‘Sweet city with her dreaming spires’

WALK DATA

- Distance: 5.4km (3.4 miles)

- Walk Time: 1hr 24 mins

- Start & finish: The Eagle & Child pub, 49 St Giles, OX1 3LU (the pub was purchased in Oct 2023 by The Ellison Institute of Technology, and they have promised to ‘refurbish and reopen the iconic venue’.)

- Map: Can also be found online at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10555486/Oxford-Literary-Rambles

- Facilities: All

OXFORD

Oxford has a higher number of literary associations per square foot count than any other spot in the UK and was the cradle of modern children’s literature.

More than 600 novels have been set here, ranging from romance to mystery, from the biographical to the fantastic, and the roll call of poets who started writing here would make a worthy Top 10 in anyone’s list of favourite poets.

So, what is it that makes Oxford such a literary hotbed? Well, the undergraduates, of course, but it’s also more than that – there is a special quality about the place that captures the creative mind.

Philip Pullman sums it up: ‘Oxford is a city that is steeped in storytelling. It’s a place where the past and the present jostle each other on the pavement and while of course that’s true of many cities in Britain, Oxford does seem to have a few extra dimensions in some strange way.’

The hyper-intelligent minds that come to Oxford have also often been at the vanguard of new writing movements – the lateral, sometimes off-the-wall thinking of the mathematician Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) that broke the mould of children’s literature, Tolkien’s vast knowledge of Old Norse sagas that informed a new genre of fantastical storytelling, Ronald Knox’s ‘10 Commandments of Detective Fiction’ based upon his scholarly need to codify and his religious convictions, the ‘cerebral fiction’ of Iris Murdoch, philosophy fellow at St Anne’s.

And, very conveniently, Oxford seems to offer a good location for almost every type of fiction: the ‘dreaming spires’ that provide a stylish backdrop to a Brideshead-style demi-monde; the narrow, medieval streets that lend themselves perfectly to mystery and intrigue; the numerous green spaces that offer up a dash of the pastoral idyll; the ‘everydayness’ of the covered market; the ‘otherness’ of the canal and the Jericho part of town; and finally the leafy suburbs of North Oxford, ideal for one of Barbara Pym’s rueful comedies of manners.

KEY LITERARY FIGURES

Lewis Carroll (1832–98)

- City bio: undergraduate in Maths at Christ Church, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher

- Work set in/influenced by city: Alice in Wonderland (1865), Through the Looking Glass (1871)

CS Lewis (1898–1963)

- City bio: His first civilian job after World War I was at the Oxford English Dictionary; Fellow and Tutor in English Literature at Magdalen College, where he served for 29 years.

- Work set in/influenced by city: The Chronicles of Narnia (1949–54)

JRR Tolkien (1897–1973)

- City bio: Fellow & Tutor of Merton College

- Work set in/influenced by city: Lord of the Rings (1955)

Philip Pullman (1946–)

- City bio: Undergraduate at Exeter College; then taught in the city

- Work set in/influenced by city: His Dark Materials, Lyra’s Oxford

Colin Dexter (1930–2017)

- City bio: Moved to Oxford in 1966 and lived there for the rest of his life.

- Works set in/influenced by the city: ‘Inspector Morse’ series. Colin Dexter calculated that by the time he ended his Inspector Morse series, he had killed off 81 Oxonians, including three heads of colleges.

Other:

- Matthew Arnold (1822–88): Oriel College, coined the description ‘sweet city with her dreaming spires’

- WH Auden (1907–73): Christ Church College, Oxford Professor of Poetry

- John Betjeman (1906–84): Dragon School, Magdalen College, ‘Summoned by Bells’

- Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–99): Balliol College, ‘Binsey Poplars’

- Dr Samuel Johnson (1709–84): Pembroke College

- Philip Larkin (1922–85): St John’s College

- Iris Murdoch (1919–99), a fellow of St Anne’s

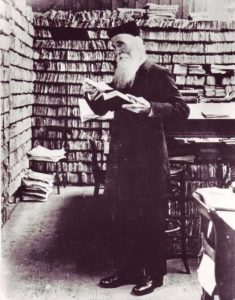

- James Murray (1837–1915): ‘Oxford English Dictionary’, 78 Banbury Rd

- John Ruskin (1819–1900): Christ Church

- Dorothy Sayers (1893–1957): ‘Gaudy Night’, Shrewsbury College (based on Somerville). Born at 1 Brewer Street (first house on left off St Aldate’s, blue plaque)

- Evelyn Waugh (1903–66): Hertford College

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900): Magdalen College

- …and many others.

THE WALK

- Make belief – the Inklings at The Child & Eagle

We start at a pub, The Eagle & Child, at the top of St Giles. A drink is not our recommended way to start a walk, so this initial stop is for research purposes only, rather than a stirrup cup. (Note; the pub is currently closed (last checked Oct 2023), there are plans for re-opening it but no firm dates. Check Google)

We start at a pub, The Eagle & Child, at the top of St Giles. A drink is not our recommended way to start a walk, so this initial stop is for research purposes only, rather than a stirrup cup. (Note; the pub is currently closed (last checked Oct 2023), there are plans for re-opening it but no firm dates. Check Google)

The pub was known affectionately as the ‘Bird and Baby’ by the two men who made it part of literary history: CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien. In the 1930s and 1940s, it was the favourite watering place of the ‘Inklings’, a group of writers, poets and religious thinkers who met regularly over a pint of beer to discuss literature and early drafts of their works, including ‘The Lord of the Rings’. For Tolkien, the sessions were ‘a feast of reason and a flow of soul’.

In the middle bar, we find the now framed (and famed) handwritten note to the landlord originally pinned up above the fireplace. Signed by members of the Inklings, it reads: ‘The undersigned, having just partaken of your ham, have drunk your health.’ As well as being erudite, they loved a good pint; our walk ends here too, so maybe that will be our opportunity.

We head south down St Giles, past – on our right – The Ashmolean, which houses a collection of Posie rings that inspired the One Ring in Tolkien’s ‘The Lord of the Rings’. Then, past St Mary Magdalen’s Church, where two men fell from its high tower in the Inspector Morse series ‘Servants of All The Dead’.

- Books, books, books

The glory of Broad Street opens up on our left, and the biggest vehicular risk becomes bicycles, scores and scores of them, many propped up one against another on college walls with signs forlornly forbidding it, and others being propelled by students at speed but not often specific direction along the highway, sometimes whilst also on the phone or shouting out to a friend in the street.

Oxford is (unsurprisingly) a very bookish place, and now we are sauntering towards the most bookish quarter of them all. For this is Blackwell’s territory, first the Art and Poster Shop on the right (you can’t miss it, there’s an Anthony Gormley ‘man’ atop the roof), then Blackwell’s Music Shop, and finally the main shop on the left at No. 51. Its Norrington Room has earned a place in the Guinness Book of Records as the largest single room selling books, with three miles of shelving in total. Of course, you might get stuck here buying books you can’t afford, much as John Betjeman did in his day:

‘I wandered into Blackwell’s, where my bill

Was so enormous that it wasn’t paid

Till ten years later, from the small estate

My father left…’

(‘Summoned by Bells’, the ‘Opening World’)

Opposite, we walk past Wren’s Sheldonian Theatre (1669), at which most of our motley crew of literary figures matriculated but somewhat fewer graduated; and thence to the  Bodleian Library, which has more than 13 million printed items, putting Blackwell’s 250,000 or so titles somewhat in the shade.

Bodleian Library, which has more than 13 million printed items, putting Blackwell’s 250,000 or so titles somewhat in the shade.

We look up at the gargoyles just before we enter the Schools’ Quadrangle and are surprised to see not just the typical grotesque carved human or animal faces, but also the depiction of several children’s novels. We spot Tweedledum and Tweedledee, Aslan, The Green Man, Three Men in a Boat and more. These were the fruits of a school design competition, unveiled by Philip Pullman. It is a place he is very familiar with in his novels, featuring prominently in ‘His Dark Materials’ and ‘La Belle Sauvage’ (‘Bodley’s Library’).

The Duke Humfrey’s Reading Room is filled with rare books, including manuscripts of the gospels of the Bible from the 3rd century, a Shakespeare First Folio and a copy of the Gutenberg Bible. Tolkien would have been very familiar with the 14th-century ‘Red Book of Hergest’, which is now housed here. He later created his own fictional Red Book of Westmarch, as written by Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, telling the story of The Lord of the Rings. Several of Tolkien’s manuscripts are now in the library.

As well as Tolkien, many other writers including Oscar Wilde and CS Lewis studied here. A more recent writer Julie Kavanagh wrote about how the place inspired her: ‘The point, though, was never the degree (which I haven’t collected), it was English literature and Oxford itself. Oxford is still the love of my life, and I work whenever I can in the Bod, sitting where I always sat: U44 in the Upper Reading Room with its view of the Radcliffe Camera and the fins of All Souls. It’s where I’m writing this last sentence now.’

Behind the reading room is the Chancellor’s Court, in which Oscar Wilde went on trial for debt and Shelley for promoting atheism.

The Radcliffe Camera (aka the ‘Rad Cam’) has long been the symbol of Oxford and has been featured many times in books and on the screen, including in several episodes of Inspector Morse. Tolkien remarked that the building resembled Sauron’s temple to Morgoth in ‘Lord of the Rings’. Dorothy Sayers’ 1936 mystery novel Gaudy Night is set here, and one of the most important concluding conversations between Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane takes place on the balustraded circular rooftop, a perfect setting for a murder mystery.

The Radcliffe Camera (aka the ‘Rad Cam’) has long been the symbol of Oxford and has been featured many times in books and on the screen, including in several episodes of Inspector Morse. Tolkien remarked that the building resembled Sauron’s temple to Morgoth in ‘Lord of the Rings’. Dorothy Sayers’ 1936 mystery novel Gaudy Night is set here, and one of the most important concluding conversations between Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane takes place on the balustraded circular rooftop, a perfect setting for a murder mystery.

Oxford has a medieval street structure at its core, and Brazenose Lane, which we pass on our right, is the last street remaining to have a single drainage channel or ‘kennel’ running along its middle. Today it has great charm and quaintness, but in the nineteenth century it was described as ‘always dismal and dreary in the daytime and barely lighted by two or three lamps at night’.

John Ruskin famously described the university as the ‘Temple of Apollo but felt very differently about Brazenose Lane: ‘In the centre of that temple, at the very foot of the dome of the Radclyffe, between two principal colleges, the lane by which I walked from my own college half an hour ago to this place – Brasen-nose Lane – is left in a state as loathsome as a back alley in the East end of London.’ It’s a tough life being an aesthete.

And it’s probably for that very reason – a ‘normal’ street amongst the ‘gilded spires’ – that it is a favourite haunt for crime fiction writers, most notably Inspector Morse. The series ‘Whom The Gods Would Destroy’ used this location extensively.

We explore down the much more ethereal St Mary’s Passage, following the route CS Lewis would have taken myriad times on his way to preaching at St Mary’s Church at the bottom. We pass a solitary gas lantern in front of us, then on the right, there is a door with two engraved fauns and a maned, lion-like face carved into the centre of it. We have stumbled on a little corner of Narnia right in the heart of Oxford, the gas lantern showing us the way, and the representations on the door of Mr Tumnus and Aslan welcoming us.

We explore down the much more ethereal St Mary’s Passage, following the route CS Lewis would have taken myriad times on his way to preaching at St Mary’s Church at the bottom. We pass a solitary gas lantern in front of us, then on the right, there is a door with two engraved fauns and a maned, lion-like face carved into the centre of it. We have stumbled on a little corner of Narnia right in the heart of Oxford, the gas lantern showing us the way, and the representations on the door of Mr Tumnus and Aslan welcoming us.

We come out of the wardrobe again onto the High Street, but the sense of marvel doesn’t stop, with the glorious view eastwards and the elegant twist of the street. Wordsworth, a Cambridge man, may well have been at this very point when he wrote this sonnet in 1820:

‘I slight my own beloved Cam, to range

Where silver Isis leads my stripling feet;

Pace the long avenue, or glide adown

The stream-like windings of that glorious street.’

- Poets striking poses

Passing University College on the other side of the street, we can just make out a portico behind the wall where the Shelley Memorial is to be found, a sculpture depicting the dead poet washed up on the shore at Viareggio in Italy after his drowning at the age of 29. Shelley matriculated in 1810, but his undergraduate career lasted fewer than two terms: in March 1811 he and a friend were expelled from University College following the publication of their pamphlet ‘The Necessity of Atheism’. Shortly afterwards Shelley wrote to his father, ‘I hope it will alleviate your sorrow to know that for myself I am perfectly indifferent to the late tyrannical proceedings at Oxford.’ Thus putting paid to the notion that we all used to be much more respectful to our parents.

Passing University College on the other side of the street, we can just make out a portico behind the wall where the Shelley Memorial is to be found, a sculpture depicting the dead poet washed up on the shore at Viareggio in Italy after his drowning at the age of 29. Shelley matriculated in 1810, but his undergraduate career lasted fewer than two terms: in March 1811 he and a friend were expelled from University College following the publication of their pamphlet ‘The Necessity of Atheism’. Shortly afterwards Shelley wrote to his father, ‘I hope it will alleviate your sorrow to know that for myself I am perfectly indifferent to the late tyrannical proceedings at Oxford.’ Thus putting paid to the notion that we all used to be much more respectful to our parents.

Another poet who liked to do things his own way was John Betjeman, an undergraduate at Magdalen in the 1920s. He usually wore outrageous clothes – lavender trousers with an orange shirt – spent too much money dining out, making illicit trips to London by train, feeding the deer in Magdalen on sugar lumps soaked in port, and too much time cultivating the image of himself as a perfect aesthete.

He fell foul of CS Lewis, his English tutor, turning up late to a tutorial and wearing, to Lewis’ disgust, ‘eccentric bedroom slippers’. His verse autobiography ‘Summoned by Bells’ describes these early years:

‘My walls were painted Bursar’s apple-green;

My wide-sashed windows looked across the grass

To tower and hall and lines of pinnacles.

The wind among the elms, the echoing stairs,

The quarters, chimed across the quiet quad

From Magdalen tower and neighbouring turret-clocks…’

He arrived at university with a teddy bear, which gave his contemporary Evelyn Waugh the idea for Aloysius, Sebastian’s teddy in ‘Brideshead Revisited’. He acted, wrote poetry and architectural notes for student publications, and became editor of the student magazine ‘Cherwell’. And he neglected his studies, so that in the end, like Shelley, he left Oxford without a degree.

However, not all poets struck a pose and did poorly academically. The studiously ‘normal’ brigade of poets was led by TS Eliot, who disliked Oxford and much preferred London, writing ‘Oxford is very pretty, but I don’t like to be dead.’ Despite escaping Merton and leaving Oxford life, Eliot was happy enough to receive an honorary doctorate, and the TS Eliot Theatre can be found in Rose Lane Gardens, where there is a bust of him by Jacob Epstein. There is also a notable collection of Eliot’s first editions and ephemera in the library.

Philip Larkin was another poet who didn’t take to the Oxford ways. His novel ‘Jill’ (1942) is about a socially inept northern boy who struggles to fit in at the university. His ‘Poem about Oxford’ reflects Larkin’s mixed feelings of irritation and fascination regarding the place where he was a student at St John’s College. He reminisces about ‘a full notecase/Dull Bodley, draught beer and dark blue’. And when, later in life, a friend suggested he be nominated as the Oxford Professor of Poetry, Larkin confessed to revulsion for ‘a lot of sherry-drill with important people’, and that a literary party was his idea of ‘hell on earth’. Oxford just wasn’t his sort of place; seaports were more his thing, the very opposite in tone and spirit (see our chapters on Hull and Belfast).

There are two parts of Magdalen we are particularly keen to see, the Deer Park and Addison’s Walk. CS Lewis writes about the deer park: ‘My big sitting room looks north and from it I can see nothing, not even a gable or a spire, to remind me that I am in town. I look down on a stretch of ground which passes into a grove of immemorial forest trees, at present coloured autumn red. Over it stray deer.’ No doubt he would have been dismayed if he had discovered that his indolent student Betjeman had been feeding them alcohol-imbued sugar lumps.

Addison’s Walk, a charming, secluded path running alongside the Cherwell, was also inspirational to CS Lewis and his writing friends: ‘Hugo Dyson stayed the night with me in College… Tolkien came too, and did not leave till 3 in the morning… We began in Addison’s Walk just after dinner on metaphor and myth – interrupted by a rush of wind which came so suddenly on the still warm evening and sent so many leaves pattering down that we thought it was raining…’

Outside the gates between the Deer Park and a bridge leading to Addison’s Walk, there is a plaque with a CS Lewis poem inscribed on it, ‘What the Bird Said Early in the Year’; it was placed here in 1998, marking the centenary of Lewis’s birth.

‘I heard in Addison’s Walk a bird sing clear:

This year the summer will come true. This year. This year.

Winds will not strip the blossom from the apple trees

This year nor want of rain destroy the peas.

This year time’s nature will no more defeat you.

Nor all the promised moments in their passing cheat you.

This time they will not lead you round and back

To Autumn, one year older, by the well worn track.

This year, this year, as all these flowers foretell,

We shall escape the circle and undo the spell.

Often deceived, yet open once again your heart,

Quick, quick, quick, quick! – the gates are drawn apart.’

Caught up in this sense of timelessness and Oxford-ness, we cross the road from Magdalen and enter the ancient and delightful Botanic Garden.

- Inspired by Nature

Lewis Carroll was a frequent visitor to The Botanic Garden, and it was a source of inspiration for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The Garden’s water lily house can be seen in the background of Tenniel’s illustration of ‘The Queen’s Croquet-Ground’.

Tolkien often spent his time in the garden reposing under his favourite tree, a European Black Pine. This enormous Austrian pine was much like the Ents in ‘The Lord of the Rings’, the walking, talking tree-people of Middle-Earth. The last known photograph of him, taken in 1973, is of him standing alongside this tree as if it is his great friend. Sadly, it was blown down in 2014, and the only evidence we could find of it was some repaired damage to the eighteenth-century wall onto which it had fallen.

We sit on a bench towards the back of the garden, which oddly for such a well-kept garden has some graffiti inscribed upon it: ‘L loves W’. With a jolt, we realise that this is the very bench where, in Philip Pullman’s trilogy ‘His Dark Materials’, Lyra and Will promise to sit here for an hour at noon on Midsummer’s Day every year, so that they may feel each other’s presence next to one another in their own worlds. We don’t quite stay for an hour, but we find it hard to drag ourselves away from this natural paradise.

We sit on a bench towards the back of the garden, which oddly for such a well-kept garden has some graffiti inscribed upon it: ‘L loves W’. With a jolt, we realise that this is the very bench where, in Philip Pullman’s trilogy ‘His Dark Materials’, Lyra and Will promise to sit here for an hour at noon on Midsummer’s Day every year, so that they may feel each other’s presence next to one another in their own worlds. We don’t quite stay for an hour, but we find it hard to drag ourselves away from this natural paradise.

‘Nature is so near’ in Oxford, as WH Auden observed, almost wherever you are in the centre; and nowhere does it feel more immediate than here, a place of beauty and tranquillity, of inspiration and reflection.

- Dreaming Spires

As we stroll down Rose Lane, so one of Oxford’s most quintessential views opens up in front of us, Christ Church and the meadows, the epitome of ‘the dreaming spires’.

As we stroll down Rose Lane, so one of Oxford’s most quintessential views opens up in front of us, Christ Church and the meadows, the epitome of ‘the dreaming spires’.

‘Sebastian lived at Christ Church, high in Meadow Buildings.’ That’s the building on our right, a splendid Victorian Gothic edifice, and we can imagine Sebastian propped up on the windowsill, with his Betjeman-inspired teddy bear Aloysius, looking down and waving us up. ‘He was alone when I came, peeling a plover’s egg taken from the large nest of moss in the centre of the table.’

Or is it Harold Acton, poet and aesthete, that we hear? His rooms, also in the Meadow Building, were painted in lemon yellow, and he used to stand on his balcony and read his poems through a megaphone to people passing by.

We are walking through this magical space on a sunny day, redolent of these lines from ‘Brideshead Revisited’: ‘Her autumnal mists, her grey springtime, and the rare glory of her summer days – such as that day – when the chestnut was in flower and the bells rang out high and clear over her gables and cupolas, exhaled the soft airs of centuries of youth.’

As we reach St Aldate’s, we look across at the Alice Shop at No. 83, where Alice Liddell, the daughter of the Dean of Christ Church and the inspiration for Alice in Wonderland, used to buy her barley sugar sweets. Tenniel’s two illustrations of the shop in the original publications had all details reversed because, of course, it was in the looking glass.

We can imagine Lewis Carroll popping in here with the three Liddell sisters before their famous boat trip from Salter’s Boatyard at Folly Bridge (the boatyard is still there at the bottom of St Aldate’s) up the Isis to Godstow. It was on this outing in July 1862 that Carroll began threading the story of a bored girl named Alice looking for adventure. The girls loved it and they begged him to write ‘Alice’s Adventures’. The poem that prefaces the book refers to that day:

‘

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence

Our wanderings to guide.’

In Christ Church’s Great Hall there is a portrait of the young Lewis Carroll, and one of the stained-glass windows depicts scenes from the book. Guarding the fire, the hall also has brass firedogs that have long necks in the way Alice was portrayed when she grew in size in the Pool of Tears.

Lewis Carroll lived in rooms in the main (Tom) Quad’s northwest corner from 1862 until his death: first in a ground-floor suite, where he wrote ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’, then in an upper suite looking over St Aldate’s, which we pass under as we head up the street.

WH Auden kept coming back to Oxford. He started out as an undergraduate at Christ Church in the late 1920s, with rooms in the north‐west comer of Peckwater Quad, on the third floor, looking onto Blue Boar Street, where he would hold court with the small group of acolytes who began to assemble around him, reading aloud his own poems and those of other poets whose work impressed him. This is one of the poems he would have read out:

‘Nature is so near: the rooks in the college garden

Like agile babies still speak the language of feeling;

By the tower the river still runs to the sea and will run,

And the stones in that tower are utterly

Satisfied still with their weight.’

(‘Oxford’)

The tower he refers to is most likely the Tom Tower, which we have just walked under, and the river of course the Thames at the bottom of the meadows.

In 1956, Auden became Oxford University’s Professor of Poetry, running on the manifesto ‘a poet will talk nonsense, but it will probably be interesting nonsense.’ During his few weeks each year in Oxford, he would sit in his slippers in the Cadena Café (in Cornmarket, now demolished), granting audiences to aspirant poets, a scene that reminded one observer of ‘a huge, craggy-faced Socrates among the tidy women shoppers’.

The great poet returned to the college in his final years and lived in the Brewhouse, situated in the garden of the Canon’s Residence at the southwest corner of Tom Quad, by the cobbled walk to the meadow. There is a small black triangle, bearing a dedication to him, in Christ Church Cathedral.

- Whodunnits?

Next, we head up Blue Boar Street and arrive at a favourite Oxford pub, The Bear Inn. The snug oak-panelled two-roomed interior is home to a remarkable collection of nearly 5,000 snippets of gentlemen’s neckties, started in the 1950s when customers exchanged the end of their tie for a pint (or two) of beer. They mostly indicate membership of clubs, regiments, and schools – the Royal Gloucester Hussars, the Imperial Yeomanry, the Punjab Frontier Force, Lloyds of London Croquet Club etc.

Next, we head up Blue Boar Street and arrive at a favourite Oxford pub, The Bear Inn. The snug oak-panelled two-roomed interior is home to a remarkable collection of nearly 5,000 snippets of gentlemen’s neckties, started in the 1950s when customers exchanged the end of their tie for a pint (or two) of beer. They mostly indicate membership of clubs, regiments, and schools – the Royal Gloucester Hussars, the Imperial Yeomanry, the Punjab Frontier Force, Lloyds of London Croquet Club etc.

In Colin Dexter’s novel, ‘Death is Now My Neighbour’, Inspector Morse enters the pub armed with a photograph of a man wearing a maroon tie with a narrow white strip, hoping to learn which school or club the man had once attended. It was a long shot: ‘A bit like a farmer looking for a lost contact lens in a ploughed field,’ he confessed to the landlord. But then his eyes widened with expectation only to be disappointed in an instant when Sonya came up with the answer: ‘Yo’’ll find one just like that in the tie rack at Marks & Spencer.’

Oxford has been a mecca for crime fiction since The Golden Age of Detective Fiction, the 1920s and 1930s era of classic murder mystery novels of similar patterns and styles. The rules of the game were codified in 1929 by Ronald Knox, a fellow of Trinity College. His ‘10 Commandments of Detective Fiction’ included:

- Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

- No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

- The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

To see the rest of the rules, look at https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/tips-masters/ronald-knox-10-commandments-of-detective-fiction

Like most rule-setters, he was never the best at actually playing the game and his crime novels are largely forgotten. He is perhaps best remembered today for the biography that Evelyn Waugh, a friend, wrote about him.

We head up Albert Street into the Covered Market, opened in 1777 in response to a general wish to clear ‘untidy, messy and unsavoury stalls’ from the main streets. It’s a refreshing dose of normality after all the ‘dreaming spires’, the sort of market I have come across in many a provincial Midlands town, full of shops and cafés and people pushing past each other, lingering at windows, sampling cheese, choosing cuts of meat and chatting.

In Joanna Trollope’s ‘The Men and the Girls’ it serves as the location for an attempted reconciliation between Kate, who has just left her long-term partner, and her angry teenage daughter Joss:

‘She had said she would meet Joss by the hot little shop that baked huge American cookies on the spot, which you could carry away, warm and scented in an excitingly unEnglish kind of paper bag. Joss was late. Kate put her hands in her trouser pockets and leaned against a blind wall of the cookie shop, and watched the people throng past, the local people buying cabbages and pounds of sausages, and the tourists, drifting in the mildly, aimlessly inquisitive way peculiar to all tourists.’

This was Ben’s Cookies, near the entrance we come in, and it is still possible to carry a freshly baked cookie away in a paper bag.

The Covered Market also features in Philip Larkin’s novel ‘Jill’, which centres on John Kemp, an undergraduate whose ordinary Northern upbringing and social inexperience set him apart from his fellow undergraduates. John visits the covered market and finds it a site of comfort, where he knows how to ‘choose lettuces with sound fresh hearts, and radishes that were not fibrous’. The Covered Market is also a favourite haunt for heroine Lyra and her friends in Pullman’s Northern Lights.

We head out the northern end of the market, track west along Market Street, then cross Cornmarket up Frewin Court to enter the main entrance of the Oxford Union, impressed by the terracotta lettering above the door.

The Oxford Union Library is a thing of Pre-Raphaelite splendour. Its dramatic murals were created by a group of budding pre-Raphaelites at the end of the 1850s before they were famous, done for love and soda water. This group included Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. The murals depict stories from the fifteenth century ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’, a text many English undergraduates will recall with a mixture of fondness and ennui.

- A sense of ‘otherness’ – The Canal and Jericho

Next, we track east, dropping down onto the Oxford Canal on Bridge Street. Today it provides a tranquil walking route and a lifestyle choice for canal boat dwellers, but in its heyday delivering coal and supplies it would have been a grubby and unwelcoming spot.

We cross over Mount Place footbridge, the way Lyra would have come back from Port Meadow, the site of the Horse Fair where the disappearance of a young boy ‘from a gyptian family she knew’ helps to trigger her adventures. Much of Lyra’s Oxford is set here in Jericho, a now-fashionable area between the canal and the Woodstock Road that is home to ‘little brick terraced houses in the narrow lanes’, many painted in an appealing palette of pastel colours. How different it is from what Pullman called the ‘Oxford beauty – grand and stony and masculine’.

Just on the right along Canal Street is Combe Road, named after a famous Oxford University Press printer. We glimpse the row of houses where murders were committed in Colin Dexter’s ‘The Dead of Jericho’. The line between fact and fiction seems to have been blurred for many. Some years later Dexter spoke to an estate agent who was trying to sell a property in Combe Road. She was having difficulties selling it because of rumours that the quiet little road had seen both a murder and a suicide – rumours entirely based on the fictional Inspector Morse story.

The series also features the exterior of the Bookbinders Arms on our left, named after the bookbinders who made their way here each evening after work at the printworks nearby.

Turning right into Cardigan Street, we spot the old Castlemill Boatyard at the end, now re-named Jericho Wharf in the modern parlance, (long) awaiting hopefully sensitive re-development – planning approval was finally granted in Feb 2023, including a new working boatyard. Philip Pullman was at the forefront of a campaign to retain a boat-repair facility here. The life and bustle that had been here provided the seeds of his description of the canal basin as ‘crowded with narrow boats and butty boats, with traders and travellers, and the wharves along the waterfront in Jericho were bright with gleaming harness and loud with the clop of hooves and the clamour of bargaining’. Regular visitors were ‘gyptian families, who lived in canalboats, came and went with the spring and autumn fairs, and were always good for a fight.’ The gyptians were outsiders, and Jericho was very much their natural habitat.

Alongside Jericho Wharf is the splendid St Barnabas Church, designed in an Italianate style by Sir Arthur Blomfield and opened in 1869. It features in Thomas Hardy’s novel ‘Jude the Obscure’ as St Silas’s Church. As a young man, Hardy had worked for Blomfield in London, and his reference in the novel to ‘the church of ceremonies’ reflects St Barnabas’ importance within the Oxford Movement, which attempted to encourage the Church of England to adopt more of the rituals of the Catholic faith. Jude is another classic ‘outsider’, a working-class hero coming to grief because of failing to gain admittance to a college in forbidding ‘Christminster’. The church is also mentioned in ‘Brideshead Revisited’, and in a poem by John Betjeman, both Waugh and Betjeman being taken by Anglo-Catholicism.

Alongside Jericho Wharf is the splendid St Barnabas Church, designed in an Italianate style by Sir Arthur Blomfield and opened in 1869. It features in Thomas Hardy’s novel ‘Jude the Obscure’ as St Silas’s Church. As a young man, Hardy had worked for Blomfield in London, and his reference in the novel to ‘the church of ceremonies’ reflects St Barnabas’ importance within the Oxford Movement, which attempted to encourage the Church of England to adopt more of the rituals of the Catholic faith. Jude is another classic ‘outsider’, a working-class hero coming to grief because of failing to gain admittance to a college in forbidding ‘Christminster’. The church is also mentioned in ‘Brideshead Revisited’, and in a poem by John Betjeman, both Waugh and Betjeman being taken by Anglo-Catholicism.

Now we head back along Cardigan Street and Jericho Street to Walton Street, where we pass the Jericho Tavern on our left. In the seventeenth century, travellers arriving in Oxford from the north after the city gates were shut could take refuge here. This inn was the origin of the area’s name, the idea of being ‘just without’ the city’s walls. In recent years it has been a refuge for start-up musical acts, spawning the careers of no less than Supergrass and Radiohead, who played their first-ever gig here in 1986.

- The meaning of words

Our final highlight is the Oxford University Press (‘Fell Press’ in Lyra’s Oxford), or OUP, originally based at Clarendon House next to the Sheldonian and re-located here in 1830. The Press’s most famous publication is of course the ‘Oxford English Dictionary’ (OED), first published in 1929 and now only available online.

James Murray started work on it in the 1870s, with the wildly optimistic goal of completing it in ten years. He got to work in a corrugated iron outbuilding called the ‘Scriptorium’ at his home at 78 Banbury Road, which was lined with wooden planks, bookshelves, and more than a thousand pigeonholes for the quotation slips. Anything addressed to ‘Mr Murray, Oxford’ would always find its way to him, and such was the volume of post sent by Murray and his team that the Post Office erected a special post box outside Murray’s house (still there). But by the time he died in 1915, he had completed less than half of it, having defined words starting with A–D, H–K, O–P, and T.

James Murray started work on it in the 1870s, with the wildly optimistic goal of completing it in ten years. He got to work in a corrugated iron outbuilding called the ‘Scriptorium’ at his home at 78 Banbury Road, which was lined with wooden planks, bookshelves, and more than a thousand pigeonholes for the quotation slips. Anything addressed to ‘Mr Murray, Oxford’ would always find its way to him, and such was the volume of post sent by Murray and his team that the Post Office erected a special post box outside Murray’s house (still there). But by the time he died in 1915, he had completed less than half of it, having defined words starting with A–D, H–K, O–P, and T.

Up until this time, Dr Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) had been the most highly regarded of its genre. He had been an undergraduate at Pembroke College. James Murray adopted many of Johnson’s explanations without change, acknowledging that ‘when his definitions are correct, and his arrangement judicious, it seems to be expedient to follow him.’ In the end, the OED reproduced around 1,700 of Johnson’s definitions, marking them simply ‘J’. Being a Scotsman though, Murray unsurprisingly didn’t adopt Johnson’s definition of oats: ‘a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people’.

Between 1919 and 1920, Tolkien was employed by the OED, researching etymologies in the ‘Waggle’ to ‘Warlock’ range; later he parodied the principal editors as ‘The Four Wise Clerks of Oxenford’ in the story Farmer Giles of Ham. And Julian Barnes worked here as a lexicographer for three years, after graduating from Magdalen in 1968.

Perhaps less well-known is that the Press was commissioned by Lewis Carroll to print the first edition of ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’. Although he had paid for 2,000 copies to be produced, the run was stopped after just 50, when Tenniel complained about the quality of the illustrations. You can judge for yourselves: there is a copy in the press’s museum.

A short walk back from here to The Eagle & Child, a walk that Charles Williams, a notable editor at the OUP and a regular member of The Inklings, would have made most Tuesdays for a pint and a chat. As we turn right onto the Woodstock Road, we have visions of Iris Murdoch peddling a creaky old bicycle down the road, which was how her husband-to-be John Bayley first saw her and fell in love with her. As she famously said:

‘The bicycle is the most civilized conveyance known to man. Other forms of transport grow daily more nightmarish. Only the bicycle remains pure in heart.’

Here we are, back at the start, or in TS Eliot’s more elegant phrasing: ‘In my beginning is my end.’

OTHER STUFF

Pit Stops with literary connections:

- The Eagle & Child, 49 St Giles, OX1 3LU (see text)

- The Bear, 6 Alfred Street, OX1 4EH (see text)

- Café Loco, 85-87 St Aldate’s, OX1 1RA. Mad Hatter-themed café

- Morse Bar at the Randolph Hotel, Beaumont Street, OX1 2LN. Inspector Morse’s favourite watering hole

- Turf Tavern, 4-5 Bath Place, OX1 3SU. In Evelyn Waugh’s ‘Brideshead Revisited’ Charles says, ‘The Turf in Hell Passage knew us well.’ Thomas Hardy ate here, and it was also a regular haunt of Ernest Hemingway and Colin Dexter. My English teacher Philip Balkwill brought us here for a pint after watching a Shakespeare play at one of the colleges.

- Eastgate Hotel, 73 High Street, OX1 4BE. Since Tolkien was a Fellow of Merton College and Lewis of Magdalen College, the Eastgate was a convenient and regular meeting place.

Top 5 Bookshops:

- Blackstone’s, 48–51 Broad Street, OX1 3BQ (see text)

- Oxford University Press Bookshop, 116–117 High Street, OX1 4BZ.

- Arcadia Bookshop, 4 St Michael’s Street, Oxford OX1 2DU. Quirky second-hand collection

- Oxfam Bookshop, 56 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3LU. The very first Oxfam bookshop to open back in 1987.

- Last Bookshop, 25 Walton Street, OX1 2HQ. Great value, also has a small café.

Libraries:

- The Bodleian and Radcliffe Camera (see text)

- Merton College Library, which opened in the fourteenth century, is the oldest academic library in the world to be still in continual use. Mentioned by the enigmatic Jay Gatsby in Fitzgerald’s ‘The Great Gatsby’, who claimed he was an ‘Oxford Man’.

- The Old Library, Oxford Union (1850s), a triumph of Pre-Raphaelite design (see text)

Oxford Poetry Library, a pedal-powered mobile poetry library that aims to be a free and open resource of poetry for readers of all backgrounds, tastes, and ages. Find times and locations at: https://oxfordpoetrylibrary.com/hours-and-locations/

Oxford Poetry Library, a pedal-powered mobile poetry library that aims to be a free and open resource of poetry for readers of all backgrounds, tastes, and ages. Find times and locations at: https://oxfordpoetrylibrary.com/hours-and-locations/

Literary Activities:

- Literary Festival: www.oxfordliteraryfestival.org – March/April

- Poetry Tour: The Oxford Playhouse runs a poetry tour of Oxford in the summer

- Alice’s Day – July 7th each year, celebrating all things related to Alice

- Literary Guided walks: www.oxfordwalkingtours.com, Philip Pullman’s Oxford Official Tour; Inspector Morse and Lewis 2-hour walking tour of Oxford

- Visit: Oxford University Press Museum, open from 10 am–4 pm Monday–Friday

- Take a boat trip: Salter’s Yard offers an Alice in Wonderland cruise that visits several places where Dodgson rowed with the Liddell children.

- Download: The Oxford Poetry Library Poetry Pin which allows you to discover poetry by walking with your device in a localised zone. Each pin on the map represents a poem. To read, just walk over to a pin.

Leave a Reply