‘There is no more English spot in all England, and few more beautiful’. Bernard Levin

‘If ever after I’m dead you hear someone whistling this tune on the Malvern Hills, don’t be alarmed, it’s only me.’ Edward Elgar

‘A unique crow’s nest of ancient rock.’ Geoffrey Grigson

The main inspiration for this walk…Piers Plowman (1370s)

My senior professor at Cambridge, Dr Theo Redpath, always seemed other-worldly to me, but incredibly friendly and helpful. He always took other people’s opinions as seriously as his own, even when these issued from opinionated students. His powers of observation and analysis were extraordinary, and nowhere was this more helpful than on the poetic but somewhat inaccessible text of Piers Plowman. Somehow, it didn’t surprise me to hear that in retirement he set up as a wine merchant, he was a man of many parts.

This is the 1976 edition I studied under Theo. Each page was a labour of love for me in terms of annotation and understanding.

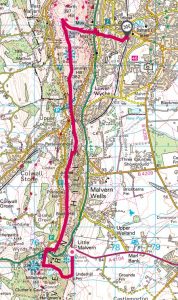

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Steep ascent at start; begin at the British Camp if you wish to avoid this

- Starting point: Little Malvern Priory Church (WR14 4JN)

- Distance: 9.9 km (6.2 miles)

- Walking time: 3 hours 14 minutes

- OS Map: OS Explorer 190. The route can also be found online at https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/7767733/Malvern-Hills

- Facilities: Town facilities in Great Malvern: toilets at British Camp car park

- Best time of year: ideally, an early May morning!

WRITERS FEATURED IN THIS WALK

William Langland (1332-1386), Edward Thomas (1878-1917), Robert Frost (1874-1963), WH Auden (1907-1973), Daniel Defoe (c.1660-1731), Peter Mark Roget (1779-1869), CS Lewis (1898-1963), JRR Tolkien (1897-1973), George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950).

THE MALVERN HILLS

There is something very magical about the Malvern Hills, they poke up out of the ground and can be seen from miles around. They are also more than 600 million years old and dotted with ancient sites including the British Camp, the Shire Ditch and the Wyche Cutting; and many natural springs that offer up the very pure Malvern water that was the key to the town’s growth as a health spa in the nineteenth century.

William Cobbett, the author of Rural Rides, well described the hills as ‘those curious bubblings up’. Celia Fiennes described them as ‘The English Alps’.

Daniel Defoe was amazed that they can be seen ‘so far every way. In particular, we saw them very plainly on the Downs, between Marlborough and Malmsbury; and they say they are seen from the top of Salisbury steeple, which is above 50 miles.’

Alfred Watkins, the proselytiser of ‘ley lines’, believed that Clutters Cave, just south of The British Camp was part of a ley line, a mystical line of magical earth energy.

My grandparents chose to come to Malvern after a life in Hong Kong because the hills reminded them of their former home in The Peak, especially at night as they came across the Severn and saw all the lights of people’s homes and the gas streetlamps glistening on the hills.

My grandparents chose to come to Malvern after a life in Hong Kong because the hills reminded them of their former home in The Peak, especially at night as they came across the Severn and saw all the lights of people’s homes and the gas streetlamps glistening on the hills.

The magic of Malvern has inspired many writers over the centuries, including William Langland (Piers Plowman), Daniel Defoe, George Bernard Shaw, CS Lewis, JRR Tolkien and WH Auden. Today many artists and writers choose to live here.

The composer Edward Elgar should of course get an honourable mention too; he lived much of his life in or near Malvern and was endlessly inspired by the hills. He said of them: ’There is music in the air, music all around us, the world is full of it and you simply take as much of it as you require.’

THE WALK

We arrive at Great Malvern by train, just as CS Lewis did for his regular walking breaks from Oxford. He always took the early, slow train apparently, so he could say his prayers and enjoy the scenery before he arrived.

There doesn’t seem to be any public transport plying the route, so we take a taxi to  Little Malvern Priory Church (about 10 mins), where our adventure begins.

Little Malvern Priory Church (about 10 mins), where our adventure begins.

William Langland

William Langland (1332-1386), the father of English poetry, probably studied with the Benedictine monks at the priory here. His long allegorical poem ‘The Vision of Piers Plowman’ begins in the Malvern Hills with the main character, Will, lying down to rest and having two remarkable dreams. Two of the stained-glass windows in the church feature this story.

William Langland (1332-1386), the father of English poetry, probably studied with the Benedictine monks at the priory here. His long allegorical poem ‘The Vision of Piers Plowman’ begins in the Malvern Hills with the main character, Will, lying down to rest and having two remarkable dreams. Two of the stained-glass windows in the church feature this story.

Langland seemed to find great peace in his studies at the priory:

‘For if heaven be on this earth

and ease to any soul

It is in the cloister and in the learning

by many proofs I find

For in the cloister cometh no man to chide

or to fight

But all is courtesy here

And books to read and to learn’.

Looking around it is not hard to see why; a tranquil fold in the Malvern Hills with a stream cascading down a wooded valley.

We pick a route up to the British Camp from here that would seem the most logical to take, alongside the stream that would have fed the Priory fish ponds – still does in fact. No doubt William Langland would have walked up it many times himself to relax after a long day of ‘learning by many proofs’.

And maybe he paused right here, on the grassy bank of the stream, fed by the Owl’s Hole Spring, and envisaged the lines that began the great canon of English poetry:

‘Ac on a May morwenynge on Malverne hilles

Me bifel a ferly, of Fairye me thoghte.

I was wery forwandred and wente me to reste

Under a brood bank by a bourne syde;

And as I lay and lenede and loked on the watres,

I slombred into a slepyng, it sweyed so murye.’

(But on a May morning on Malvern Hills

A wonder befell me, an enchantment I thought.

I was weary with wandering and went for a rest

Under a broad bank beside a stream

And as I lay and leaned down and looked on the waters

I fell into a sleep as it flowed so sweetly.)

And so Piers Plowman’s dream begins… and the nightmare begins for Term 1 Day 1 Eng. Lit. undergraduates asked to read out aloud or translate passages…how many ever reached the end we will never know.

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost

We, on the other hand, certainly need to finish today’s walk, so we continue climbing up the hill, skirting around the reservoir to reach the British Camp, the exact same route that Edward Thomas and Robert Frost had taken back in 1914 on one of their many walking excursions.

Edward Thomas (1878-1917) was a literary reviewer and Robert Frost (1874-1963) was an unknown poet when they had become good friends the year before. Thomas was one of the first to see Frost’s greatness as a poet, and Frost persuaded Thomas to switch from prose to poetry – so they both played a key part in each other’s literary development.

Their friendship blossomed in 1914 when they both rented properties in nearby Leddington, and they often took long walks together. Frost called these their ‘talks-walking’ and in them, their conversations and creativity roamed freely. Thomas’ poem ‘The Sun Used To Shine’ captures these beautiful ‘in the moment’ experiences:

‘The sun used to shine while we two walked

Slowly together, paused and started

Again, and sometimes mused, sometimes talked

As either pleased, and cheerfully parted

Each night. We never disagreed

Which gate to rest on. The to be

And the late past we gave small heed…’

The route that we share a small part of with them today took them from their homes in Leddington, through Bromesberrow, Hollybush, Castlemorton Common, up to the summit of the Camp, then back along the Ridgeway via Eastnor Park to Leddington again – around twenty miles at least in one day. It looks like rather an erratic route (`in a long loop` as Thomas preferred to describe it), but Thomas was famous for vacillating between routes, and Frost used to gently chide him, saying at one point ‘No matter which road you take, you’ll always sigh, and wish you’d taken another’.

This dynamic formed the idea for one of the most famous poems of the twentieth century, ‘The Road Not Taken’, which opens:

‘Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;’

Unfortunately, it also represented a parting of the ways between Thomas and Frost. Thomas wrongly interpreted it as a veiled message to him to make up his mind and go to war, which in the end he did and was killed in action in 1917.

We have no such problems with our route-finding, courtesy of the ‘lumpy’ spine of the Malverns guiding us ever northwards.

The British Camp

The British Camp

The British Camp is an Iron Age Hill Fort with a Norman castle superimposed on it. Folklore says that the ancient British chieftain Caractacus made his last stand against the Romans here.

The British Camp has inspired many, including Turner who drew it, and Elgar who composed a cantata called ‘Caractacus’ about it. In the sixteenth century, John Evelyn described it as ‘one of the goodliest vistas in England’.

WH Auden (1907-1973)

WH Auden was a great admirer of both Edward Thomas and Robert Frost. ‘I have learned a lot from Frost,’ he said, ‘I have always admired his work enormously’.

Looking down off the side of the hills to our left (west) we can just spot the playing fields of a school at Colwall. This is the Downs School, where Auden taught in the 1930s. If he’d walked straight up the hill from there to here, then ‘here’ is where this poem in ‘Look, Stranger’ must be set:

‘Here on the cropped grass of the narrow ridge I stand

A fathom of earth, alive in air,

aloof as an admiral on the old rocks,

England below me:

eastward across the Midland plains

An express is leaving for a sailor’s country;

Westward is Wales

Where on clear evenings the retired and rich

From the French windows of their sheltered mansions

See the Sugarloaf standing, an upright sentinel

Over Abergavenny.’

(from Poem XVII, Look, Stranger! 1936)

He was a popular if somewhat eccentric teacher, famously taking his bed out onto the lawn one summer and writing the poem that opened ‘Out on the lawn I lie in bed’. It was a happy and productive period for him:

‘Lucky this point in time and space

is chosen as my working place.’

We dip down and then up out of the Wyche Cutting and begin the climb to the Worcestershire Beacon.

Daniel Defoe (c.1660-1731)

About 350 metres north of the cutting we come to a circular flat stone that marks the site of an old Gold Mine, first recorded in 1633. Daniel Defoe had poked round a bit on one of his journeys across the country in the 1720s: ‘They talk much of mines of gold and silver, which are certainly to be found here, if they were but look’d for, and that Mauvern wou’d out do Potosi for wealth; but ’tis probable if there is such wealth, it lies too deep for this idle generation to find out, and perhaps to search for.’

The record remains hazy as to whether any gold was ever discovered or indeed any gold was ever there in the first place! A Colorado gold rush it was not…

Peter Mark Roget (1779-1869)

Roget died, passed away, breathed his last departed this life, became no more, deceased in West Malvern, which is coming into sight now down on our left. He, of course, was the creator of Roget’s Thesaurus, first published in 1852, its aim, he wrote in the preface, was ‘to hold out a helping hand to those who want to possess and/or master the art of communicating their thoughts by means of either written or spoken language.’

Many writers have declared their debt to Roget, including Peter Pan’s creator, J.M. Barrie, who put a copy of the Thesaurus in Captain Hook’s cabin so he could declare: ‘The man is not wholly evil — he has a Thesaurus in his cabin.’ And Sylvia Plath, who called herself ‘Roget’s Strumpet’ to acknowledge all the word choices he gave her.

Roget died at the age of 90 whilst on holiday in the Malverns and is buried in the cemetery of St James’s Church in West Malvern. If you want to raise a pint to him, there is a beer named after him: Roget by Malvern Hills Brewery, an English Mild Ale.

Mary and William Wordsworth spent a month’s holiday at the Old Vicarage just to the south of the churchyard in June 1849. Their nephew was the vicar of West Malvern. Despite Wordsworth’s advanced age – he was 79 when he stayed there, he walked extensively, even as far as Hanley Swan which is over the hill at least six miles away.

CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien

CS Lewis had attended school in Malvern from the age of 13, first prep school, then Malvern College. Although he had mixed feelings about his experiences there, he always loved the landscape and came back many times with his Oxford friend JRR Tolkien to hill-walk.

Their host was George Sayer, English master at Clifton College, Lewis’ former pupil at Magdalen College and a close friend for three decades. They often walked much of the same ridge we are walking today.

Sayer recounts; ‘Jack (C.S. Lewis) rarely tinkered with the details of these trips, since the goal was always the same – to walk and talk with friends. He wore a rumpled tweed jacket with the obligatory leather elbow patches, baggy wool pants, walking shoes and an old hat. He had a battered rucksack and he never carried a watch.

‘Beauty was so important to Jack and so was good conversation. What could be better than putting the two together? One could not have found a better walking companion.’

Sayer also recalls Tolkien’s preoccupations: ‘He lived the book (‘The Lord of the Rings’) as we walked, sometimes comparing parts of the hills with, for instance, the White Mountains that marked the border between Rohan and Gondor’.

One of their favourite watering holes was the Unicorn pub in Great Malvern (which we pass later). The plaque on the front of the pub reads: ‘At this inn C. S. LEWIS – Scholar and author of THE NARNIA CHRONICLES met frequently with literary and hill-walking friends’.

The story goes that, after drinking here one winter evening, they were walking home when it started to snow. They saw a lamp post shining out through the snow, and Lewis turned to his friends and said, ‘That would make a very nice opening line to a book’. Which of course it did – it inspired the gas lamp in the Narnian Wood at the start of ‘The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe’.

St Ann’s Well

The quality of Malvern spring water was well known as far back as the fifteenth century as a curative for the ‘many maladies suffered by mediaeval folk’.

It became famous in the eighteenth century thanks to its promotion by Dr John Wall, a Worcestershire physician, who analysed the water and found that ‘the efficacy of this water seems chiefly to arise from its great purity’. The Malvern marketers got to work and came up with the pithy couplet:

‘The Malvern water, says Dr Wall

Is famed for containing just nothing at all.’

Thus did St Ann’s Well become one of the most popular watering places for wealthy invalids in the early days of the Water Cure (hydrotherapy). Charles Dickens brought his wife here in 1851 and declared ‘Mrs Dickens has derived great advantage, I am glad to say, from this place’.

The way we are going down now used to be negotiated by donkeys, who carried visitors up the hill, including the young Princess Victoria when she rode up in 1831 and officially opened a new path from St Ann’s Delight to Foley Walk.

George Bernard Shaw

Priory Park provides a tranquil centre to Great Malvern and is bordered by the Malvern Theatres.

George Bernard Shaw was the patron of the Malvern Annual Summer Festival, which ran here from 1929-1939, and several of his plays had their premieres here. He became a very well-known figure around town (and, according to my mother, who was a child at the time, a very haughty one).

We make it back to the station from whence our journey had begun.

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: Madresfield Court, madresfieldestate.co.uk, where Evelyn Waugh was a regular visitor. Especially impressive is the Arts & Crafts chapel.

- Visit: Little Malvern Court & Gardens, littlemalverncourt.co.uk the site of the Little Malvern Priory

- Take: The Elgar Route around Malvern, which you can download at visitthemalverns.org/things-to-do

- Read: ‘A Conscious Englishman’ (2013), by Margaret Keeping, the story of the last years of Edward Thomas’ life.

Leave a Reply