copy of Gilpin’s guidebook to help them find all the best views, and no doubt echoing the words of Gilpin’s when they got home: ‘If you have never navigated the Wye, you have seen nothing.’

Gilpin’s ‘Observations on the River Wye’ contains an account of his passage south through Symonds Yat that matches all the main features of Wordsworth’s poem:

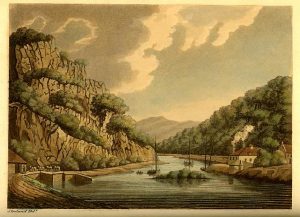

‘The river is wider, than usual, in this part; and takes a sweep round a towering promontory of rock; which forms the side-screen on the left; and is the grand feature of the view. It is not a broad, fractured face of rock; but rather a woody hill, from which large projections, in two or three places, burst out; rudely hung with twisting branches, and shaggy furniture; which, like mane round the lion’s head, give a more savage air to these wild exhibitions of nature. Near the top a pointed fragment of solitary rock (Long Stone), rising above the rest, has rather a fantastic appearance: but it is not without its effect in marking the scene.’

Although Wordsworth and Dorothy clearly made the tour on foot, most visitors set off by boat from Ross-on-Wye and sailed downriver to Chepstow over the course of two days. During the height of the Wye Tour’s popularity, there were up to ten ‘pleasure boats’ plying the route each day. This was the birth of ‘Picturesque tourism’ – travel that focused on an appreciation of scenery rather than just history or architecture.

These pleasure boats were equipped with cushioned seats and drawing tables, at which tourists would either read travel journals (usually Gilpin’s Observations…) or sit and rapidly sketch scenes that struck them as especially Picturesque. The boats also featured canopies to protect travellers from the sun, and crews to steer and row the boats downriver. The tourists left their boats below Coldwell Rocks and climbed up to the viewpoint at Yat Rock, before descending to rejoin their boats at New Weir. You can still get a boat tour here to this day, just not as romantic and glamorous!

THE WALK

‘Tintern’ is the perfect exposition of Wordsworth’s concept of a ‘spot in time’, from which the whole reflection and meaning of the poem springs. Below are the opening lines of the poem. Pretty excitingly, our walk locates all of them.

‘Five years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur. – Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves

‘Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit’s cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone…

… The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood

We set out from Symonds Yat Rock Car Park, take the chain ferry across from the Saracens Head pub (very kindly captained by the pub owner who charges us nothing) and then head south along the west bank, the river a soft inland murmur at this point on our left-hand side.

We set out from Symonds Yat Rock Car Park, take the chain ferry across from the Saracens Head pub (very kindly captained by the pub owner who charges us nothing) and then head south along the west bank, the river a soft inland murmur at this point on our left-hand side.

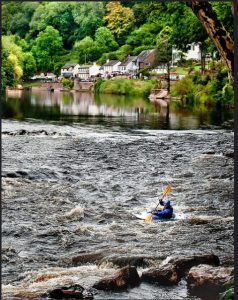

We pause by the rapids, level with the tiny island and look east, to behold these steep and lofty cliffs, with the Long Stone (‘the tall rock’) at the pinnacle.

We pause by the rapids, level with the tiny island and look east, to behold these steep and lofty cliffs, with the Long Stone (‘the tall rock’) at the pinnacle.

The West Bank: ‘on the banks of this delightful stream/We stood together’

We ‘repose Here’ by a clump of trees on the west bank – ‘under this dark sycamore’; and upstream, on the opposite bank, we see a cluster of buildings (Symonds Yat East) that seems to spring out of verdant nature, ‘plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts… these pastoral farms, Green to the very door.’

We ‘repose Here’ by a clump of trees on the west bank – ‘under this dark sycamore’; and upstream, on the opposite bank, we see a cluster of buildings (Symonds Yat East) that seems to spring out of verdant nature, ‘plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts… these pastoral farms, Green to the very door.’

Charcoal Burning & New Weir Forge: ‘the second grand scene on the Wye’

Charcoal Burning & New Weir Forge: ‘the second grand scene on the Wye’

On this steep wooded slope opposite, there used to be myriad charcoal burning sites and Wordsworth would have observed ‘wreaths of smoke/Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!’

Charcoal burning, in earth-covered mounds of ‘furnaces’ took place right across the hills. Oak coppices were set aside and were coppiced on a 14-year cycle.

‘many of the furnaces, on the banks of the river, consume charcoal, which is manufactured on the spot; and the smoke, issuing from the sides of the hills; and spreading its thin veil over part of them, beautifully breaks their lines, and unites them with the sky.’ Gilpin.

New Weir was notable for its ironworking, and the remains of New Weir Forge are still visible, first established in the 1570s (see the interpretation board here).

The Rapids

We drag ourselves up from our repose and walk on, with the sound of the rapids in our left ear, ‘The sounding cataract’, enjoyed today by enthusiastic young canoeists testing themselves.

We drag ourselves up from our repose and walk on, with the sound of the rapids in our left ear, ‘The sounding cataract’, enjoyed today by enthusiastic young canoeists testing themselves.

The rapids:

‘But what peculiarly marks this view, is a circumstance on the water. The whole river, at this place, makes a precipitate fall; of no great height indeed; but enough to merit the title of a cascade: tho to the eye above the stream, it is an object of no consequence. In all the scenes we had yet passed, the water moving with a slow, and solemn pace, the objects around kept time, as it were, with it; and every steep, and every rock, which hung over the river, was solemn, tranquil, and majestic. But here, the violence of the stream, and the roaring of the waters, impressed a new character on the scene: all was agitation, and uproar; and every steep, and every rock stared with wildness, and terror.’ Gilpin.

The cave

Soon after, on the steep slope opposite, close to the Solitary Rock, we spot a cave opening, ‘some Hermit’s cave, where by his fire/The Hermit sits alone.’ And other caves can be found at several points in the cliffs nearby, including

Soon after, on the steep slope opposite, close to the Solitary Rock, we spot a cave opening, ‘some Hermit’s cave, where by his fire/The Hermit sits alone.’ And other caves can be found at several points in the cliffs nearby, including  King Arthur’s Cave on the edge of Doward Hill.

King Arthur’s Cave on the edge of Doward Hill.

We head west to take a good look around the delightful Little Doward Iron Age Hill fort with its large open spaces full of wildflowers.

We head west to take a good look around the delightful Little Doward Iron Age Hill fort with its large open spaces full of wildflowers.

We cut down to the river and cross the bridge by the Biblins Adventure Centre and then head back along the disused railway line that hugs the east bank of the river. As we climb up towards Symonds Yat rock, we walk over two small flat areas with black soil underfoot; these are probably charcoal ‘hearths’ upon which charcoal was burned.

What better way to finish our walk than how Wordsworth finishes his poem:

…Nor wilt thou then forget,

That after many wanderings, many years

Of absence, these steep woods and lofty cliffs,

And this green pastoral landscape, were to me

More dear, both for themselves and for thy sake!

We are blessed with a spectacular view looking north of the bendy Wye north and east.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: Monmouth and Chepstow Museums to see sketches made on the Wye tour and Gilpin’s guide itself.

- Walk: The ‘Head for the Hillforts’ walk, download the pdf from https://www.wyevalleyaonb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Head-for-the-Hillforts-walk.pdf

- Download: a brilliant brochure on the Wye Valley Tour – https://www.wyevalleyaonb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Wye-Tour-Brochure.pdf

- Take: A boat tour with Kingfisher Cruises from Symonds Yat East

- Hire: A canoe and do it yourself; Guided Canoe Tours with Way2Go Adventures (www.way2goadventures.co.uk/trips-and-activities/canoeing-on-the-river-wye/) offer guided canoe trips down the Wye, including special Wye Tour excursions.

Leave a Reply