‘Why go to Saint-Juliot? What’s Juliot to me?

I was but made fancy

By some necromancy

That much of my life claims the spot as its key.’‘A Dream or No’ (1912-1913)

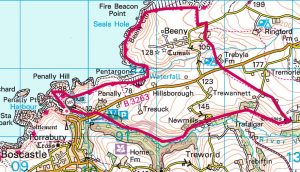

KEY DATA

Terrain: Steep undulations in places, firm going

Starting point: Boscastle Harbour, PL35 0HD

Distance: 8.8 kms (6.1 miles)

Time: 3 hrs 10 mins

OS Map: OS Explorer 111. This route can be found online at: https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/7699426/Boscastle-Cornwall-Thomas-Hardy

Facilities: Youth Hostel, pubs, shops, toilets in Boscastle

THOMAS HARDY (1840-1928)

Thomas Hardy was a young architect working to restore the church of St Juliot when he met Emma Gifford here in the spring of 1870. Emma was living in the rectory with her sister, the rector’s wife.

Other visits followed, and Hardy and Emma fell in love. Beeny Cliff, the Valency Valley and the surrounding area became the backdrop to their courtship. Thomas Hardy’s third novel, ‘A Pair of Blue Eyes’ (1873) is set in St Juliot and Emma was the model for the heroine of the book.

Sadly, their marriage turned sour; but when Emma died in 1912, Hardy, consumed with remorse, returned to St Juliot and wrote the Love Poems (1912-13) in her memory; they are amongst the greatest love poems of the twentieth century.

‘I found her out there

On a slope few see,

That falls westwardly

To the salt-edged air,

Where the ocean breaks

On the purple strand,

And the hurricane shakes

The solid land.’‘I Found Her Out There’ (1912-1913)

For Thomas Hardy, the landscape was intrinsic to creating mood and meaning. The nurturing of nature in ‘The Woodlanders’ when Giles Winterborne is planting saplings, the natural and mystical powers of Egdon Heath in ‘The Return of the Native’, or the dramatic intensity of Stonehenge in ‘Jude the Obscure’… Hardy’s characters seem to be formed by their landscape.

THE WALK

We set out from the Youth Hostel in Boscastle early in the morning, retiring to bed the night before excruciatingly early as all dutiful hostelers must.

The harbour is a natural inlet protected by two stone harbour walls, built in the sixteenth century by Sir Richard Grenville, and the only significant harbour for twenty miles or so along the coast. When Hardy first visited in 1870, Boscastle was a busy, bustling place. It was a commercial port and all heavy goods had to be carried by sea. More than a dozen ketches and schooners traded regularly from here. Many vessels brought supplies in from South Wales and Bristol, but even cargoes of timber direct from Canada came in here. It only began to decline when the railway arrived in North Cornwall in 1893, and today we see just a handful of small fishing and leisure boats.

It was at exactly this spot we are standing at on the quay that Stephen Smith disembarked in ‘A Pair of Blue Eyes’ to pursue his love for Elfride having made some money in India.  ‘And thus, waiting for night’s nearer approach, he watched the placid scene, over which the pale luminosity of the west cast a sorrowful monochrome, that became slowly embrowned by the dusk. A star appeared and another, and another. They sparkled amid the yards and rigging of the two coal rigs lying alongside, as if they had been tiny lamps suspended in the ropes. The masts rocked sleepily to the infinitesimal flux of the tide, which chucked and gurgled with idle regularity in nooks and holes of the harbour walls.’

‘And thus, waiting for night’s nearer approach, he watched the placid scene, over which the pale luminosity of the west cast a sorrowful monochrome, that became slowly embrowned by the dusk. A star appeared and another, and another. They sparkled amid the yards and rigging of the two coal rigs lying alongside, as if they had been tiny lamps suspended in the ropes. The masts rocked sleepily to the infinitesimal flux of the tide, which chucked and gurgled with idle regularity in nooks and holes of the harbour walls.’

We clamber up along the South West Coast Path to Penally Point, under which there is a blowhole that thumps and snorts about an hour on either side of low tide, blowing a horizontal waterspout halfway across the harbour entrance.

The wind is blowing hard as we reach the point. Although only September, we can start to understand Emma’s words about the landscape: ‘no summer visitors can have a true idea of its power to awaken heart and soul’. The expanse of the sky is huge, the shrieking of the gannets and seagulls proving a dramatic cacophony around us as we head up and down each ridge and gully along the coast.

There’s a natural viewpoint for the Pentargon Falls with a marker just before we cross a stone stile and head up the fields towards a farm. We admire the entire waterfall as it spills over a sheer 100-foot drop. ‘The small stream here found its death. Running over the precipice it was dispersed in spray before it was halfway down, and falling like rain on projecting edges, made minute grassy meadows of them.’

The Pentargon waterfalls are the point that Elfride repairs to in ‘A Pair of Blue Eyes’ with a telescope to search for the arrival of the steamboat on which Steven is returning:

The Pentargon waterfalls are the point that Elfride repairs to in ‘A Pair of Blue Eyes’ with a telescope to search for the arrival of the steamboat on which Steven is returning:

‘Having ascended and passed over a hill behind the house, Elfride came to a small stream. She used it as a guide to the coast. It was smaller than that in her own valley, and flowed altogether at a higher level. Bushes lined the slopes of its shallow trough; but at the bottom, where the water ran, was a soft green carpet, in a strip two or three yards wide. In winter, the water flowed over the grass; in summer, as now, it trickled along a channel in its midst.’

The spot looks exactly the same today. It was also here that her second suitor Mr Knight loses his footing and has to be saved by Elfride. And from this event was first coined the phrase ‘cliff-hanger’ to describe a suspense novel. So there you go.

Beeny Cliff

Emma Hardy wrote of this spot: ‘Scarcely any author and his wife could have had a much more romantic meeting. A beautiful sea-coast, and the wild Atlantic ocean rolling in, with its magnificent waves and spray, its white gulls and black choughs and grey puffins, its cliffs and rocks and gorgeous sun settings.’ Hardy wrote: ‘March 10 (1870) Went with ELG (Emma Lavinia Gifford) to Beeny Cliff. She on horseback … On the cliff … the run down to the edge.’ Emma remembers ‘scampering up and down the hills on my beloved mare, wanting no protection, the rain going down my back. … The villagers stopped to gaze when I rushed down the hills … for no one dared except myself to ride in such wild fearless fashion.’

‘Beeny Cliff’ (1912-13) describes this scene most wonderfully:

‘O the opal and the sapphire of that wandering western sea,

And the woman riding high above with bright hair flapping free –

The woman whom I loved so, and who loyally loved me.The pale mews plained below us, and the waves seemed far away

In a nether sky, engrossed in saying their ceaseless babbling say,

As we laughed light-heartedly aloft on that clear-sunned March day.A little cloud then cloaked us, and there flew an irised rain,

And the Atlantic dyed its levels with a dull misfeatured stain,

And then the sun burst out again, and purples prinked the main.– Still in all its chasmal beauty bulks old Beeny to the sky,

And shall she and I not go there once again now March is nigh,

And the sweet things said in that March say anew there by and by?What if still in chasmal beauty looms that wild weird western shore,

The woman now is – elsewhere – whom the ambling pony bore,

And nor knows nor cares for Beeny and will laugh there nevermore.’

We are left breathless by the poignancy of the moment, reciting this poem on the clifftop looking out from the ‘wild weird western shore’. We eventually come down from our ‘high’ and start to head south over the hills towards St Juliot, stopping for a snack behind the shelter of a hawthorn hedge. Momentarily, as the wind picks up, the last lines of Hardy ‘s ‘The Voice’ (1912-13) come vividly to mind:

‘The wind oozing thin through the thorn from norward

And the woman calling.’

Finally, I get it, why the wind is coming from the north, it’s an onshore breeze.

St Juliot’s parish is entirely rural and the only settlements are the tiny hamlets of Beeny and Tresparrett. Emma moved to St Juliot Rectory in 1868 to join her sister Helen, wife of the Reverend Caddell Holder. Before we reach the church, we pass this rectory on our right, where Hardy met Emma.

It is a very attractive house, with a steeply pitched slate roof with double gable ends to front and rear, overhanging eaves and ornate-shaped and pierced barge boards. It had only been built just over 20 years prior to Hardy’s first visit, so no doubt he would have cast his architect’s eye over it, it is very much in the style of the late 1840s.

Today the rectory is a thriving B&B and, judging by the Trip Advisor comments you will receive a very warm welcome. Better still, if you are a Hardy-phile, you get the choice of Emma’s Room, The Rector’s Room or Mr Hardy’s Room to stay in. The garden is delightfully laid out and is occasionally open to the public in the early summer in aid of charity. There is a long herbaceous border that leads to Hardy’s Seat, a place as peaceful today as when Thomas and Emma sat there all those years ago, looking out over the Valency Valley.

One of my favourite poems is set here. Just walk through the verandah down the steps (very) early one spring morning and experience the mood of ‘At the Word Farewell’ (1912-13):

‘She looked like a bird from a cloud

On the clammy lawn,

Moving alone, bare-browed

In the dim of dawn.

The candles alight in the room

For my parting meal

Made all things withoutdoors loom

Strange, ghostly, unreal.’

And soon we arrive at St Juliot Church, dedicated to St Julitta’s, set in an isolated location above the valley. In the 1860s it was in very poor condition and in urgent need of restoration. An aspiring young architect by the name of Thomas Hardy was given the job.

And soon we arrive at St Juliot Church, dedicated to St Julitta’s, set in an isolated location above the valley. In the 1860s it was in very poor condition and in urgent need of restoration. An aspiring young architect by the name of Thomas Hardy was given the job.

Hardy visited St Juliot in 1870 and stayed at the Old Rectory while surveying the church. Hardy’s plans are still on display in the church. The main alterations he made were the restoration of the tower and the re-arranging of the aisles. When he returned in Spring 1913 after Emma’s death, he installed the memorial tablet to Emma on the north wall of the church, crafted by a Boscastle stonemason.

The Hardy Society gave the church a beautifully engraved window to mark the Millennium (2000). The window was designed by Simon Whistler and depicts three of Hardy’s poems, ‘When I set out for Lyonesse’, ‘Under the Waterfall’ and ‘Beeny Cliff’.

As we head out the south side of the churchyard, we pass a striking medieval wheel-headed cross. In addition to serving the function of reinforcing the Christian faith amongst those who passed, the crosses were also waymarkers, in this case pointing the way to Boscastle, where we are headed.

Valency Valley

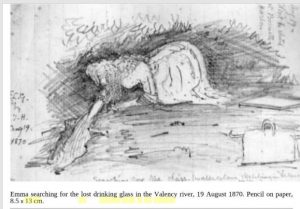

In her memoir, Some Recollections, Emma Hardy writes, ‘often we walked down the beautiful Valency Valley to Boscastle Harbour where we had to jump over stones and climb over a low wall by rough steps, to come out on great wide spaces suddenly, with a sparkling little brook into which we once lost a tiny picnic tumbler.’ We are taking this very route now.

Thomas Hardy’s poem ‘Under the Waterfall’ (1912-13) tells the story of losing this drinking glass:

‘For, down that pass,

My love and I

Walked under a sky

Of blue with a leaf-wove awning of green,

In the burn of August, to paint the scene,

And we placed our basket of fruit and wine

By the runlet’s rim, where we sat to dine;

And when we had drunk from the glass together,

Arched by the oak-copse from the weather,

I held the vessel to rinse in the fall,

Where it slipped, and sank, and was past recall,

Though we stooped and plumbed the little abyss

With long bared arms. There the glass still is.’

Hardy described the spot earlier in the poem as in ‘the purl of a little valley fall, about three spans wide and two spans tall, over a table of solid rock.’

As we descend, we keep raising our hands and stretching out our thumbs and little fingers to measure for three-span widths, and finally, we think we have it – is this the very spot?! A fall with roughly the right proportions and a slab of rock beneath. Naturally, we stop to have our picnic here, and we are tempted to stick our hands in the rapid flow to see if the glass might still be there…

The stop gives us time to pause and reflect on the perfectness of the natural world around us – a lively river, ancient oak trees, verdant pasture and abundant wildlife, especially butterflies.

Our walk concludes as we come back into Boscastle Harbour.

OTHER STUFF

Stay: in the Old Rectory, St Juliot www.stjuliot.com

Read: ‘Some Recollections, Emma Hardy’, first published in 1961

Leave a Reply