‘The idea of being authors was as natural to us as walking’ – Charlotte Brontë

‘I wish I were a girl again, half-savage and hardy, and free’ – Emily Brontë

‘The book becoming a map’ – Ted Hughes

KEY DATA

- Terrain: moorland. Only attempt this walk when conditions are reasonable.

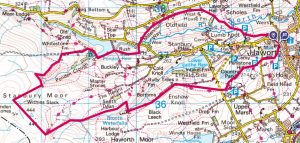

- Starting point: Haworth Tourist Office, BD22 8EF

- Distance: 14 km (8.8 miles)

- Walking time: 4 hrs 11 mins

- OS Map: OL 21. The map can also be found online at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10751101/Haworth-West-Yorkshire-Emily-Bronts-Wuthering-Heights

- Facilities: Pubs, shops, cafes

EMILY BRONTË (1818-1848)

The Brontë sisters lived most of their lives in Haworth, a small industrial town on the edge of the Yorkshire Moors. In 1847, their ‘literary mirabilis’, Charlotte published ‘Jane Eyre’, Anne published ‘Agnes Grey’ and Emily published ‘Wuthering Heights’; but within eight years all three had died, outlived by their father, who remained minister there for 41 years.

The Brontë sisters lived most of their lives in Haworth, a small industrial town on the edge of the Yorkshire Moors. In 1847, their ‘literary mirabilis’, Charlotte published ‘Jane Eyre’, Anne published ‘Agnes Grey’ and Emily published ‘Wuthering Heights’; but within eight years all three had died, outlived by their father, who remained minister there for 41 years.

Of all the Brontë novels, ‘Wuthering Heights’ most insistently features the landscape as both a setting and an influence on the characters’ behaviour. Even the name of the novel is a description of weather and landscape. Heathcliff is described through the elements of nature surrounding him. Misty and cold landscapes are used to highlight his unamiable nature and sullen mood. ‘My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary.’

Charlotte Brontë wrote about her sister: ‘Her native hills were far more to her than a spectacle; they were what she lived in, and by, as much as the wild birds, their tenants, or as the heather, their produce. Her descriptions, then, of natural scenery, are what they should be, and all they should be…Wuthering Heights was hewn in a wild workshop, with simple tools.’ She described her sister as ‘a nursling of the moors’.

The Brontës’ writings are imbued with the spirit of the moors around Haworth. ‘My sister Emily loved the moors,’ Charlotte wrote. ‘Flowers brighter than the rose bloomed in the blackest of the heath for her; out of a sullen hollow in a livid hillside her mind could make an Eden. She found in the bleak solitude many and dear delights; and not the least and best loved was – liberty.’

The landscape of Wuthering Heights is very different from the ‘carefully-fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers’ that Charlotte Brontë criticised Jane Austen’s fiction for depicting. Nature is often deeply inhospitable in the book, not easily subdued to human purpose, comfort or design. The landscape is thus never simply a setting or something to be contemplated in Brontë’s work, but an active and shaping presence in the lives of its characters.

So when thinking about ‘Wuthering Heights’, we should not see it simply as a novel that depicts or belongs to the moors. The final stanza of one of the Brontës’ most celebrated poems (we do not know if it was written by Emily or Charlotte) is concerned with both an essential human nature and an absolute freedom that goes beyond any particular place or time:

‘I’ll walk where my own nature would be leading:

It vexes me to choose another guide:

Where the gray flocks in ferny glens are feeding;

Where the wild wind blows on the mountain side.’

OUR WALK

Haworth Parish Church

Haworth Parish Church

We start at the parish church where the Brontës’ father was the vicar and survey the Brontë tomb, where all of the Brontë family, with the exception of Anne, are interred. The Brontë memorial chapel was added in 1963.

Brontë Parsonage Museum

Haworth Parsonage was the home of the Brontë family from 1820 to 1861 and the place where Charlotte, Emily and Anne wrote their novels. Now the Brontë Parsonage Museum, it houses the world’s largest collection of Brontë furniture, clothes and personal possessions.

Items on display include letters, notebooks and household artefacts. We peered at the ‘Little Books’ and were amazed to see how tiny the sisters’ handwriting was. We see the family dining room table where Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall were written and where the Brontë sisters shared their work with each other. A real writer’s table, complete with ink stains and candle burns.

Brontë Meadow

The Anne Stone lies in the top right-hand corner of Parson’s Field, a wildflower meadow behind the Brontë Parsonage Museum. It is carved with a poem by Scottish Makar, Jackie Kay.

It is one of a group of four stones placed in the landscape between the birthplace of the Brontë family in Thornton and the parsonage. There are three stones that celebrate the bicentenaries of the three sisters: Charlotte, Emily and Anne, and a fourth stone to mark the significance of the Brontës as a literary family. The Brontë Stones were erected in 2018. For another day, this makes a beautiful 9-mile route over the hills from Thornton to Haworth that takes in all four of the stones.

Brontë Waterfalls

Next, we head out onto the moors, or as Ted Hughes so brilliantly puts it in his poem Wuthering Heights, talking to his wife Sylvia Plath:

‘Then,

After the Rectory, after the chaise longue

Where Emily died, and the midget hand-made books,

The elvish lacework, the dwarfish fairy-work shoes,

It was the track from Stanbury. That climb

A mile beyond expectation, into

Emily’s private Eden…

It was all

Novel and exhilarating to you.

The book becoming a map. Wuthering Heights

Withering into perspective. We got there

And it was all gaze. The open moor’

We soon reach the Brontë waterfalls, a trickle in summer but quite a substantial flow in the winter.

‘We set off, not intending to go far; but though wild and cloudy it was fine in the morning; when we got about half-a-mile on the moors, Arthur suggested the idea of the waterfall; after the melted snow, he said it would be fine. I had often wished to see it in its winter power, so we walked on. It was fine indeed; a perfect torrent racing over the rocks, white and beautiful!’

A stone at the waterfalls is popularly called the Brontë chair, a chair-shaped rock in which the Brontës used to sit and tell stories.

Top Withens (Wuthering Heights)

Top Withens is generally accepted as the inspiration for the farmhouse of Wuthering Heights. Today it is a rubble of derelict buildings, but its remote setting and exposure to the elements remain unchanged. We can only imagine what it might have looked like. As Ted Hughes put it:

‘Was that crumble of wall

Remembering a try at a garden? Two trees

Planted, for a child to play under.’

‘Wuthering Heights is the name of Mr Heathcliff’s dwelling. `Wuthering’ being a significant provincial adjective, descriptive of the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather. Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there at all times, indeed; one may guess the power of the north wind blowing over the edge, by the excessive slant of a few stunted firs at the end of the house; and by a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun. happily, the architect had foresight to build it strong: the narrow windows are deeply set in the wall, and the corners defended with arge jutting stones.’

From here the route becomes a little less clear, but we basically aimed for the 444-metre trig point on Delf Hill above Ponden Kirk.

Ponden Kirk (Penistone Crag)

This large outcrop of gritstone was a favourite haunt of the Brontës. Emily named the rock Penistone Crag and she described the location as being the meeting place of Cathy and Heathcliff. At the base of the rock, there is a hole just large enough for an adult to climb through. Emily talks about this hole in the novel, calling it the ‘Fairy Cave’. Local legend relates that unattached people passing through the hole will marry within the year. Access to the ‘Fairy Cave’ is down a very steep embankment, only recommended if you are a very confident scrambler.

‘And what are those golden rocks like when you stand under them?’ she once asked. The abrupt descent of Penistone Crags particularly attracted her notice; especially when the setting sun shone on it and the topmost heights, and the whole extent of landscape besides lay in shadow. I explained that they were bare masses of stone, with hardly enough earth in their clefts to nourish a stunted tree. ‘And why are they bright so long after it is evening here?’ she pursued. ‘Because they are a great deal higher up than we are,’ replied I; ‘you could not climb them, they are too high and steep. In winter the frost is always there before it comes to us; and deep into summer I have found snow under that black hollow on the north-east side!’ (Wuthering Heights)

Ponden Hall (Thrushcross Grange)

We steadily descend Ponden Clough and reach Ponden Hall, the inspiration for Thrushcross Grange in Wuthering Heights. The date plaque above the main entrance identifies the rebuilt house as dating from 1801, the date that begins Wuthering Heights.

In 1824, during the great Crow Hill Bog Burst (a huge mudslide caused by a thunderstorm after days of rain), Anne, Emily and their brother Branwell were walking on the moor and took shelter at Ponden Hall. They subsequently became regular visitors, and often used the library, at that time considered one of the finest in West Yorkshire and boasting a Shakespeare first folio.

On the east gable end of the house, a tiny single-paned window is, according to local tradition, the window where Cathy’s ghost scratched furiously at the glass, trying to get in. ‘I muttered, knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching an arm out to seize the importunate branch; instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand!’

A challenging moorland trudge, the atmosphere and setting really captured for us the mood of Wuthering Heights, the use of landscape to express feelings both good and bad, like nature itself.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: The Brontë Parsonage Museum, bronte.org.uk

- Walk: the 14 km Brontë Stones walk, from Thornton to Haworth across the moor

- Walk: the 69 km Brontë Way

- Compare: the 1939 version of the film Wuthering Heights, starring Laurence Olivier & Merle Oberon, with the 1993 version, starring Ralph Fiennes & Juliette Binoche

- Listen To: The Emily Brontë Song Cycle

- Watch: ‘Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters’ (2016)

- Read: Peggy Hewitt, These Lonely Mountains

- Join an Expert Walking Tour: bronteadventures.co.uk/moors/haworth-walks

- Read: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes’s poems both titled ‘Wuthering Heights’

Leave a Reply