‘The Evergreen Valley’, ‘A city set in a garden’

‘The pines, the chines, steeply-rising cliffs, parks, gardens, heathlands, amusements, esplanades, sands, and sprawl add up to the strange unique character of Bournemouth. A fascinating, pine-scented phenomenon’. Thomas Hardy

‘The real Bournemouth is all pines and pines and pines and flowering shrubs, lawns, begonias, azaleas, bird-song, dance tunes, the plunge of the racket and creak of the basket chair.’ John Betjeman

The town’s motto is ‘Pulchritudo et Salubritas’: beauty and health.

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Pavements, beach and slopes

- Starting point: St Peter’s Churchyard, BH1 2EE

- Distance: 5 km (5.3 miles)

- Walking time: 2 hr 24 mins

- Map: The map can be found online at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10789972/Inspiring-Places-Bournemouth-Dorset

- Facilities: normal town facilities

BOURNEMOUTH

Bournemouth only came into existence in the 1810s, designed from its inception as a place to come and rest, recuperate and take the sea air. Its founder was Captain Lewis Tregonwell, who built a series of villas on his land to let out. The common belief that pine-scented air was good for lung conditions, and in particular tuberculosis, prompted Tregonwell to plant hundreds of Caledonian pine trees.

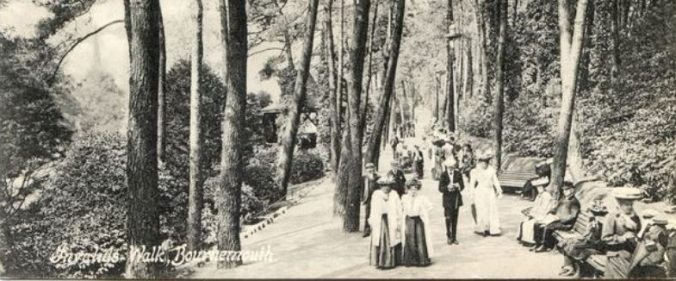

The town has been closely associated with its pines ever since;  its heraldic crest even has a pine tree atop it! A nineteenth-century History Of Hampshire says of Bournemouth ‘it is to the valuable medicinal properties of these trees, combined with the invigorating sea air, that the town owes its origin.’ Thomas Hardy referred to Bournemouth as ‘a fascinating, pine-scented phenomenon’. ‘The Pines Express’ ran daily from Manchester to Bournemouth in the first part of the twentieth century when tourists flocked to the resort by train.

its heraldic crest even has a pine tree atop it! A nineteenth-century History Of Hampshire says of Bournemouth ‘it is to the valuable medicinal properties of these trees, combined with the invigorating sea air, that the town owes its origin.’ Thomas Hardy referred to Bournemouth as ‘a fascinating, pine-scented phenomenon’. ‘The Pines Express’ ran daily from Manchester to Bournemouth in the first part of the twentieth century when tourists flocked to the resort by train.

Its credentials as a health resort were assured when it appeared in the 1841 book, ‘The Spas of England’, compiled by the much-respected physician Augustus Granville. With the arrival of the railway in 1885, it positively boomed, throwing up piers and promenades and miles of ornate brick offices and plump, stately homes, most of them with elaborate corner towers and other fancy embellishments.

By 1891, Thomas Hardy’s Sandbourne (Bournemouth) in ‘Tess of the d’Urbervilles’ was fully established:

‘This fashionable watering-place, with its eastern and its western stations, its piers, its groves of pines, its promenades, and its covered gardens, was, to Angel Clare, like a fairy place suddenly created by the stroke of a wand and allowed to get a little dusty.’’

By the midnight lamps he went up and down the winding way of this new world in an old one and could discern between the trees and against the stars the lofty roofs, chimneys, gazebos, and towers of the numerous fanciful residences of which the place was composed. It was a city of detached mansions; a Mediterranean lounging-place on the English Channel.’

‘The sea was near at hand, but not intrusive; it murmured, and he thought it was the pines; the pines murmured in precisely the same tones, and he thought they were the sea.’

Many writers have flocked to Bournemouth – and the one thing they seem to have in common is that they (or their family) went there to recuperate. Mary Shelley’s son bought her a place here in her old age, but she died before she could enjoy it, albeit she was buried in the town. Winston Churchill, who suffered from pneumonia from an early age, was a frequent visitor. Robert Louis Stevenson came to try and alleviate his tuberculosis, Henry James came to nurse his ailing sister who lived here, DH Lawrence, seriously ill with double pneumonia, spent some time here in 1912 to recuperate (‘The town is very pretty. When you look at it, it’s quite dark green with trees.’), JRR Tolkien spent much time here too because it was a good place for his wife’s convalescence.

Mary Shelley (1797-1851) and her family

Mary is world-renowned for writing the Gothic novel Frankenstein. She also edited and promoted the works of her husband, the Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Her mother was Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 –1797), an English writer and one of the founding feminist philosophers. She is best known for ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’ (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men but appear to be only because they lack education.

Her father, William Godwin (1756 – 1836) was also an independent thinker, being one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and anarchism. Godwin is most famous for two books that he published within the space of a year: ‘An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice’, an attack on political institutions, and ‘Things as They Are; or The Adventures of Caleb Williams’, an early mystery novel which attacks aristocratic privilege.

Perhaps not surprisingly their daughter was very independent-minded too. Her father described her at age 15 as ‘singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire of knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes almost invincible’. At the age of 17, she ran off with a married man, in the shape of Percy Shelley, who she fell in love with and saw as the embodiment of her parents’ liberal and reformist ideas. They married in 1816.

OUR WALK

St Peter’s Church, Bournemouth

So why, may you ask, is the whole of the Shelley clan buried in Bournemouth, when they never lived here? Well, the answer lies in the fact that the Shelleys’ son, Sir Percy Florence Shelley, had bought Boscombe Manor House, on the east side of Bournemouth, in 1849. He had originally intended it as a retirement home for his ailing mother, but she was too ill to move from London, where she died in 1851. Sir Percy and his wife, Jane, were seduced by the benign climate and wild beauty of the location and decided to move there themselves. There is a blue marque marking the house, which is now the Shelley Manor Medical Centre (Beechwood Avenue, BH5 1LX).

So why, may you ask, is the whole of the Shelley clan buried in Bournemouth, when they never lived here? Well, the answer lies in the fact that the Shelleys’ son, Sir Percy Florence Shelley, had bought Boscombe Manor House, on the east side of Bournemouth, in 1849. He had originally intended it as a retirement home for his ailing mother, but she was too ill to move from London, where she died in 1851. Sir Percy and his wife, Jane, were seduced by the benign climate and wild beauty of the location and decided to move there themselves. There is a blue marque marking the house, which is now the Shelley Manor Medical Centre (Beechwood Avenue, BH5 1LX).

Mary Shelley had asked to be buried with her mother and father; but Percy and Jane, judging the graveyard at St Pancras, where Mary’s parents were already buried, to be ‘dreadful’, chose to bury her instead at St Peter’s Church in Bournemouth, near their new home. And so it came to pass that all three were brought here, along with the heart of Percy Shelley, which had been taken from his body and preserved before his cremation in Italy. Sir Percy and Lady Jane were also later to be buried in the tomb. So, today we admire the large family tomb just adjacent to the church, which has become known as ‘The Tomb of Talents’.

Lewis Tregonwell, the founder of Bournemouth, is also buried here, and an inscription reads that he was ‘the first to bring (Bournemouth) into notice as a watering place by erecting a mansion for his own occupation having been his favourite retreat for many years before his death’.

Next, we head down to the shoreline and walk west along the undercliff to Alum Chine. In 1896 Capt. James Hartley, a former chairman of the Commissioners, said that an undercliff drive was ‘about all that was necessary to place Bournemouth in the very front rank of English health resorts, and enable us to compete with the attractions of the Riviera and other places abroad’, and by the turn of the century, it was there.

Alum Chine

The word ‘chine’ means a ‘deep, narrow ravine cut through soft rocks by a watercourse descending steeply to the sea’. There are half a dozen or so chines in Bournemouth, and they help give the place its distinctive character. They also tend to have a micro-climate that enables exotic plants to thrive in them.

The word ‘chine’ means a ‘deep, narrow ravine cut through soft rocks by a watercourse descending steeply to the sea’. There are half a dozen or so chines in Bournemouth, and they help give the place its distinctive character. They also tend to have a micro-climate that enables exotic plants to thrive in them.

As we walk up Alum Chine, we go under the suspension bridge, the site of which was the spot where the young Winston Churchill had climbed up onto the handrail and jumped for an overhanging pine branch in order to escape his (family) pursuers as part of a game. His younger brother Jack and a cousin watched in horror as the bough snapped. Churchill plunged 30 feet to the ground. For three days in 1892, the prolific author (43 book-length works in 72 volumes) and future Prime Minister lay in a coma followed by three months of bed rest to recover from a ruptured kidney and broken thigh.

The third bridge, a beam and post design, carries a plaque noting that Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) lived at Skerryvore overlooking this chine in the 1880s. He named his home at 61 Alum Chine Road after a famous lighthouse in Scotland built by his uncle. Although he was in poor health, suffering from tuberculosis (he had come to Bournemouth for the healthy sea air, and the pine trees reminded him of Scotland), he wrote much of his best work here, including ‘The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’. The house was destroyed in 1940,  but there is a memorial of a lighthouse to commemorate the spot near the foot of Robert Louis Stevenson Avenue.

but there is a memorial of a lighthouse to commemorate the spot near the foot of Robert Louis Stevenson Avenue.

Henry James (1843-1916) had travelled to Bournemouth to care for his sister, who had come to Bournemouth in the hopes of improving her health. One day James decided to walk up Alum Chine to visit Stevenson at his home. They immediately hit it off. After that evening, James came to Skerryvore nearly every night for dinner and literary discussions with Stevenson. A chair in the corner even became known as the ‘Henry James’ chair. James set one of his short stories, ‘The Middle Years’ (1893) in Bournemouth.

Branksome Chine

Gerard Durrell (1925-1995) and his family are most associated with Corfu, but nonetheless, he lived much of his life in Bournemouth. He spent his childhood at Berridge House, Spur Hill, Parkston, just west of where we turn down into Branksome Chine. This chine must have been his route to the beach…

JRR Tolkien (1892-1973) and his wife Edith, visited Bournemouth every summer for thirty years. For the first years, they frequented the Hotel Miramar (BH1 3AL), where there is a blue plaque. In the 1960s they bought a house (now demolished) in Lakeside Rd, Branksome Park, which had to be a bungalow, as Edith was virtually immobilised through ill health. It backed onto the pine-covered slope on our left as we head down.

John Betjeman must have wandered down this chine at some point too, for it features in one of his satirical poems, ‘The Town Clerk’s Views’ decrying the ‘modernization’ of the town:

‘Bournemouth is looking up. I’m glad to say

That modernistic there has come to stay.

I walk the asphalt paths of Branksome Chine

In resin scented air like strong Greek wine

And dream of cliffs of flats along those heights,

Floodlit at night with green electric lights.’

In truth, he rather liked the place: ‘The beauty of Bournemouth consists in three things, her layout, her larger villas and her churches. All are Victorian.’

In ‘Trains and Buttered Toast’, he talks about those pines: ‘The popularity of Bournemouth came with the popularity of pines and Scottish scenery. Two hundred years ago, Scotland and moors and heaths were considered rude and ugly. Then Sir Walter Scott started the craze for them; Landseer painted them later. Queen Victoria went to Balmoral. Prince Albert loved pine trees. Loyal Victorians, backed by literature and art as well as royalty, started to love them too. They saw in Bournemouth a place with all the romantic pine-clad, heath-covered verdure of Scotland but without so much of Scotland’s cold and rain. No wonder they filled it with houses. But they did it carefully.’

We walk back along the beach after a thoroughly engaging walk, our thoughts about Bournemouth utterly remodelled.

We walk back along the beach after a thoroughly engaging walk, our thoughts about Bournemouth utterly remodelled.

OTHER STUFF

- Check Out: Sunny Lawns (now The Durley Grange Hotel) in Durley Rd in Bournemouth. Radclyffe Hall, writer of the ground-breaking LGBT work ‘The Well of Loneliness’ (1928) was born here

- Read: ‘Notes from a Small Island’ (2015), by Bill Bryson, who spent two years working as a sub-editor for the Bournemouth Echo and wrote about his experiences here

- Visit During: The Arts by the Sea Festival, a mix of dance, film, theatre, literature, and music. https://artsbythesea.co.uk/

- Go To A Show: At the Shelley Theatre Trust. The ground floor bar is carved with quotes from Mary Shelley. http://www.shelleytheatre.co.uk/

Leave a Reply