‘My bedroom window in that house still operates as a lens and framing device’

‘A border area where habitation meets the uninhabitable’

The book that inspired this walk – The Marsden Poems (2020)

I read a review of this collection of poems in the Sunday Times just as I was starting to compile the list of literary walks that I wanted to undertake. I couldn’t believe my luck. A writer who had decided it would be helpful to show on a map exactly where each poem is set.

And a proper map too, more or less to scale, not like those whimsical Swallows & Amazons maps that combine fact and invention so seamlessly. And not with slightly altered place names that Thomas Hardy and DH Lawrence amongst others liked to concoct, which make me want to shout out ‘I know it’s Dorchester/Eastwood, please don’t confuse me!’ No, Marsden in the collection is the very same Marsden as in real life. For us nerdy types who like an absolute sense of place, this is perfect.

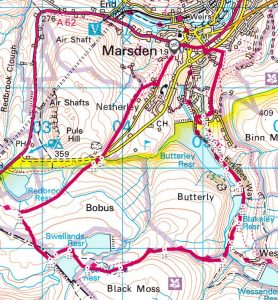

This picture shows the map in all its glory on the front pages of the book.

KEY DATA

- Terrain: pavement and rugged moor on well-defined paths

- Starting point: Old Mount St, HD7 6DX

- Distance: 10 km (6.2 miles)

- Walking time: 3 hrs 6 mins

- OS Map: OL21: South Pennines. The map can also be found online at: https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/9888707/Marsden-West-Yorkshire

- Facilities: Food, toilets in Marsden

SIMON ARMITAGE (1963-)

Marsden is Simon Armitage’s muse just as the Lake District was Wordsworth’s. He was born and brought up here, and today only lives about six miles away. To mark the significance of the place to his creativity, in 2020 he published ‘Magnetic Field, The Marsden Poems’, a collection of work about Marsden over the years – the magnetic field that keeps drawing him back.

Marsden is Simon Armitage’s muse just as the Lake District was Wordsworth’s. He was born and brought up here, and today only lives about six miles away. To mark the significance of the place to his creativity, in 2020 he published ‘Magnetic Field, The Marsden Poems’, a collection of work about Marsden over the years – the magnetic field that keeps drawing him back.

‘Marsden was an extraordinary adventure playground for a child, with its system of switchbacks, towpaths and unadopted roads, and with its many reservoirs, like a sleeping pantheon of water deities above our heads, whose names became a recited litany of localness and belonging among those in the know.’

Place and landscape are especially important to Simon Armitage. He studied geography at university, and his first poetry collection was called Human Geography (1988). There are lots of geographer’s references in his works – true north, magnetic fields, compasses, Roman roads etc. He wrote ‘Walking Home’ (2012), an account of his walk along the Pennine Way, ending up at Marsden. And he wrote physically onto the landscape in ‘Stanza Stones’ (2013), a series of poems on the subject of rainfall, carved into rock faces between Marsden and Ilkley.

He said: ‘I’m very aware of the surroundings I grew up in and the kind of impression they made on me. I’m very spatially aware…the longer I’ve stayed there, I’ve felt as if I’ve located a kind of visionary magic in the landscape.’

‘I’ve come to feel that there is something genuinely unique about this transcendent and transgressive location: a border area where habitation meets the uninhabitable; where Yorkshire meets Lancashire (not just topographically, but culturally); where the land disappears into the sky on many days of the year; where the last lawn is separated from the moor by the dividing line of a privet hedge; where roads peter out into cart-tracks and bridleways.’

He is determined that writing about the environment, ‘the issue of our time’, will be at the heart of his 10-year tenure as Poet Laureate (2019-2029). ‘Nature has very much come back into the centre of what poetry can, and should, be dealing with.’

Armitage is proud of being a ‘no brow’ poet. ‘I’ve always been a kitchen sink poet,’ he told Melvyn Bragg. What I like about his poetry is that it makes quite a bit of sense even the first time you read it… but he kind of cheats with the adage ‘only write what you know about’ because, although he certainly manages that, he expands in the blink of an eye out to the universal.

THE WALK

We begin where it all began, Simon Armitage’s birthplace, at 27 Old Mount Rd.

We begin where it all began, Simon Armitage’s birthplace, at 27 Old Mount Rd.

‘The family home was a small end-terrace on the side of the hill, and despite not living there for 30 years my bedroom window in that house still operates as a lens and framing device. I’d lie in bed watching the nocturnal comings and goings in the streets below, even keeping a logbook of activity as people spilled out from the pub at closing time and articulated lorries pulled up for the night in the area of wasteland opposite the New Inn. The evidence of all kinds of skulduggery is probably set down in those pages, though recorded in innocence.’

‘Even in Marsden the extraordinary could happen, apparently. Staring out of that window every night I developed a new sense of the world, one that went beyond the factual and the informational. A sense of what it was like, and how it felt. That was the beginning of my life as a writer…’

‘(A few years later) I was a geography graduate with a head full of theories about people and places. So the village became the drawing board or board game on which I could practise my poetics and play out my perspectives. The frame of the window might have operated as a limiting device, restricting my perception of the wider world, but it was an invaluable template for bringing focus to the poems and legitimising the use of local subjects and vernacular in a poetic context.’

We can just see this very window from our vantage point, and the privet hedge at the bottom of the garden that he writes about in ‘Privet’ (12):

‘…And because I’d done wrong I was sent

to the end of the garden to cut the hedge,

that dividing line between moor and lawn’

We notice that the garden wall in front of us running alongside the house seems to have been hastily constructed with breeze blocks, and his poem ‘After the Hurricane’ (66) seems to explain why:

‘Some storm that was, to shoulder-charge the wall

In my old man’s backyard and to knock it flat.’

Then we head down from the house to the main street and recall ‘Zoom’ (45):

‘It begins as a house, an end terrace

in this case

but it will not stop there. Soon it is

an avenue

which cambers arrogantly past the Mechanics’ Institute,

turns left

at the main road without even looking

and quickly it is

a town with all four major clearing banks,

a daily paper

and a football team pushing for promotion.’

I love the physical rush of this poem, rather like a tyre as we accelerate into the town.

We reach the bottom of the road and gaze diagonally left towards St Bartholomew’s Church where Armitage had been a chorister, and which he writes about in a truly Hardy-esque fashion in ‘Harmonium’ (79):

‘But its hummed harmonics still struck a chord:

for a hundred years that organ had stood

by the choristers’ stalls, where father and son,

each in their time, had opened their throats

and gilded finches – like high notes – had streamed out.’

We turn right and soon pass the distinctive frontage of the Old Marsden Fire Station, opposite Packhorse Court, which dates from 1909. Armitage wrote about it in ‘Emergency’ (80):

‘The makeshift crew

were volunteer part-timers:

butchers, out-menders,

greasy perchers and hill-farmers

who’d pitch up in bloody aprons,

boiler suits or pyjamas

then venture forth,

fire-slaying on the tender.’

We passed the big plain frontage of The New Inn, which he mentions in ‘True North’ (28), a poem about homecoming and what makes us who we are:

‘In the Old New Inn two men sat locked

In an arm-wrestle – their one combined fist

Dithered like a compass needle.’

Armitage attended Marsden Junior School, as recalled in ‘The Shout’ (11):

‘We went out

into the school yard together, me and the boy

whose name and faceI don’t remember. We were testing the range

of the human voice:

he had to shout for all he was worthI had to raise an arm

from across the divide to signal back

that the sound had carried.’

One can finish the walk here and perhaps walk back into the centre of town, but we choose a moors excursion that takes us to one of Armitage’s favourite childhood spots.

One can finish the walk here and perhaps walk back into the centre of town, but we choose a moors excursion that takes us to one of Armitage’s favourite childhood spots.

‘I grew up partly on the moors, these big open spaces, and they seemed to be places where anything could happen, or where you could imagine anything could happen. There was never anybody there, so they were yours for the taking, really, especially when you wrote about them.’

We reach the Black Moss reservoir, referenced in one of his finest poems ‘It Ain’t What You Do It’s What It Does to You’ (42):

‘But I… skimmed flat stones across Black Moss on a day

so still I could hear each set of ripples

as they crossed. I felt each stone’s inertia

spend itself against the water; then sink.’

He talks about the poem: ‘It’s a sort of manifesto – it’s like an Ars Poetica for me. It addresses that issue – it says that you don’t have to have great subjects in mind to write well. Part of my philosophy has always been to try to find the (for want of a better word) miraculous within the everyday and the ordinary and the domestic.’

Descending from the moor, we reach the point where ‘The Tyre’ (21) picked up speed:

‘We bullied it over the moor, drove it,

pushed from the back or turned it from the side,

unspooling a thread in the shape and form

of its tread, in its length, and in its line,

rolled its weight through broken walls, felt the shock

when it met with stones, guided its sleepwalk

down to meadows, fields, onto level ground…

…Once on the road it picked up pace, free-wheeled,

then moved up through the gears, and wouldn’t give

to shoulder-charges, kicks;’

Finally, we are back at his childhood home once again (our mini-zoom is over), and perhaps it is most fitting to end with an excerpt from ‘Mother, any distance greater than a single span’ (46), a metaphor for the enduring strength of the relationship between a mother and their child, the measuring tap a metaphor for the umbilical cord, the very other end of the zoom.

‘You at the zero-end, me with the spool of tape, recording

length, reporting metres, centimetres back to base, then leaving

up the stairs, the line still feeding out, unreeling

years between us. Anchor. Kite.’

This walk makes us feel we have grown up in Marsden ourselves and think about many aspects of our own everyday lives.

OTHER STUFF

Buy The Book: Simon Armitage, ‘Magnetic Fields, The Marsden Poems’ – indispensable for this walk. We read the poems in full as we went around.

Listen to: Simon Armitage reading some of the Marsden poems at www.simonarmitage.com/magnetic-field-the-marsden-poems/

Follow: The Stanza Stones Trail, a 47-mile walking route from Marsden to Ilkley, along the Pennine watershed, linking six poems by Simon Armitage which have been carved into stone. Download a full guide at: http://www.ilkleyliteraturefestival.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Stanza-Stones-Trail-Guide.pdf

Attend: The October Marsden Jazz Festival, https://www.marsdenjazzfestival.com/

Leave a Reply