‘Glasgow is a magnificent city,’ said McAlpin. ‘Why do we hardly ever notice that?’

‘Morgan saw Glasgow. A city with a great big heart; a city of opposites.’

The Inspiration for this walk: Edwin Morgan’s Glasgow Sonnets (1972)

To be completely honest I knew none of the Glasgow writers until I started planning a trip to Glasgow and realised I needed to get reading. And I have been completely blown away by what I have discovered, directness of communication, fierce independence of thought and a playful love of language.

Of all the books I bought, perhaps this thin volume of the Glasgow Sonnets by Edwin Morgan was the one I love the most, numbered and signed.

KEY DATA

- Terrain: pavements and several slopes

- Starting point: Royal Exchange Square, G1 3AJ

- Distance: 16.8 km (10.6 miles)

- Walking time: 4 hrs 37 mins

- OS Map: https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/11473886/Glasgow-Scotland-Glasgows-modernist-writers

- Facilities: all city facilities

THE WRITERS

What these twentieth and twenty-first-century Glasgow writers all have in common is breaking free from tradition, breaking through to new freedoms…political and spiritual independence, the power of nature, choices on sexuality; and ultimately helping re-define Glasgow as a great independent, post-empire city.

Jackie Kay (1961-

Jackie Kay was born in Edinburgh to a Scottish mother and a Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple and grew up in Bishopbriggs, a suburb of Glasgow. Her adoptive father worked for the Communist Party full-time, and her adoptive mother was the Scottish secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – so she always had a different perspective on the world.

Jackie Kay was born in Edinburgh to a Scottish mother and a Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple and grew up in Bishopbriggs, a suburb of Glasgow. Her adoptive father worked for the Communist Party full-time, and her adoptive mother was the Scottish secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – so she always had a different perspective on the world.

Jackie reflected: ‘People often ask me where I’m from, even in my own country – I seem to have a whole collection of strange anecdotes of people doing that. I’m going to sit down in a pub on a chair in London and this woman went “You cannae sit in that chair. It’s my chair.” And me saying to her, “Oh right, you’re from Glasgow aren’t you?” And she says, “Aye, how did you know that?” And I said, “I’m from Glasgow myself,” and she went, “You’re not are you? You foreign looking bugger!” So that kind of thing happens a lot, and it happens so often I decided I’d just write a poem about being black and Scottish.’ That poem was ‘In my Country’.

She decided to concentrate on writing after Alasdair Gray read her poetry and told her that writing was what she should be doing. She came onto the literary stage with the publication of The Adoption Papers, published in 1991, a multiply-voiced collection of poetry that deals with identity, race, nationality, gender, and sexuality from the perspectives of three women: an adopted bi-racial child, her adoptive mother, and her biological mother. She also went on to write a number of novels, including ‘Trumpet’ (1998):

‘Glasgow appears in the novel in lots of different ways and I mean I love Glasgow as a city and I grew up in Glasgow and it’s a great city to write about, in the kind of tangible way. It’s fascinating to me, endlessly fascinating to me to try and find different ways to write about Glasgow.’

In 2016, Kay became the Scots Makar (National Poet of Scotland).

Denise Mina (1966-)

Denise Mina is a crime writer and playwright. She wrote the Garnethill trilogy, set in the Garnethill region of the city, featuring the character of Patricia ‘Paddy’ Meehan, a Glasgow journalist.

Mina left school at 16 and worked in a variety of jobs, including as a barmaid, kitchen porter and cook. In her twenties, she worked in auxiliary nursing for geriatric and terminal care patients, before returning to education and earning a law degree from The University of Glasgow.

Edwin Morgan (1920-2010)

Edwin Morgan is widely recognised as one of the foremost Scottish poets of the twentieth century.

He taught English at Glasgow University all his working life and became the city’s first Poet Laureate in 1999. He became Scotland’s laureate too, in 2004 – its first Makar or national poet. He loved Glasgow, the city of his birth, for its energy, industrial inventiveness, humour and crowded streets.

Jackie Kay wrote about him: ‘He had a boyish curiosity and fascination for everything. His series of Glasgow Sonnets are among my favourite of his poems. He writes about the city so well and many of his poems, like From A City Balcony, capture that view. Morgan saw Glasgow. A city with a great big heart; a city of opposites.’

Alasdair Gray (1934-2019)

Alasdair Gray, a lifelong socialist and Scottish nationalist, was born and lived in Glasgow all his life. According to biographer Gavin Miller, he ‘played a central role during the nineteen-eighties and nineteen-nineties in reimagining literary Glasgow, and largely bypassing all those tired clichés of gangs, hard men, and knife violence.’

His 1981 debut novel, Lanark, is widely seen as a landmark in Scottish literature, a 600-page epic interlacing realist sections set in Glasgow with satirical fantasy set in a parallel city called Unthank, written in four books and starting with book three. Gray said about his work ‘It’s as much documentary work I suppose as Dickens documents London.’

His 1981 debut novel, Lanark, is widely seen as a landmark in Scottish literature, a 600-page epic interlacing realist sections set in Glasgow with satirical fantasy set in a parallel city called Unthank, written in four books and starting with book three. Gray said about his work ‘It’s as much documentary work I suppose as Dickens documents London.’

The front cover of the novel is a visual ode to the city, with its Royal Infirmary cupolas and Victorian Great Western Road, its Blackhill kids and the Clyde widening out to the sea, a breathing, many-layered Glasgow that was not just an industrial warehouse for ships, but a resonant and fully claimed city that could stand for the entire nation.

‘Glasgow is a magnificent city,’ says the character McAlpin. ‘Why do we hardly ever notice that?’ ‘Because nobody imagines living here,’ said Thaw… ‘Think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.’ Gray in his artistic and literary output did a huge amount to alter this perception. It could be said that in many ways Lanark had the same effect on the perception of Glasgow as Ulysses did on Dublin, albeit it has never sold anywhere near as many copies.

OUR WALK

We start outside the Gallery of Modern Art in Royal Exchange Square, by the statue of the Duke of Wellington with a traffic cone on his head. This sets the tone of irreverence that we find throughout our day. Glaswegians have a fierce sense of independence and their own brand of humour.

Glasgow Central Station

Jackie Kay’s ‘Glasgow Snow’, a poem about an Ethiopian seeking sanctuary, opens in the spot we are just passing:

‘You were found in the snow in Glasgow

Outside the entrance to Central Station.

But when you were sent here, Glasgow,

In the dead winter: below zero, no place to go,

You rode the buses to keep warm: X4M, Toryglen,

Castlemilk, Croftfoot, Carbrain, Easterhouse,

Moodiesburn, Red Road Flats, Springburn,

No haven, no safe port, no support,

No safety net, no sanctuary, no nothing.

Until a girl found you in the snow, frozen,

And took you under her wing, singing.’

We wend our way up the eighteenth-century grid system and across Sauchiehall St, a wide shopping street, where Edward Morgan’s poem, ‘Glasgow 5 March 1971’ was set. It is a rather gruesome description of a robbery by two youths who push an unsuspecting couple through a shop window, with an Auden-esque twist at the close:

‘…The two youths who have pushed them

are about to complete the operation

reaching into the window

to loot what they can smartly.

Their faces show no expression.

It is a sharp clear night

in Sauchiehall Street.

In the background two drivers

keep their eyes on the road.’

Ross St

Jackie Kay set part of her very first novel, ‘Trumpet’, right here on Rose Street. Her first novel, it deals with the relationship between a very famous jazz musician called Joss and his wife Millie; Millie’s flat was on Rose Street in Garnethill and it was where they first met and where their relationship blossomed.

‘He walks me to my flat in Rose Street, Number 14. And leaves me. ‘I know where you are now,’ he says. A little kiss on my cheek. I get in and throw myself on my bed, punch my pillow. Then I stroke the side of my cheek Joss Moody kissed and say, courting to myself, courting, courting, courting until it sounds like a beautiful piece of music.’

Jackie says of the book: ‘So I wanted to place Joss Moody and Millie in Glasgow where they meet and Millie has a flat in Rose Street, just near where the GFT (Glasgow Film Theatre) is, just near the art college. I quite liked the idea of her living in a steep street like that. I like how hilly Glasgow is, how San Francisco Glasgow is.’

The Glasgow School of Art

The Glasgow School of Art is tragically a burnt-out wreck at the moment. Progress to reinstate the building has been painfully slow, with a completion date of around 2030 currently projected.

The Mack has had many distinguished students who have gone on to become published writers, including Alasdair Gray, Henry Hellier and Liz Lochhead.

Objects from the school’s archives can be seen at the permanent exhibition in the Window on Mackintosh visitor centre on Sauchiehall St, where you can also learn about the school’s most famous student, the architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Hill St

We continue to 101 Hill Street. Author and journalist Catherine Carswell (1879–1946) was born here. She worked as a critic for many years but was fired from the Glasgow Herald for her favourable review of DH Lawrence’s ‘The Rainbow’. ‘Open the Door’ (1920), the first of two Glasgow-based novels, dealt with the quest for independence of a heroine who attends the Glasgow School of Art, as she did. A lively, unsentimental biography of Burns outraged traditionalists, to the extent she received a bullet in the post. But she remains perhaps best known for her biography of DH Lawrence, The Savage Pilgrimage (1932), which also caused quite a kerfuffle and was not published in its unfiltered version until 1981.

Scott St

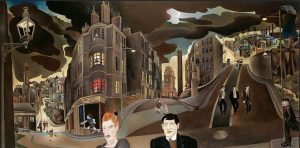

Garnethill, by Alasdair Gray

Denise Mina’s gritty crime thriller trilogy, Garnethill, is also set in the area around the art school. The central protagonist of the trilogy, Maureen O’Donnell, lives in a top-floor tenement flat at 56 Buckleigh St, just off Scott St.

‘Maureen dried her eyes impatiently, lit a cigarette, walked over to the bedroom window and threw open the heavy red curtains. Her flat was at the top of Garnethill, the highest hill in Glasgow, and the craggy northside lay before her, polka dotted with cloud shadows. In the street below art students were winding their way up to their morning classes.’

Mina talked about it: ‘Yeah that’s it, Maureen O’Donnell lives in that flat behind the trees there. So all the stuff, you know the police are driving up here and she’s watching people out the window, at one point she thinks about killing herself by jumping out the window. At the very start of Garnethill she’s looking out over the M8 there, and it’s one of those Glasgow days where it could go you know it could be a storm or it could be gorgeous.’ The trees are still there, we spot the place easily.

Kelvinside

The very elegant 18 Park Circus is the sinister setting for Alasdair Gray’s Frankenstein-inspired novel ‘Poor Things’: ‘Outside the dining-room life at 18 Park Circus was splendidly commonplace. After the evening meal, we tended the sick animals in …’

‘It was a tall, gloomy terrace house in Park Circus, and in the lobby, he and his Newfoundland dog were noisily welcomed by two Saint Bernards, an Alsatian and an Afghan hound. He led me straight past them, down a stair to the basement and out into a narrow garden between high walls. Near the house was a paved part with a wooden doocot and pigeons, then came vegetable plots and a small lawn surrounded by a low fence.’

Botanic Gardens

Not far from Byres Road, the Botanic Gardens offer a tranquil blend of green space and woodland walks. They are also home to two glasshouses, one of these being the beautiful Kibble Palace, which houses plants from all around the world and marble statues.

Anne MacLeod evokes the place in her poem ‘In The Kibble Palace; Sunday Morning, of which this is an excerpt:

‘The glass rood curves in onion splendour

Green as unpicked fruit; light struggles

To diffuse through panes as thick

With mould as glass, swims greenly over foliage

Preying on deep-sea lack of rays.’

Gerry Loose was Poet in Residence here and edited a collection of botanic poetry, ‘Ten Seasons – Ten Seasons: Explorations’, published in 2007.

He describes the gardens:

He describes the gardens:

‘Here on any given day are children playing, with another generation sitting on benches; courting taking place in the hot house and amongst the shady trees; on those self-same benches are memorial plaques to people now dead but whose absent presence remains strong…people enjoying themselves in an old way that crosses boundaries and cultures in the shared pleasure of mingling to common purpose in a garden.’

One of the poems in the collection is Liz Lochhead’s ‘The Beekeeper’, for Carol Ann Duffy, which begins:

‘Happy as haystacks are my quiet hives

From this distance

And through the bevel of this window’s glass.

This is the place I robe myself

In net and hat and gloves…’

River Kelvin & The Kelvin Walkway

Mandy Haggith was Poet in Residence at the Royal Botanical Gardens Edinburgh in 2013, and she has a keen appreciation of nature. In her collection of poems, ‘Castings’ (2008), one section – ‘Casting Off’ – is all about the River Kelvin as it passes through Glasgow and merits a good read.

The Kelvin Walkway is a beautiful walk, stretching ten miles along the banks of the River Kelvin from Kelvinhaugh all the way out to Milngavie. It’s pretty much in the middle of Glasgow but it’s one of those places where you really don’t feel like you’re in the middle of a big city. You can find a Google map of it here

The Kelvin Walkway is a beautiful walk, stretching ten miles along the banks of the River Kelvin from Kelvinhaugh all the way out to Milngavie. It’s pretty much in the middle of Glasgow but it’s one of those places where you really don’t feel like you’re in the middle of a big city. You can find a Google map of it here

University of Glasgow

One of my favourite buildings on our walk, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the High Gothic revival style. If this is your style, then this is truly a signature building.

One of my favourite buildings on our walk, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the High Gothic revival style. If this is your style, then this is truly a signature building.

Philip Hobsbaum formed the ‘Glasgow Group’ of poets here in the 1960s, whilst he was a lecturer. It was a group in the same style as his London and Belfast gatherings, that brought writers together informally to share their work. It is often regarded as the point of origin for what would become a remarkable literary flourishing. The group included Tom Leonard, Alasdair Gray, James Kelman, Aonghas Macneacail and Jeff Torrington. Alasdair Gray read to the group early drafts of his novel Lanark.

Riverside Museum, Glasgow

The Riverside Museum was designed by internationally renowned architect, Dame Zaha Hadid, her first major building in Britain, dubbed ‘Glasgow’s Guggenheim’ (not sure it quite matches up to that…). Located at the junction of the Rivers Kelvin and Clyde, it houses the city’s transport and technology collections, which have been gathered over the centuries and reflect the important part Glasgow has played in the world through its contributions to heavy industries like shipbuilding, train manufacturing and engineering.

The Riverside Museum was designed by internationally renowned architect, Dame Zaha Hadid, her first major building in Britain, dubbed ‘Glasgow’s Guggenheim’ (not sure it quite matches up to that…). Located at the junction of the Rivers Kelvin and Clyde, it houses the city’s transport and technology collections, which have been gathered over the centuries and reflect the important part Glasgow has played in the world through its contributions to heavy industries like shipbuilding, train manufacturing and engineering.

The Clyde and Clyde Way

As we reach the water of the Clyde, we are reminded of Jackie Kay’s ‘In My Country’ which tackles the issue of accepting one’s own identity in a society where it might feel rejected, or not accepted:

As we reach the water of the Clyde, we are reminded of Jackie Kay’s ‘In My Country’ which tackles the issue of accepting one’s own identity in a society where it might feel rejected, or not accepted:

‘Walking by the waters,

down where an honest river

shakes hands with the sea,

a woman passed round me

in a slow, watchful circle,

as if I were a superstition;

or the worst dregs of her imagination,

so when she finally spoke her words spliced into bars

of an old wheel. A segment of air.

Where do you come from?

‘Here,’ I said, ‘Here. These parts.’

Edwin Morgan describes this stretch of the walk too, in his sixth sonnet, which begins:

‘The North Sea oil-strike tilts east Scotland up,

and the great sick Clyde shivers in its bed.’

Glasgow Green

Glasgow Green is the city’s oldest park and is where we find what is apparently the largest terracotta fountain in the world, the Doulton Fountain, and the beautiful McLennan Arch. Also set within this expansive park is the People’s Palace, a museum dedicated to the social history of Glasgow; and one of the city’s most unusual buildings, Templeton on the Green, which has a detailed design based on the famous Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Glasgow Green is the city’s oldest park and is where we find what is apparently the largest terracotta fountain in the world, the Doulton Fountain, and the beautiful McLennan Arch. Also set within this expansive park is the People’s Palace, a museum dedicated to the social history of Glasgow; and one of the city’s most unusual buildings, Templeton on the Green, which has a detailed design based on the famous Doge’s Palace in Venice.

It is the setting too, for one of the most famous and unsettling poems about Glasgow, Edward Morgan’s ‘Glasgow Green’, of which this is an excerpt:

‘…This is not a delicate nightmare

you carry to the point of fear

and wake from, it is life, the sweat

is real, the wrestling under a bush

is real, the dirty starless river

is the real Clyde, with a dishrag dawn

it rinses the horrors of the night

but cannot make them clean:

though washing blows

where the women watch

by day,

and children run,

on Glasgow Green…’

and concludes:

‘Let the women sit in the Green

and rock their prams as the sheets

blow and whip in the sunlight.

But the beds of married love

are islands in the sea of desire.

Its waves break here, in this park,

splashing the fresh as it trembles

like driftwood through the dark.’

The Necropolis

The Necropolis adjoins Glasgow’s thirteenth-century cathedral (and rather incongruously sits just above the Tennent’s beer factory, with its motto ‘Scotland’s favourite beer. Only ever brewed at Wellpark’). Landscaped from a park in the 1830s as an early example of the Victorian cemetery boom, the Necropolis saw 50,000 burials, many in its 3, 500 formal tombs.

The Necropolis adjoins Glasgow’s thirteenth-century cathedral (and rather incongruously sits just above the Tennent’s beer factory, with its motto ‘Scotland’s favourite beer. Only ever brewed at Wellpark’). Landscaped from a park in the 1830s as an early example of the Victorian cemetery boom, the Necropolis saw 50,000 burials, many in its 3, 500 formal tombs.

Allan Massie, novelist and journalist, describes the amazing view from it: ‘From its height you can see the whole city spread below: the sinuous ribbon of the Clyde, the dismantled shipyards, the few cranes still swinging their mighty loads into place, the tower-blocks, the parks, the Cathedral itself and the spires and towers of countless churches, the terraces which rise to the University on Gilmorehill, and beyond, the hills which enclose Glasgow on three sides and the Firth stretching out into the Atlantic, Glasgow’s old empire. You are aware, on the Necropolis, that Glasgow is a great city on the fringe of the urban world.’ True enough, our sensations exactly as we peer out from the top of the hill.

Alasdair Gray’s novel ‘Lanark’ has numerous mentions of it across all four books. It is the linking territory between the interrelated landscapes of Lanark’s Glasgow and the other world of Unthank.

Lanark frequently draws attention to the seventy-foot-tall John Knox column and statue at the Necropolis’ peak, which we have just reached. Knox’s brooding statuesque presence serves Gray as the perfect emblem of ‘a man of admirable courage and honesty, horrible single-mindedness and cruelty’.

The novel’s closing scenes see Lanark the protagonist perched on the Necropolis, ‘a slightly worried, ordinary old man’ enduring the ‘vibration’, ‘audible throbbing’ and ‘rumbling’ of earthquake and battle, but slightly above it all, just as we feel as we pass through this city of the dead.

George Square

We finish our walk in George Square, the principal civic square of the city, the seat of administration but also numerous political rallies.

We finish our walk in George Square, the principal civic square of the city, the seat of administration but also numerous political rallies.

Perhaps the most famous political event was the Battle of George Square in 1919 when skilled engineers campaigning for a 40-hour working week held a rally. The meeting descended into violence between the protesters and the police, with the Riot Act being read. There were also violent scenes after the Scottish referendum result in 2014 as groups from the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaign clashed.

Jackie Kay’s ‘George Square’ reflects the political aspect of the square:

‘My seventy-seven-year-old father

put his reading glasses on

to help my mother do the buttons

on the back of her dress.

‘What a pair the two of us are!’

my mother said, ‘Me with my sore wrist,

you with your bad eyes, your soft thumbs!’

And off they went, my two parents

to march against the war in Iraq,

him with his plastic hips. Her with her arthritis,

to congregate at George Square, where the banners

waved at each other like old friends, flapping,

where they’d met for so many marches over their years,

for peace on earth, for pity’s sake, for peace, for peace.’

Edwin Morgan’s ‘The Starlings in George Square’ is a humorous observation of this friction between authority and freedom of expression, as represented by the starlings and the young boy.

‘Sundown on the high stonefields!

The darkening roofscape stirs—

thick—alive with starlings

gathered singing in the square—

like a shower of arrows they cross

the flash of a western window,

they bead the wires with jet,

they nestle preening by the lamps

and shine, sidling by the lamps

and sing, shining, they stir

the homeward hurrying crowds…’

A very fitting place for us to conclude our amazing walk.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: The Glasgow Women’s Library, G40 1BP

- Buy books: The Gallery Bookshop, 57 Glassford Street, G1 1UB 11 am -5 pm

- Visit: The Glasgow Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), 350 Sauchiehall St, G2 3JD, home to the Scottish Writers’ Centre

- Browse: Hyndland Bookshop, 143 Hyndland Rd, G12 9JA.

- Visit: The Mitchell Library, North St, G3 7DN; Europe’s largest lending library, with over a million items of stock

- Take: A Guided Tour of the Necropolis, on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, but make sure to book in advance

- Browse: Voltaire and Rousseau Bookshop, 12 Otago Lane, G12 8PB.

- Visit: The Poetry Club, housed in Glasgow’s SWG3, hosts a range of literary events.

- Attend: The Glasgow Book Festival, Aye Write! This Glasgow book festival takes place every year, usually during March and April. Venues across the city play host to fascinating events with well-known authors. Previous festival participants include distinguished writers like Ian Rankin, Liz Lochhead, Val McDermid and Denise Mina.

- Book: Bard in the Botanics

- Read: ‘Laidlaw’ (1977) by William McIlvanney, a ‘tartan noir’ in which Glasgow itself is one of the main characters

- Read: ‘Along Great Western Road’ (2000) by Gordon R. Urquhart, tells the compelling history of Glasgow’s West End, an area that has come to be known as the city’s most artsy and bohemian suburb

Leave a Reply