‘The great inviolate place had an ancient permanence which the sea cannot claim’

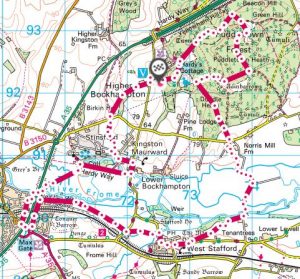

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Undulating, potentially wet and muddy

- Starting point: Thorncombe Wood car park, Higher Bockhampton, DT2 8QJ

- Distance: 15.4 km (9. 6 miles)

- Walking time: 4 hrs 20 mins

- OS Map: OS Explorer OL15. The map can be found online at: https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/9601721/Bockhampton-The-Frome-Valley-Dorset-Thomas-Hardy

- Facilities: Café and toilets at Kingston Maurward College

THOMAS HARDY (1840-1928)

The novels and poems of Thomas Hardy are more dominated by a sense of place than those of any other English writer. ‘I am convinced,’ he once wrote, ‘that it is better for a writer to know a little bit of the world remarkably well than to know a great part of the world remarkably little.’

The novels and poems of Thomas Hardy are more dominated by a sense of place than those of any other English writer. ‘I am convinced,’ he once wrote, ‘that it is better for a writer to know a little bit of the world remarkably well than to know a great part of the world remarkably little.’

The little bit of the world that Hardy knew remarkably well was the part of England in which he was born and where he lived most of his life: Dorset and the surrounding counties, or Wessex as he coined it. And within that, the ‘colossal and mysterious’ Egdon Heath is perhaps the most significant, a symbolic means of evaluating the various characters and of assessing their tendencies towards self-destruction or survival.

Hardy was brought up on the edge of two very different geographic features. In front of his childhood home, the land slopes away to rich water meadows, taking us into the Valley of the Great Dairies (The Frome Valley) and ‘Tess of the d’Urbervilles’ country. Behind, the gorse and heather of the heath reaches almost to the back door of his parents’ cottage, and this is ‘Return of the Native’ country. And when he was a bit older, he walked each day to school in Dorchester (a 5-mile round trip), ‘Mayor of Casterbridge’ country.

His grandmother used to take him for walks onto Egdon Heath when he was a little boy, telling him stories of bygone days and ways, which fascinated him throughout his life. Naturally, he became a very keen walker and he walked long distances throughout his life, crisscrossing the very same paths we take on our walk today. He puts it simply in the poem ‘Paying Calls’:

‘I went by footpath and by stile

Beyond where bustle ends,

Strayed here a mile and there a mile

And called upon some friends.’

The friend we go in search of today is, of course, Thomas Hardy and his many vivid characters.

Wessex was to Hardy what the Lake District was to Wordsworth. He spent much of his life here, first as a child and young man and then as an established literary figure at Max Gate (echoes of the contrast between Dove Cottage and Rydale Mount).

The walk

We start our walk at Thorncombe Wood, an ancient woodland made up of different species, which is little changed since Hardy’s day. In the opening of ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’ he tells us that:

‘To dwellers in a wood almost every species of tree has its voice as well as its feature. At the passing of the breeze the fir-trees sob and moan no less distinctly than they rock; the holly whistles as it battles with itself; the ash hisses amid its quiverings; the beech rustles while its flat boughs rise and fall. And winter, which modifies the note of such trees as shed their leaves, does not destroy its individuality.’

We soon reach Hardy’s Cottage, a quaint thatched building where Thomas Hardy was born, built in 1800 by his great‐grandfather, a builder and stonemason as was his grandfather and father. He grew up here and it became the heart of his writing landscape. He wrote short stories, poetry and novels including ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’ and ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’ here.

We soon reach Hardy’s Cottage, a quaint thatched building where Thomas Hardy was born, built in 1800 by his great‐grandfather, a builder and stonemason as was his grandfather and father. He grew up here and it became the heart of his writing landscape. He wrote short stories, poetry and novels including ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’ and ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’ here.

He describes it in ‘Domicilium’, written when he was 16:

‘Our house stood quite alone, and those tall firs

And beeches were not planted. Snakes and efts

Swarmed in the summer days, and nightly bats

Would fly about our bedrooms. Heathcroppers

Lived on the hills, and were our only friends;

So wild it was when we first settled here.’

It is well worth looking inside, and for us at least it is the little details that really bring the place to life. One of the windows into the garden was originally the entrance door, which Hardy describes in the poem ‘The Self‐Unseeing’:

‘Here is the ancient floor,

Footworn and hollowed and thin,

Here was the former door

Where the dead feet walked in.’

Leaving the cottage, we head east, passing several swallet holes, deep craters in the ground formed when water dissolves the surface rock. Hardy was fascinated by these as a child, and had lain in one, buried among the ferns ‘reflecting on his experiences of the world so far as he had got’.

He also of course put them to good use in his novels, using a swallet hole as a stage on which to set the burgeoning love affair of Troy and Bathsheba in ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’:

‘The pit was a saucer-shaped concave, naturally formed, with a diameter of about thirty feet, and shallow enough to allow the sunshine to reach their heads. Standing in the centre, the sky overhead was met by a circular horizon of fern.’

Mistover Knap is a bit further along this path, where Beacon Hill is marked on the map today. Hardy describes Mistover Knap as a small hamlet consisting of two cottages and ‘the only remaining house – that of Captain Vye and Eustacia, which stood quite away from the small cottages, and was the loneliest of lonely houses on these thinly populated slopes’.

We swing back down to the old Roman Road, now a permissive footpath. Hardy walked on it from a very early age:

‘The Roman Road runs straight and bare

As the pale parting-line in hair

Across the heath….But no tall brass-helmed legionnaire

Haunts it for me. Uprises there

A mother’s form upon my ken,

Guiding my infant steps, as when

We walked that ancient thoroughfare,

The Roman Road.’

It is along this very stretch of Roman Road, bisecting Egdon Heath, that Diggory Venn is travelling at the start of ‘The Return of the Native’ and, ‘though the gloom had increased sufficiently to confuse the minor features of the heath, the white surface of the road remained almost as clear as ever’.

The opening of ‘The Return of the Native’ is an elegy to Egdon Heath:

‘It was a spot which returned upon the memory of those who loved it with an aspect of peculiar and kindly congruity. Smiling champaigns of flowers and fruit hardly do this, for they are permanently harmonious only with an existence of better reputation as to its issues than the present. Twilight combined with the scenery of Egdon Heath to evolve a thing majestic without severity, impressive without showiness, emphatic in its admonitions, grand in its simplicity.’

To our left now we see the Rainbarrows, three Neolithic barrows. It is exactly at this spot that Diggory Venn stopped to rest his tired ponies.

‘The scene before the reddleman’s eyes was a gradual series of ascents from the level of the road backward into the heart of the heath. It embraced hillocks, pits, ridges, acclivities, one behind the other, till all was finished by a high hill cutting against the still light sky. The traveller’s eye hovered about these things for a time, and finally settled upon one noteworthy object up there. It was a barrow. This bossy projection of earth above its natural level occupied the loftiest ground of the loneliest height the heath contained.’

Then he spies a lone silhouette (Eustacia Vye) on the summit of the barrow, disturbed by the furze cutters climbing up with their loads to light a huge fire on the summit

‘The loads were all laid together, and a pyramid of furze thirty feet in circumference now occupied the crown of the tumulus’. And as the bonfire gets going, Hardy describes it: ‘It seemed as if the bonfire-makers were standing in some radiant upper story of the world, detached from and independent of the dark stretches below. The heath down there was now a vast abyss, and no longer a continuation of what they stood on; for their eyes, adapted to the blaze, could see nothing of the deeps beyond its influence.’

We head up to the spot where the fire must have been. Suddenly we are transposed to ‘Tess of the d’Urbervilles’ country and the view that Tess first has of the fertile valley below:

‘…she found herself on a summit commanding the long sought for vale, the valley of the Great Dairies, the valley in which milk and butter grew to rankness … the verdant plain so well watered by the river Var or Froom.’

As we come down to the Dorchester to Tincleton road, we see the site of the Quiet Woman Inn which is now Duck Dairy House. It was featured in ‘The Return of the Native’, Damon Wildeve being its landlord. It long ago ceased to be a pub, which is probably just as well because the pub sign, a decapitated woman carrying her own head, would surely put off today’s drinkers.

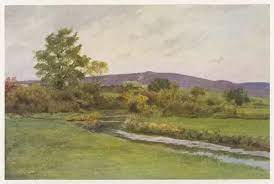

The Valley of the Great Dairies

We are now in the heart of the Frome Valley, the ‘Valley of the Great Dairies’ symbol of fecundity for Thomas Hardy:

‘Amid the oozing fatness and warm ferments of the Froom Vale, at a season when the rush of juices could almost be heard below the hiss of fertilization, it was impossible that the most fanciful love should not grow passionate. The ready bosoms existing there were impregnated by their surroundings.’

It is of course in this valley that Angel Clare first courted Tess, and these are halcyon days for them:

‘…they roved along the meads by creeping paths which followed the brinks of trickling tributary brooks, hopping across by little wooden bridges to the other side, and back again. They were never out of the sound of some purling weir, whose buzz accompanied their own murmuring, while the beams of the sun, almost as horizontal as the mead itself, formed a pollen of radiance over the landscape.’

We find ourselves making almost exactly the same journey across the meadows and, as we cross the main river, we are reminded of that most famous scene of all as Angel helps the parlour maids one by one across the flooded brook:

‘When the girls reached the most depressed spot they found that the result of the rain had been to flood the lane over-shoe to a distance of some fifty yards…

The girl’s (Tess’s) cheeks burned to the breeze, and she could not look into his eyes for her emotion. It reminded Angel that he was somewhat unfairly taking advantage of an accidental position; and he went no further with it. No definite words of love had crossed their lips as yet, and suspension at this point was desirable now. However, he walked slowly, to make the remainder of the distance as long as possible; but at last they came to the bend, and the rest of their progress was in full view of the other three. The dry land was reached, and he set her down.’

Likewise, we make it to the other side, and to our left, we see Lower Lewell Farm, thought to be Talbothays, where Tess worked so happily and started her life again: ‘She appeared to feel that she really had laid a new foundation for her future’.

Next, we walk upstream to West Stafford, passing over a piece of land called Talbothays to this day, which Hardy’s father had owned. In the 1890s Thomas Hardy built Talbothays Lodge on it, for his brother and two sisters. His sister Mary died there, an event reflected in ‘Logs on the Hearth’ and ‘In the Garden’. The house stands today very much as it would have done then, as does the sundial mentioned in the second poem, inscribed with the initials of the three siblings.

The church of St Andrew in West Stafford was the setting for Tess and Angel Clare’s marriage, and ‘the three bells of Talbothays parish Church were rung for her wedding’.

Stafford House, which we now see in front of us, is the setting of the short story ‘The Waiting Supper’. The waterfall above which Nicholas Long used to wade during his arduous commutings, and where Bellston was drowned, can still be seen.

But we take the footpath on the left just before the big house and continue heading upstream alongside the river. We think it worth passing some rather unsightly sewage works, to cross the rail line (which used to take Talbothay’s milk up to London, the ‘fitful white streak of steam’) and head up the hill to Max Gate.

Hardy designed and lived in Max Gate from 1885 until his death in 1928. It was there that he wrote ‘Tess of the d’Urbervilles’, ‘Jude the Obscure’ and ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’, as well as much of his poetry. It is at the geographic epicentre of his writing universe. It was almost inevitable that he should have fallen for the plot of land given its position, although the house itself feels rather austere. It certainly worked for him as a place to write, and one of my favourite poems set here is ‘An August Midnight’:

‘A shaded lamp and a waving blind,

And the beat of a clock from a distant floor:

On this scene enter – winged, horned, and spined –

A longlegs, a moth, and a dumbledore;

While ‘mid my page there idly stands

A sleepy fly, that rubs its hands…

Thus meet we five, in this still place,

At this point of time, at this point in space.

– My guests besmear my new-penned line,

Or bang at the lamp and fall supine.

“God’s humblest, they!” I muse. Yet why?

They know Earth-secrets that know not I.’

Max Gate became a magnet to the great and famous from the worlds of literature, art, music, politics and academia. Hardy’s guests included Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, W.B. Yeats and Henry Newbolt, Mrs Patrick Campbell, A.E. Housman, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Gustav Holst, Sir James Barrie, Siegfried Sassoon, T.E. Lawrence, Robert Graves, Edmund Blunden, Marie Stopes, Ramsey Macdonald, The Prince of Wales and many others. Amidst much serious conversation, we imagine TE Lawrence doing a wheelie on the driveway.

Max Gate became a magnet to the great and famous from the worlds of literature, art, music, politics and academia. Hardy’s guests included Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, W.B. Yeats and Henry Newbolt, Mrs Patrick Campbell, A.E. Housman, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Gustav Holst, Sir James Barrie, Siegfried Sassoon, T.E. Lawrence, Robert Graves, Edmund Blunden, Marie Stopes, Ramsey Macdonald, The Prince of Wales and many others. Amidst much serious conversation, we imagine TE Lawrence doing a wheelie on the driveway.

The final stage of our walk follows the route Hardy took most Sunday afternoons to see his parents at Higher Bockhampton and, after they died, to visit their graves in Stinsford churchyard. In the ‘Dead Quire’ this is the route he would have followed home:

‘(crossing) the leaze

From Moaning Hill towards the mead –

The Mead of Memories.’

Moaning Hill is the field above the church, named after the sound of the wind in the trees there.

St Michael’s in Stinsford was Thomas Hardy’s parish church, which he came to regard as a hallowed spot, where the life of his family and the community played out. His father and grandfather came here every Sunday to worship. They also played violin and cello in the church band. Its choristers and congregation were immortalised in ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’. It is also where his mother and father first met, as described in the poem ‘A Church Romance (Mellstock: circa 1835)’:

‘She turned in the high pew, until her sight

Swept the west gallery, and caught its row

Of music-men with viol, book, and bow

Against the sinking sad tower-window light.

She turned again; and in her pride’s despite

One strenuous viol’s inspirer seemed to throw

A message from his string to her below,

Which said: “I claim thee as my own forthright!’

We see the graves of Hardy’s parents, his sister Mary and his first wife Emma, which he used to visit regularly, and his own grave where his heart is buried (the rest of his remains being in Westminster Abbey).

We cut back along the ‘embowered path beside the Froom’ and into Bockhampton. Opposite the old Post Office stands the School, which opened in 1848; Hardy was the first pupil to enter the new school building, arriving on the day of opening, and awaiting tremulously and alone, as recalled in ‘He Revisits His First School’:

‘I should not have shown in the flesh,

I ought to have gone as a ghost;

It was awkward, unseemly almost,

Standing solidly there as when fresh,

Pink, tiny, crisp-curled,

My pinions yet furled

From the winds of the world.’

The way back to Hardy’s Cottage from here is the route Hardy must have taken many, many times.

OTHER STUFF

Visit: Hardy’s Cottage (NT), see www.nationaltrust.org.uk/hardys-cottage for details

Visit: Max Gate (NT), see www.nationaltrust.org.uk/max-gate for details

Visit: Hardy’s study at the Dorset County Museum in Dorchester, see https://dorsetcountymuseum.org/ for details

Visit: William Barnes’ grave at Winterborne Came (DT2 8NT), marked by a tall Celtic cross. William Barnes was a rural poet who wrote in the Dorset dialect. He was a good friend of Thomas Hardy, who often walked across from Max Gate to visit him.

Read: TE Lawrence and the Max Gate Circle (1995), by Ronald Knight

Read: D. H. Lawrence’s Study of Thomas Hardy (1936)

Visit: Maiden Castle (English Heritage, DT2 9PP), two miles SW of Dorchester, which Hardy described as ‘being like the green-clothes skeleton of a gigantic antediluvian creature.’ It is where Henchard, with his telescope trained on the Weymouth road, watched Farfrae’s meetings with Elizabeth-Jane in ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’.

Leave a Reply