‘All voices should be read as the river’s mutterings’

The Inspiration for this walk: ‘Dart’

We have holidayed in Salcombe in South Devon pretty much every year for the last twenty. And bit by bit, as the boys have got older and stronger (and before I get older and weaker), we have walked further and further afield; once all the way to Plymouth (hugely lengthened by all the estuaries) and once up the Dart Estuary from Dartmouth to Totnes.

We became so enamoured by the Dart that we were determined to discover its source this year, way up on Dartmoor. And whilst researching its exact location, I came across this gem of a book, Alice Oswald’s ‘Dart’, which takes us down the river in a far more visceral way than any tourist fodder possibly could.

ALICE OSWALD (1966-)

Alice Oswald is a nature poet who has been described as writing in a style ‘between Hughesian deep myth and Larkinesque social realism’. She is more a ‘pastoral realist’ than a ‘pastoral idealist’, perhaps because of her own experiences as a gardener (John Clare was also a gardener for part of his life). She is a widely acclaimed poet and the first woman to serve as the Oxford Professor of Poetry in the position’s 300-year history.

Her second collection, ‘Dart’ (2002), combines verse and prose and tells the story of the River Dart from a variety of perspectives. Jeanette Winterson called it a ‘… moving, changing poem, as fast-flowing as the river and as deep … a celebration of difference …’.

At the start of the book, Alice notes that the poem ‘is made from the language of people who live and work on the Dart. Over the past two years I’ve been recording conversations with people who know the river. I’ve used these records as life-models from which to sketch a series of characters — linking their voice into a sound-map of the river, a songline from the source to the sea. There are indications in the margins where one voice changes into another. These do not refer to real people or even fixed fictions. All voices should be read as the river’s mutterings.’

The River Dart tells its own story through the voices of the people, whether salmon poacher, naturalist, boat builder, but also industrial workers at a sewage plant and a dairy; a chambermaid, river pilot, ferryman and botanist. Swimmers, town boys, a drowned canoeist, and boats; dead tin miners speak, as well as otters and mythic figures. The cumulative effect brings together human and natural history into a synthesis containing workaday lives, the metaphysical, nature, language and dreams, all to the sounds of the river.

OUR WALK

The River Dart’s name is derived from an ancient word for ‘oak’, and on Day 2 particularly we pass through many oak woods.

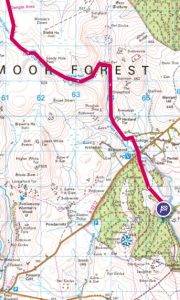

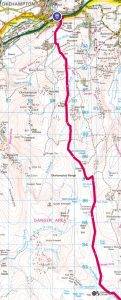

Day 1: The East Dart: Okehampton to Source to Dartmeet

- Distance & Time: 21.8 km (13.6 miles), 6hr 12 mins

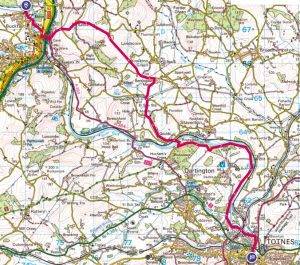

- Map can be found here: Okehampton to Source to Dartmeet

- Terrain: Difficult going, only to be attempted in good weather; wear gaiters and good walking boots, walking poles are helpful, can be very boggy underfoot.

- Startpoint accommodation: stay in Okehampton YHA by the station (not to be confused with Bracken Tor hostel). The Dartmoor Rail line, restored in 2022, provides perfect access. See the timetable here.

Our route starts out along the Old Military Road (check firing times for the Okehampton Danger Area to make sure access is allowed) and is very easygoing for a few miles, with great views in all directions. Just before it crosses over the River Taw close to the Head, we take off south along a barely visible track which gets us close to the Ted Hughes Memorial Stone.

Our route starts out along the Old Military Road (check firing times for the Okehampton Danger Area to make sure access is allowed) and is very easygoing for a few miles, with great views in all directions. Just before it crosses over the River Taw close to the Head, we take off south along a barely visible track which gets us close to the Ted Hughes Memorial Stone.

Ted Hughes and Dartmoor

Ted Hughes moved to the small village of North Tawton a few miles north of Dartmoor in 1961 and lived there for the rest of his life. It has many landscape characteristics in common with his native Yorkshire, including the transitions from farmland to moorland, the powerful streams coming off the moor and their exploitation for power in the early Industrial Revolution. Although, as Alice Oswald observed, in Devon Ted Hughes wrote ‘clay-based poems, whereas previously they’ve been written on millstone grit.’ (there’s a gardener talking)

His house was close to the River Taw, whose source is less than half a mile from the source of the Dart, but heading north to the Bristol Channel rather than south. He loved to walk the moor, and these two rivers gave him the inspiration for a collection of poems called ‘The River’ (1983). ‘River’ celebrates fluvial landscapes, their creatures and their regenerative powers, and was inspired by Hughes’ love of fishing.

When Ted Hughes died in 1998, his ashes were scattered at a private ceremony near Taw Head. He had also expressed a wish that a simple granite stone be engraved with his name and sited near the rising of the Taw. Its exact location is SX 609 865. On it is this simple inscription, from a poem from the collection, the ‘West Dart’:

When Ted Hughes died in 1998, his ashes were scattered at a private ceremony near Taw Head. He had also expressed a wish that a simple granite stone be engraved with his name and sited near the rising of the Taw. Its exact location is SX 609 865. On it is this simple inscription, from a poem from the collection, the ‘West Dart’:

It spills from the Milky Way, pronged with light,

It fuses the flash-gripped earth –

The spicy torrent, that seems to be water

Which is spirit and blood

A recently published book called The Catch: Fishing for Ted Hughes (2022) by Mark Wormald examines in arresting detail the importance of fishing in Ted Hughes’ life. And these two rivers, but especially the Dart, were incredibly important rivers to him in his fishing life. The owner of the fishing rights between Dartmeet and New Bridge (often referred to as the Dart Gorge) gave Ted Hughes rights in perpetuity to fish there and it was one of his very favourite spots. He described this stretch of river as ‘the prettiest and wildest fishing in the West’.

According to Wormald, the powerful poem ‘In the Dark Violin of the Valley’ is set here:

All night a music

Like a needle sewing body

And soul together, and sewing soul

And sky together and sky and earth

Together and sewing the river to the sea.

In the dark skull of the valley

A lancing, fathoming music

Searching the bones, engraving

On the draughty limits of ghost

In an entanglement of stars.

In the dark belly of the valley

A coming and going music

Cutting the bed-rock deeper

To earth-nerve, a scalpel of music

The valley dark rapt

Hunched over its river, the night attentive

Bowed over its valley, the river

Crying a violin in a grave

All the dead singing in the river

The river throbbing, the river the aorta

And the hills unconscious with listening.

Ted Hughes was a huge influence on Alice Oswald, as she recalled in a 2005 lecture that she gave:

‘The first Ted Hughes poem I ever read was “The Horses”. I picked it up one evening after work and I was instantly drawn in. I could feel the poem’s effect physically, as if my braincells had been shaken and woken. When I finished reading (and ever since) the world felt different.

‘So then I read all the Hughes poems I could lay my hands on and what they all had in common was that imaginative grasp of the present – that ability to speak strictly within one moment and not through a misted screen of remembered moments.’

She would certainly have been familiar with his intimacy with The Dart when she came to write her poem. She also compiled ‘A Ted Hughes Bestiary’ (2016), a compilation of his writing about animals real and invented.

The East Dart Valley is one of the most inaccessible parts of Dartmoor and in many ways is the inner heart of the moor. The source, East Dart Head consists of a large bowl that drains a substantial part of high Dartmoor. There are three tributaries that join up and merge at the southern edge of the bowl to form the river.

We came to the conclusion that one should not get too hung up about where the exact source of a river is, as there are so many alternative possibilities. I would draw the analogy to theatregoers who all converge on a single spot for a show, but it is only then they reach the auditorium and the show begins that you can declare them to be a theatre audience. So it is with water, it’s not until it congregates together into a body that it’s really of any significance and can be given a name.

We came to the conclusion that one should not get too hung up about where the exact source of a river is, as there are so many alternative possibilities. I would draw the analogy to theatregoers who all converge on a single spot for a show, but it is only then they reach the auditorium and the show begins that you can declare them to be a theatre audience. So it is with water, it’s not until it congregates together into a body that it’s really of any significance and can be given a name.

I love the way the poem opens with Alice Oswald describing ‘one of us’ making just the journey we have just made (fortunately as you can see we were blessed with perfect weather, and yes I was carrying a spare pair of socks):

‘Who’s this moving alive over the moor?

An old man seeking and finding a difficulty.

Has he remembered his compass his spare socks

does he fully intend going in over his knees off the

military track from Okehampton?keeping his course through the swamp spaces

and pulling the distance around his shouldersand if it rains, if it thunders suddenly

and all that lies to hand is his own bones?Tussocks, minute flies,

wind, wings, rootsHe consults his map. A huge rain-coloured wilderness.

This must be the stones, the sudden movement,

the sound of frogs singing in the new year.

Who’s this issuing from the earth?The Dart, lying low in darkness calls out Who is it?

trying to summon itself by speaking …’

The walker replies:

An old man, fifty years a mountaineer, until my heart gave out,

so now I’ve taken to the moors. I’ve done all the walks, the Two

Moors Way, the Tors, this long winding line the Dart

this secret buried in reeds at the beginning of sound I

won’t let go man, under

his soakaway ears and his eye ledges working

into the drift of his thinking, wanting his heart

I keep you folded in my mack pocket and I’ve marked in red

where the peat passes are the the good sheep tracks

cow-bones, tin-stones, turf-cuts.

listen to the horrible keep-time of a man walking,

rustling and jingling his keys

at the centre of his own noise,

clomping the silence in pieces and I

I don’t know, all I know is walking. Get dropped off the military

track from Okehampton and head down into Cranmere pool.

It’s dawn, it a huge sphagnum kind of wilderness, and an hour

in the morning is worth three in the evening. You can hear

plovers whistling, your feet sink right in, it’s like walking on the

bottom of a lake.

What I love is one foot in front of another. South-south-west and

down the contours. I go slipping between Black Ridge and White

Horse Hill into a bowl of moor where echoes can’t get out

Alice Oswald describes the moment of discovery of the source very evocatively:

Alice Oswald describes the moment of discovery of the source very evocatively:

‘and I find you in the reeds, a trickle coming out of a bank, a foal of a river

one step-width water

of linked stones

trills in the stones

glides in the trills

eels in the glides

in each eel a fingerwidth of sea’

A couple of kilometres south of here three tributaries join up to create a much more definable flow, and the day we walk here the exact spot is marked by a Dartmoor pony placidly grazing and its foal (cf. foal of a river). In all the time it takes us to reach where they are standing they don’t move an inch.

A couple of kilometres south of here three tributaries join up to create a much more definable flow, and the day we walk here the exact spot is marked by a Dartmoor pony placidly grazing and its foal (cf. foal of a river). In all the time it takes us to reach where they are standing they don’t move an inch.

Soon after the tributaries, we reach Sandy Hole, a popular place for wild swimming. We immediately comment that the narrow, well-defined channel looks almost man-made and it turns out we are right. This is where ‘tinners’ plied their trade hundreds of years ago, channelling the river to increase its flow in order to ‘stream’ water over the tin deposits to separate them from waste materials.

Soon after the tributaries, we reach Sandy Hole, a popular place for wild swimming. We immediately comment that the narrow, well-defined channel looks almost man-made and it turns out we are right. This is where ‘tinners’ plied their trade hundreds of years ago, channelling the river to increase its flow in order to ‘stream’ water over the tin deposits to separate them from waste materials.

There are several examples of tinners’ huts and spoil heaps in this area and we pause to admire a ‘Beehive Hut’, built to store their tools and as a shelter.

Our next stop is the East Dart Waterfall, a veritable beauty spot with an unusual curtain of water falling diagonally down a seven-foot drop, and then rushing over a series of large ledges to a pool below.

Our next stop is the East Dart Waterfall, a veritable beauty spot with an unusual curtain of water falling diagonally down a seven-foot drop, and then rushing over a series of large ledges to a pool below.

The right angle of the river we see on our way downstream just after the island is yet further evidence as to how much the direction and nature of the flow were reconfigured by the tinners in pursuit of their precious metal.

We are starting to tire now, but the path is well marked and of course downhill all the way (surely no one would choose to do sea to source?!).

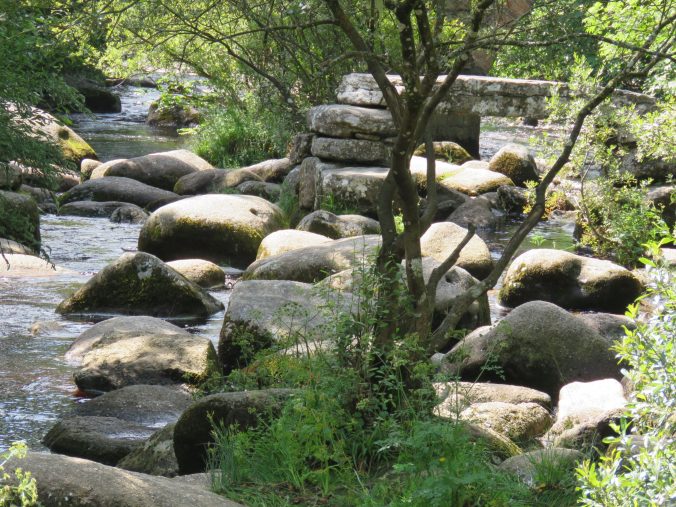

In an hour or so we reach Postbridge, and pause at the Clapper Bridge, one of the best-preserved clapper bridges in the country, thought to have been built in the thirteenth century to enable pack horses carrying tin to cross. The word ‘clapper’ derives from an Anglo-Saxon word, cleaca, meaning ‘bridging the stepping stones’.

In an hour or so we reach Postbridge, and pause at the Clapper Bridge, one of the best-preserved clapper bridges in the country, thought to have been built in the thirteenth century to enable pack horses carrying tin to cross. The word ‘clapper’ derives from an Anglo-Saxon word, cleaca, meaning ‘bridging the stepping stones’.

We are rather exhausted by our travails across the moor and head for the village stores for an ice cream and cold drink. Whose silly idea was it to push onto Bellever Youth Hostel for the night (mine:) Anyway, the final two miles or so are pleasantly straightforward, and it turns out to be a very friendly hostel, with the usual unusual mix of hostellers – a large Hell’s Angel biker group on the last night of their tour, a young French family and of course our motley crew.

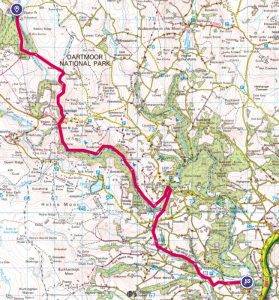

Day 2: The Upper Dart: Bellever to Buckfastleigh

- Distance & Time: 18 km (11.25 miles), 5 hrs 6mns

- The map can be found here: Dartmeet to Buckfastleigh

- Terrain: Difficult going, no defined path from Dartmeet to the New Bridge, but a very rewarding route nonetheless.

We set out early from YHA Bellever and walk down the road with a stream on our right guiding us back to the main river. We have lost count of the number of tributaries we mingle with on our journey, it is a reminder that a river is fed from myriad sources. Each stream in the hilly country has a sense of urgency to be repatriated with ‘The Mother Ship’, the River Dart. We admire the clapper bridge in the early sun and then start heading downstream alongside a delightful pine forest.

We set out early from YHA Bellever and walk down the road with a stream on our right guiding us back to the main river. We have lost count of the number of tributaries we mingle with on our journey, it is a reminder that a river is fed from myriad sources. Each stream in the hilly country has a sense of urgency to be repatriated with ‘The Mother Ship’, the River Dart. We admire the clapper bridge in the early sun and then start heading downstream alongside a delightful pine forest.

Fairly soon we reach Dartmeet, where the East and West Dart rivers join up on their way to the sea to become an altogether bigger and broader river.

‘Dartmeet – a mob of waters

where East Dart smashes into West Dart

two wills gnarling and recoiling

and finally knuckling into balance

in that brawl of mudwaves

the East Dart speaks Whiteslad and Babeny

the West Dart speaks a wonderful dark fall

from Cut Hill through Wystman’s Wood

put your ear to it, you can hear water

cooped up in moss and moving

slowly uphill through lean-to trees

where every day the sun gets twisted and shut

with the weak sound of the wind

rubbing one indolent twig upon another

and the West Dart speaks roots in a pinch of clitters

the East Dart speaks coppice and standards.’

This next phase of the walk is truly remarkable and, although the path is sometimes hard to find and full of boulders and tree roots, providing you are careful with your footing everything will be fine as all you need to do is keep the river on your right. I carried a walking pole, which helped enormously.

This next phase of the walk is truly remarkable and, although the path is sometimes hard to find and full of boulders and tree roots, providing you are careful with your footing everything will be fine as all you need to do is keep the river on your right. I carried a walking pole, which helped enormously.

We feel we are intruding upon Alice Oswald’s canoeist’s experience:

‘But what I love is midweek between Dartmeet and Newbridge; kayaking down some inaccessible section between rocks and oaks in a valley gorge which walkers can’t get at. You’re utterly alone.’

And now the river is talking once again:

‘the way I talk in my many-headed turbulencer

among these modulations, this nimbus of words kept in motion

sing-calling something definitely human,

will somebody sing this riffle perfectly as the invisible river

sings it…’

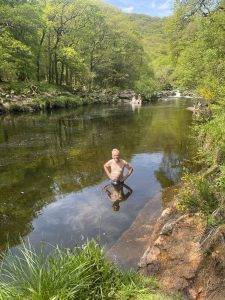

Sharrah Pool is a popular swimming spot, and the author was persuaded (by himself) to briefly go in.

Sharrah Pool is a popular swimming spot, and the author was persuaded (by himself) to briefly go in.

Luckey Tor is a huge granite tor that suddenly looms out of the undergrowth. Dartmoor expert Eric Hemery described it thus: ‘This lofty riverside bastion with a bold, light-coloured facade was a natural watch-tower for the confederates of those who were poaching, smuggling or sheep-rustling under the concealment of the heavily wooded sides of the gorge’.

Luckey Tor is a huge granite tor that suddenly looms out of the undergrowth. Dartmoor expert Eric Hemery described it thus: ‘This lofty riverside bastion with a bold, light-coloured facade was a natural watch-tower for the confederates of those who were poaching, smuggling or sheep-rustling under the concealment of the heavily wooded sides of the gorge’.

Once we get to New Bridge we cut back up the slope on the far side of the river towards Holne.

Once we get to New Bridge we cut back up the slope on the far side of the river towards Holne.

There is a very friendly community stores and tea rooms here. Re-invigorated, we find the route to Buckfastleigh straightforward and charming, joining the Dartmoor Way High-Moor link, a route linking Buckfastleigh and Tavistock. We especially like the bit alongside Holy Brook. Perhaps the stream’s name gives us a clue that it passes through the grounds of Buckfast Abbey before it joins the River Dart, or perhaps because of its legendary powers of alleviating strained muscles, bruises and rheumatism by wading in its waters – could be useful for tired walkers!

We soon arrive at Northgate House alongside the abbey, offering impeccable, good-value accommodation and a hearty breakfast. it is part of the Foundation.

Buckfast Abbey forms part of an active Benedictine monastery. Buckfast first became home to an abbey in 1018, but became a ruin and then a quarry after the Dissolution. The building we admire today was completed in 1938 and is once again an active Benedictine foundation, with 13 monks. The monastery’s most successful product is Buckfast Tonic Wine, commonly known as Buckie, a fortified wine that the monks began making in the 1890s – although in recent years it has become rather notorious due to its perceived links to violent anti-social behaviour.

Buckfast Abbey forms part of an active Benedictine monastery. Buckfast first became home to an abbey in 1018, but became a ruin and then a quarry after the Dissolution. The building we admire today was completed in 1938 and is once again an active Benedictine foundation, with 13 monks. The monastery’s most successful product is Buckfast Tonic Wine, commonly known as Buckie, a fortified wine that the monks began making in the 1890s – although in recent years it has become rather notorious due to its perceived links to violent anti-social behaviour.

Day 2: Alternative Route

Purists will have noticed that we left the River Dart at New Bridge as there are no public footpaths that take you downstream along the river from there to Buckfastleigh.

I am of course a purist and did some research on what might be possible. First of all, I emailed the owners of Holne Chase to ask permission to walk along their river track from just after Holne Bridge, which they very kindly gave. This route was a delight and very easy to follow once through the (private) entrance gates. For the next stage through the River Dart Country Park, we had each bought day passes to give us (legal) access, but sticking to the river proved much more challenging (enough said).

I am of course a purist and did some research on what might be possible. First of all, I emailed the owners of Holne Chase to ask permission to walk along their river track from just after Holne Bridge, which they very kindly gave. This route was a delight and very easy to follow once through the (private) entrance gates. For the next stage through the River Dart Country Park, we had each bought day passes to give us (legal) access, but sticking to the river proved much more challenging (enough said).

The final stage alongside the river through Hembury Woods was straightforward as this is National Trust land. We then followed the small road into Buckfastleigh over Holy Brook. Would we do it again?! Probably not because of the difficulties presented by the Country Park, but these things have to be done once…

Day 3: The Middle Dart: Buckfastleigh to Totnes

- Distance & Time: 14.2 km (8.9 miles), 4 hrs 1mns

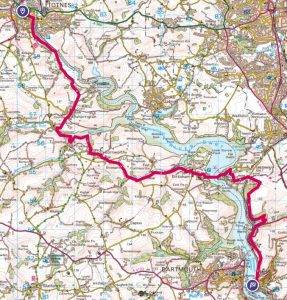

- Map: The Middle Dart: Buckfastleigh to Totnes

- Terrain: A much easier day, giving you time to explore beautiful Totnes

From Buckfastleigh to Staverton there is no option along the river, so we elect instead to go up into the rolling Devon hills, which proves to be a lovely contrast to the wooded valley of the Dart. We then re-connect with the River Dart at Staverton and then are able to walk alongside the river all the way to Totnes.

The alternative, which is also great fun, is to take the steam train from Buckfastleigh to Staverton, which runs right alongside the river all the way. The only drawback is that the first train is not until mid-morning. You can check running times here.

The alternative, which is also great fun, is to take the steam train from Buckfastleigh to Staverton, which runs right alongside the river all the way. The only drawback is that the first train is not until mid-morning. You can check running times here.

Anyway, from Staverton, we cross  the ancient bridge and quickly find a route into the huge grounds (1,2000 acres) of Dartington Hall, where walkers are made to feel most welcome; and follow a path alongside the river that takes us all the way to the outskirts of Totnes.

the ancient bridge and quickly find a route into the huge grounds (1,2000 acres) of Dartington Hall, where walkers are made to feel most welcome; and follow a path alongside the river that takes us all the way to the outskirts of Totnes.

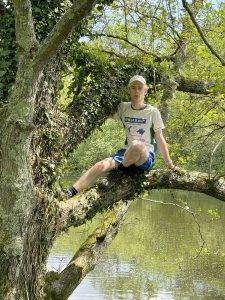

Dartington Hall is a fascinating and friendly place, delivering progressive learning programmes in the arts, ecology and social justice. We keep coming upon clusters of students involved in ardent debate, it feels just like being back at university. The estate looks after the grounds most beautifully, we are in a state of near ecstasy as we walk through on a fine May day, there is so much nature to enjoy here.

Dartington Hall is a fascinating and friendly place, delivering progressive learning programmes in the arts, ecology and social justice. We keep coming upon clusters of students involved in ardent debate, it feels just like being back at university. The estate looks after the grounds most beautifully, we are in a state of near ecstasy as we walk through on a fine May day, there is so much nature to enjoy here.

Just after Riverford Bridge, there is a weir with three channels of water, and I think this is what Alice Oswald is describing here;

‘whenever currents of water meet the confluence is

always the place

where rhythmical and spiralling movements may arise,

spiralling surfaces which glide past one another in

manifold winding and curving forms

new water keeps flowing through each single strand of

water

whole surfaces interweaving spatially and flowing past

each other

in surface tension, through which water strives to attain

a spherical drop-form’

And then we pass Still Copse Pool, where the swimmer recounts:

And then we pass Still Copse Pool, where the swimmer recounts:

‘We jump from a tree into a pool, we change ourselves

into the fish dimension. Everybody swims here

under Still Pool Copse, on a Saturday,

slapping the water with bare hands, it’s fine once you’re in’

As the path skirts around the industrial estate of Totnes, it feels decidedly less salubrious, but it’s worth it to make sure you come out at Totnes Bridge, so you can start at the  bottom of the High St, walk all the way up and enjoy this cornucopia of independent shops and eating places to the full.

bottom of the High St, walk all the way up and enjoy this cornucopia of independent shops and eating places to the full.

We are lucky enough to be staying at the Bull Inn (owned by the founders of Riverford Organics) at the top and later explore Totnes Castle with its glorious views. To cap everything, Sam and Pedro find a CD recording of The River Dart by no less than Alice Oswald herself and give it to me as a gift for organising the holiday (really enjoyed listening to it a few days later.)

We are lucky enough to be staying at the Bull Inn (owned by the founders of Riverford Organics) at the top and later explore Totnes Castle with its glorious views. To cap everything, Sam and Pedro find a CD recording of The River Dart by no less than Alice Oswald herself and give it to me as a gift for organising the holiday (really enjoyed listening to it a few days later.)

Day 4: The Lower Dart: Totnes to Dartmouth along the Dart Valley Way

- Distance & Time: 19.6 km (12.2 miles), 5 hours 56 mins

- Find the map online here: Totnes to Dartmouth along the Dart Valley Way

- Terrain: Well-marked route, easy going

- Ferry at Dittisham, if you want to take in Agatha Christie’s Greenway House too.

The river becomes tidal at Totnes (‘the river meets the Sea at the foot of Totnes Weir’) and its character changes – rolling downs, much longer vistas, a sense that the sea cannot be far away.

The river becomes tidal at Totnes (‘the river meets the Sea at the foot of Totnes Weir’) and its character changes – rolling downs, much longer vistas, a sense that the sea cannot be far away.

‘why is this flickering water

with its blinks and side-long looks

with its language of oaks

and clicking of its slatey brooks

why is this river not ever

able to leave until it’s over?’

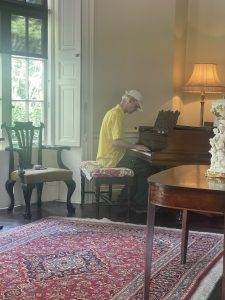

We cross over on the Dittisham Ferry to look at Agatha Christie’s house at Greenway (NT), the gardens are an absolute joy to walk around and they let Sam play Agatha’s piano (she had nearly become a concert pianist, but was apparently too overcome by nerves to perform in public).

We cross over on the Dittisham Ferry to look at Agatha Christie’s house at Greenway (NT), the gardens are an absolute joy to walk around and they let Sam play Agatha’s piano (she had nearly become a concert pianist, but was apparently too overcome by nerves to perform in public).

After lunch here, we then continue on the east bank to Kingsbridge. As we reach the estuary, the ferryman speaks:

‘Dartmouth and Kingsweir –

two worlds, like two foxes in a wood,

and each one can hear the wind-fractured

closeness of the other.’

We have arrived, presumably, long after the water we saw arise at the source, but undoubtedly wiser about life than when we began.

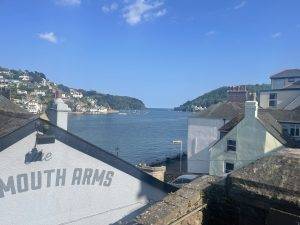

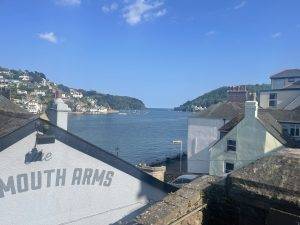

We spent our last night in the Nelson suite of the Bayards Cove Inn, which has great views over the rooftops down to the estuary and the sea.

We spent our last night in the Nelson suite of the Bayards Cove Inn, which has great views over the rooftops down to the estuary and the sea.

OTHER STUFF

- Read: this brilliant blog by Katherine Venn – https://www.caughtbytheriver.net/explore/tags/walking-the-river-dart-column

- Read: ‘The River Dart’ (1951) by Ruth Manning-Sanders on the river and its history

- Read: ‘Walking the Dartmoor Waterways: A Guide to Retracing the Leats and Canals of Dartmoor Country’ (1986), by Eric Hemery

- Read: ‘The Catch: Fishing for Ted Hughes’ (2022) by Mark Wormald – lots on the Dart.

- Read: ‘The Flow’ (2022) by Amy-Jane Beer. Chapter 9 is about the Dart.

- Buy: the children’s book by the Two Blondes called ‘Dart the River’ (2015), which recounts the story of the River Dart from its source to the sea.

Leave a Reply