‘A naturally evolved local organism, like a giant protozoa’

‘These early years anchored both of us up there for life’

The inspiration for this walk…Ted Hughes’ poetry

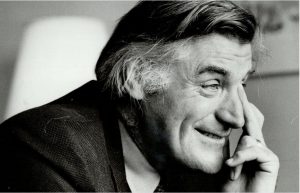

Ted Hughes’ poetry was brought vividly to life for me by my first English Literature teacher, Philip Balkwill, when I was twelve . He was one of those teachers his pupils never forget, it was as if a light bulb had gone on and the modern world had suddenly begun.

Even though Philip was only in his early thirties then, he already had a mop of grey hair and would come bounding into our lessons almost always inexplicably late. He would throw a hastily photostated foolscap copy of the poem of the day onto each of our desks, with its exquisitely intoxicating smell (methanol?) which we immediately raised to our noses in pleasure (was that really what made me so keen on poetry?!), and asked one of us to read it aloud. What followed was thirty minutes of electric magic as we got to the heart of the poem and its meaning, but never losing sight of the cadence and emotional effect.

The poem I always remember most vividly is ‘Thought-Fox’ and its ending lines…‘Till, with a sudden hot sharp stink of fox/ It enters the dark hole of the head.’

This edition (pictured) was the one I had at school.

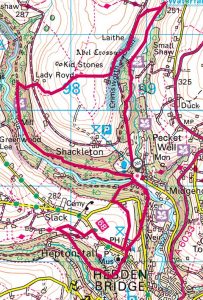

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Quite a lot of steep inclines and descents. If you run out of time, head for Slack along the road rather than down Colden Clough

- Starting point: New Bridge Car Park, Midgehole, HX7 7AL

- Distance: Stage I: 4.7 km (3 miles); Stage II: 7.4 km (4.7 miles)

- Walking time: Stage I: 1hr 43 mins; Stage II: 2hrs 32 mins

- OS Map: OL 21. The map can also be found online at: https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/9916231/Heptonstall-West-Yorkshire-Ted-Hughes

- Facilities: Heptonstall, Gibson Mill

TED HUGHES (1930-1998)

Ted Hughes grew up in the Upper Calder Valley and his poetry is firmly based in its moors and valleys. As a young boy, he loved hunting and fishing with his elder brother Gerald and his early poetry, such as The Hawk in the Rain (1957), contains powerful imagery of the natural world.

Ted Hughes grew up in the Upper Calder Valley and his poetry is firmly based in its moors and valleys. As a young boy, he loved hunting and fishing with his elder brother Gerald and his early poetry, such as The Hawk in the Rain (1957), contains powerful imagery of the natural world.

Ted Hughes’ sharp perception of nature and its revelatory power was honed on these hunting trips with his brother. They rose before dawn to watch and wait, almost in a trancelike state of concentration, and when an animal appeared it would always be sudden and unexpected, making his hair stand on end. It was a kind of revelation, a moment of animism (think ‘Thought-Fox’).

Simon Armitage observes that ‘the anthropology, religion, natural history, and geography of the area’ provided Ted Hughes with ‘a model for nearly all of his future work’. Hughes himself referred to the Calder Valley as his ‘tuning fork’. His poetic style is perhaps best described as post-pastoral, rooted in the relationship between man and nature, both their creative and destructive elements. His poetry does not celebrate a pastoral idyll but rather seeks a deeper truth through the allegory of nature.

In Hughes’ world, people, stone, and what he called ‘the mothers’, the sustaining elements of earth, air, fire, and water, were all conscripted by the industrialists as economic resources. In the early 1800s, the Calder Valley became the cradle for the Industrial Revolution in textiles, and the Calder became ‘the hardest-worked river in England’.

Ted Hughes thought of the land as a huge creature, harnessed by dry stone walls (‘harness on the long moors’), but as the Industrial Revolution played out gently shaking herself free of walls, chimneys, chapels, mills, and houses. In a letter, he describes what fascinated him about the place: ‘The collision of the pathos of the early industrial revolution – that valley was the cradle of it – with the wildness of the place.’ ‘Remains of Elmet’ (1979), a collaboration with the photographer Fay Godwin, was a brilliant portrait of this shifting world. The book contains photos paired with vivid poems that seem to spring from a strangely imagined world of vast creatures, stone gods and huge dramas played out on a geological timescale.

Hughes said that the move to South Yorkshire when he was eight ‘really sealed off my first seven years so that now my first seven years seems almost half my life. I’ve remembered almost everything because it was sealed off in that particular way and became a sort of brain – another subsidiary brain for me’. Or as his brother Gerald said: ‘These early years anchored both of us up there for life.’

THE WALK

We start our walk from the car park in New Bridge (National Trust, charges apply) and walk south to  Heptonstall.

Heptonstall.

Heptonstall

Heptonstall is perched on an exposed hill above Hebden.

It has an extraordinary feel about it, especially arriving from the north on foot. We visit the church where both Ted’s parents and his wife Sylvia Plath are buried.

It has an extraordinary feel about it, especially arriving from the north on foot. We visit the church where both Ted’s parents and his wife Sylvia Plath are buried.  For him, this church was also a symbolic focal point of the Upper Calder Valley.

For him, this church was also a symbolic focal point of the Upper Calder Valley.

Heptonstall Old Church

A great bird landed here.

Its song drew men out of rock,

Living men out of bog and heather.Its song put a light in the valleys

And harness on the long moors.Its song brought a crystal from space

And set it in men’s heads.Then the bird died.

Its giant bones

Blackened and became a mystery.The crystal in men’s heads

Blackened and fell to pieces.The valleys went out.

The moorland broke loose.’

Silvia Plath’s grave is in the newer cemetery beyond Back Lane on the south side of the church. The day we went there was an elderly gentleman reclining on a bench and, after reassuring myself that he was not in deep mourning, I ventured to ask him to point me to Silvia’s grave. A smile crossed his face, and he explained that he came to the graveyard regularly to check that the grave was well-kept. Apparently, Frieda, Silvia’s daughter, was very grateful for what he did and regularly visited from her home in Wales too. This picture of him is in front of the nearby grave of Asa Beneviste (1925-1990), an American-born poet, typographer and publisher. He co-founded and managed the pioneering Trigram Press.

Silvia Plath’s grave is in the newer cemetery beyond Back Lane on the south side of the church. The day we went there was an elderly gentleman reclining on a bench and, after reassuring myself that he was not in deep mourning, I ventured to ask him to point me to Silvia’s grave. A smile crossed his face, and he explained that he came to the graveyard regularly to check that the grave was well-kept. Apparently, Frieda, Silvia’s daughter, was very grateful for what he did and regularly visited from her home in Wales too. This picture of him is in front of the nearby grave of Asa Beneviste (1925-1990), an American-born poet, typographer and publisher. He co-founded and managed the pioneering Trigram Press.

In the 1980s Benveniste moved to Heptonstall where they operated a secondhand bookshop. When he died in 1990, he was buried in the graveyard, with a gravestone that reads: ‘Foolish Enough to Have Been a Poet’. He was both pleased and amused that his grave was to be within speaking distance of Sylvia Plath’s own gravestone a few feet away.

Colden Clough

A footpath runs down from the church into the steep wooded valley of Colden Clough, where tall mill chimneys poke through the trees by the banks of Colden Water. Astonishingly, thirteen mills were powered by this small river back in the nineteenth century.

Remnants of these mills and factory workings combine with woodland and a large mixture of wildlife to create a very special place. Ted Hughes’ poem ‘Chinese History of Colden Water’ describes it beautifully:

‘A fallen immortal found this valley –

Leafy conch of whispers

On the shore of heaven.’

In 1969 Ted Hughes bought an eighteenth-century millowner’s house called Lumb Bank on the edge of this valley, with the intention of living there. But he soon tired of it as a place to live, and it became the Arvon Foundation, a base for creative writing courses. Ted Hughes gave regular readings there from the mid-1970s onwards. It is still going strong.

In 1969 Ted Hughes bought an eighteenth-century millowner’s house called Lumb Bank on the edge of this valley, with the intention of living there. But he soon tired of it as a place to live, and it became the Arvon Foundation, a base for creative writing courses. Ted Hughes gave regular readings there from the mid-1970s onwards. It is still going strong.

Slack

In 1952, whilst Ted was studying at the University of Cambridge, Hughes’ parents moved back to the Calder Valley, to The Beacon, a modest house on the southeastern side of Slack, with panoramic views and consequently often very windy! Hughes returned intermittently throughout the 1950s, bringing his wife Sylvia Plath to visit after their marriage in 1956. He wrote ‘Six Young Men’ here that year.

Ted and Sylvia stayed there for a few months in 1957 until their departure to America. Ted wrote of the ‘happy life Sylvia and I lead’, and of how, when they became ‘fed up’ of writing and critiquing each other’s work, they would ‘walk out into the country and sit for hours watching things’.

‘Wind’ (1957) was inspired by this house. ![]() We see its exposed position facing west and the old coal house on the east side is still there, protected from the prevailing wind.

We see its exposed position facing west and the old coal house on the east side is still there, protected from the prevailing wind.

‘This house has been far out at sea all night,

The woods crashing through darkness, the booming hills,

Winds stampeding the fields under the window

Floundering black astride and blinding wet

Till day rose; then under an orange sky

The hills had new places, and wind wielded

Blade-light, luminous black and emerald,

Flexing like the lens of a mad eye.

At noon I scaled along the house-side as far as

The coal-house door’

One of his more comic poems, ‘Football at Slack’, is also set in this tiny village:

Between plunging valleys, on a bareback of hill

Men in bunting colours

Bounced, and their blown ball bounced.

And the valleys blued unthinkable

Under depth of Atlantic depression —

But the wingers leapt, they bicycled in air

And the goalie flew horizontal’

Crown Point

![]() Ted grew up in a household overshadowed by the experiences of the First World War. His father was one of only seventeen survivors of a battalion of a thousand men massacred at Gallipoli. It became a preoccupation for him in his writing:

Ted grew up in a household overshadowed by the experiences of the First World War. His father was one of only seventeen survivors of a battalion of a thousand men massacred at Gallipoli. It became a preoccupation for him in his writing:

‘The big, ever-present, overshadowing thing was the First World War, in which my father and my Uncles fought…where a single bad ten minutes in no man’s land would wipe out a street or even a village.’

The ‘survivors’ are commemorated in the poem ‘Crown Point Pensioners’. The two benches on which they sit, on a mound of earth at Crown Point, are still here a few yards east along the road to Heptonstall, with the same stunning views across to Stoodley Pike:

‘Old faces, old roots.

Indigenous memories.

Flat caps, polished knobs

On favoured sticks.

Under the blue, widening morning and the high lark.

The map of their lives, like the chart of an old game,

Lies open below them.

… Singers of a lost kingdom.

Wild melody, wilful improvisations.

Stirred to hear still the authentic tones

The reverberations their fathers

Drew from these hill-liftings and hill-hollows.’

We complete our first circuit and then head up Hardcastle Crags, a delightful stroll up Hebden Dale.

Gibson Mill

Gibson Mill, built around 1800, is situated in woodland beside Hebden Water. It was driven by a water wheel and produced cotton cloth up until 1890 when it closed.

Gibson Mill, built around 1800, is situated in woodland beside Hebden Water. It was driven by a water wheel and produced cotton cloth up until 1890 when it closed.

Ted Hughes would no doubt be amused that today Gibson Mill has become a model for green living. It draws on the site’s natural resources including sunlight, spring water and wood, as well as its 1926 turbine and a log-burning stove, for hot water, electricity and heating.

We stopped for a quick coffee, this is my walking companion Mark Sutcliffe, nowadays a Lancastrian, but we found the names of many of his forbears in the churchyard at Heptonstall.

We stopped for a quick coffee, this is my walking companion Mark Sutcliffe, nowadays a Lancastrian, but we found the names of many of his forbears in the churchyard at Heptonstall.

Hardcastle Crags

Ted Hughes’ mother Edith had a great love of the countryside and introduced all her children to it through long walks. The crags were one of her favourite spots:

‘Think often of the silent valley, for the god lives there.’

In Hardcastle Crags, that echoey museum,

Where she dug the leaf mould for her handful of garden

And taught you to walk, others are making poems.

…Leaf mould. Blood-warm. Fibres crumbled alive

Between thumb and finger.

Feel again

The clogs twanging your footsoles, on the street’s steepness,

As you escaped.’

Across the moor

Our route then cuts across the moor over Turn Hill. Feeling very small in the landscape, we are reminded of Ted Hughes’ lines:

‘Moors …

Are a stage for the performance of heaven.

Any audience is incidental.’

Lumb Bridge

At Lumb Bridge, we soon find the plaque commemorating the poem ‘Six Young Men’, which was inspired by an old photograph taken at this spot of six young men who were all soon to lose their lives in the war.

At Lumb Bridge, we soon find the plaque commemorating the poem ‘Six Young Men’, which was inspired by an old photograph taken at this spot of six young men who were all soon to lose their lives in the war.

‘All are trimmed for a Sunday jaunt. I know

That bilberried bank, that thick tree, that black wall,

Which are there yet and not changed. From where these sit

You hear the water of seven streams fall

To the roarer at the bottom, and through all

The leafy valley a rumouring of air go.

Pictured here, their expressions listen yet,

And still that valley has not changed its sound

Though their faces are four decades under the ground.’

A moment of pure linkage between poem and place, it takes our breath away.

Abel Cross

Abel Cross, ‘where the Mothers/Gallop their souls/Where the howlings of the heaven/Pour down onto earth,’ comprises two marker stones locally nicknamed ‘Mourning & Vanity’. Dating back to mediaeval times, these wayside crosses served both to reinforce the Christian faith in travellers, but also as way-markers or boundary markers.

Abel Cross, ‘where the Mothers/Gallop their souls/Where the howlings of the heaven/Pour down onto earth,’ comprises two marker stones locally nicknamed ‘Mourning & Vanity’. Dating back to mediaeval times, these wayside crosses served both to reinforce the Christian faith in travellers, but also as way-markers or boundary markers.

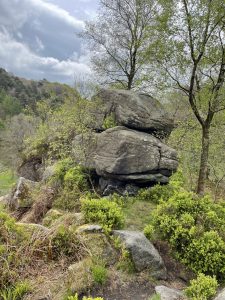

The quarry (or ‘delf’)

At the southwest end of Hirst Fields is an old quarry.

At the southwest end of Hirst Fields is an old quarry.

This is the very spot where Ted camped for three days with his brother Gerald: ‘It was in Crimsworth Dean, camping on that level first. Beside what’s now a council stone dump under a little cliff beside the lane going up, in around 1937 or earlier, that I had the dream that turned later into all my writing. A sacred space for me.’

The short story ‘Deadfall’ recounts this dream, in which Ted awakens in the tent at night to be led to a fox caught in a deadfall trap by its spirit in the form of an old woman. In the morning Gerald and Ted found a fox in a real trap nearby. The deadfall can still be seen at the foot of a pine tree near the top of the wood. The story begins:

The short story ‘Deadfall’ recounts this dream, in which Ted awakens in the tent at night to be led to a fox caught in a deadfall trap by its spirit in the form of an old woman. In the morning Gerald and Ted found a fox in a real trap nearby. The deadfall can still be seen at the foot of a pine tree near the top of the wood. The story begins:

‘Camping is mainly about camp-fires, food cooked on camp-fires, and going to sleep in a tent. And getting up in the wet dawn. We planned to get up at dawn, maybe before dawn, when the rabbits would be dopey, bobbing about in the long dewy grass. Our precious, beautiful thing, my brother’s gleaming American rifle, lay in the tent, on a blanket.’

Shackleton

‘The Horses’ is a recollection of one of those ‘before dawn’ experiences, getting up and scrambling up out of the trees and into the field beyond Shackleton:

‘I climbed through woods in the hour-before-dawn dark.

Evil air, a frost-making stillness,

Not a leaf, not a bird –

A world cast in frost. I came out above the wood

Where my breath left tortuous statues in the iron light.

But the valleys were draining the darkness

Till the moorline – blackening dregs of the brightening grey –

Halved the sky ahead. And I saw the horses:

Huge in the dense grey – ten together –

Megalith-still. They breathed, making no move,

with draped manes and tilted hind-hooves,

Making no sound.

I passed: not one snorted or jerked its head.

Grey silent fragments

Of a grey silent world.

I listened in emptiness on the moor-ridge.

The curlew’s tear turned its edge on the silence.’

We return to our starting point and are suddenly jolted back into the contemporary world. Or not quite.  We finish with a pint at the Stubbing Wharf, between the river and the canal, where Ted Hughes had sat with Sylvia in 1959 when she was pregnant with their first child, pondering where they might live. This is how his poem ‘Stubbing Wharfe’ begins;

We finish with a pint at the Stubbing Wharf, between the river and the canal, where Ted Hughes had sat with Sylvia in 1959 when she was pregnant with their first child, pondering where they might live. This is how his poem ‘Stubbing Wharfe’ begins;

‘Between the canal and the river

We sat in the gummy dark bar.’

In just a few hours we too feel anchored to this extraordinary place!

OTHER STUFF

- Visit: The Ted Hughes Arvon Centre, Lumb Bank, where Ted Hughes’ writing desk is. See www.arvon.org/centres/lumb-bank/. Also, sometimes for rent via Airbnb.

- Attend: the Ted Hughes Festival, held each year in Mytholmroyd, led by the Elmet Trust, an educational body founded to support his work and legacy. www.theelmettrust.org

- Watch: ‘Stronger Than Death’ (BBC2, 2015) which examines Hughes’s life and work.

- Stay at: Hughes’s birthplace home in Mytholmroyd, 1 Aspinall St, which is available as a holiday let and writer’s retreat. www.theelmettrust.org/ted-hughes-house-elmet-trust

- Follow: The Ted Hughes paper trail, a two-mile walk-in Mexborough highlighting locations important to Hughes and other points on the route of historic interest. www.tedhughesproject.com/the-trail/

- Watch: ‘Ted and Sylvia’ (2003), which explored Plath’s relationship with Ted Hughes

- Read: ‘Ted Hughes, from Cambridge to Collected’, by M Wormald, 2013, which includes Simon Armitage’s ‘The Ascent of Ted Hughes; Conquering the Calder Valley’.

- Browse: The Book Case, 29 Market St, Hebden Bridge, HX7 6EU, www.bookcase.co.uk, 01422 84535

- Buy: Map 2: Crimsworth Dean, from a series of maps called Discovering Ted Hughes’s Yorkshire, by Christopher Goddard (www.chistophergoddard.net )

- Try and find: a booklet called The Ted Hughes Trail in Crimsworth Dean, published by the Elmet Trust and based on Donald Crossley’s research.

Leave a Reply