‘Where else could a writer hope to meet the whole world within a one-mile radius?’

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Pavements, hills

- Starting point: Queen’s Park, NW6. The nearest tube is Queen’s Park

- Distance: 8.5 km (5.5 miles)

- Walking time: 2 hrs 30 mins

- OS Map: can be found online at https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/9936654/Kilburn-London-Zadie-Smith

- Facilities: Pubs, cafés

ZADIE SMITH (1975-

Zadie Smith was born and brought up in Kilburn and later returned to live there with her family.

Zadie Smith was born and brought up in Kilburn and later returned to live there with her family.

‘I was born in The Ends, and bred there: in fact, I spent the first thirty years of my life in a one-mile radius. Born in a bedsit by Brondesbury Park Station, then moved to Athelstan Gardens Estate further down that same lane, then down to a maisonette just by Willesden Green library, where my mum still lives. When I published White Teeth, I moved to a flat in Chatsworth Road, just by Kilburn Station; when I married, I moved into a house opposite the old flats. I never learnt to drive – still haven’t – so I have walked those streets over and over, passing earlier versions of myself and my memories, at bus-stops, in the parks, in the pubs, corner shops and libraries.’

She attended Malorees Primary in nearby Christchurch Avenue, then ‘Hampstead Comp, which was actually in Cricklewood’. Of that school, she says:

‘I remember an incredible, mixed school where 100 languages were spoken, The late 90s were full of civil wars and a new collection of migrant kids would come to our school. It was incredibly lively and interesting. I was very curious about what was going on in all these flats, going to a friend’s house was like entering a different universe, different faith, different food, different ideas. Constant stimulation’.

Most of her novels take place in this ‘one-mile radius’, notably her first, White Teeth (2000), and NW (2012).

Kilburn is very much a creative fount for Smith, in the same way that Egdon Heath was for Thomas Hardy. Local ‘dialect’ is also very important for both of them, creating a strong sense of place and also differentiating characters, often between those who are always there and those who come back.

But where Smith’s writing differs so much from Thomas Hardy’s is in the variety of her characters. Whereas Thomas Hardy has to rely on psychological needs and fault lines to create diversity amongst essentially a homogenous group of characters from the same spot for generations, Smith’s characters are much more heterogeneous:

‘It is the location of my imagination, and my heart, and I feel very fortunate, as a writer, to have known first-hand the extraordinary borough Brent, officially the most diverse area in London. Where else could a writer hope to meet the whole world within a one-mile radius?’

‘There is simply a multiplicity of voices at work, many of which are absent from the singular, neatly ordered myths of the pretty English village.’

Zadie Smith is a novelist of place

‘I never set out to become a writer connected to a geographic area,’ Smith told an interviewer, “But when you write you have to write out of love.’

As well as the people of the area, she is fascinated by its history: ‘In the 1880s or thereabouts the whole thing went up at once – houses, churches, schools, cemeteries – an optimistic vision of Metroland. Little terraces, faux-Tudor piles. All the mod cons! Indoor toilet, hot water. Well-appointed country living for those tired of the city.’ NW

‘This was famously beautiful countryside with fields and sheep. I felt it subconsciously. Other people saw urban streets but to me it was all beautiful. The walk down the hill from Hampstead to Kilburn, the sunsets and trees. This neighbourhood has been through such incredible change from countryside to city, to immigration and gentrification. It’s the story of a country told in miniature.’

The juxtaposition of Leah and Natalie in ‘NW’

The two protagonists in ‘NW’ – Leah and Natalie (Sheryl) represent the two forces of ‘home’. One (Leah) wants to stay rooted at home, not going beyond the confines of NW, not wanting anything to change in her life. The other (Natalie) always wants to travel away from home, moving out, moving up, moving on.

The two protagonists in ‘NW’ – Leah and Natalie (Sheryl) represent the two forces of ‘home’. One (Leah) wants to stay rooted at home, not going beyond the confines of NW, not wanting anything to change in her life. The other (Natalie) always wants to travel away from home, moving out, moving up, moving on.

When readers first meet Leah, she is ‘in a hammock, in the garden of a basement flat. Fenced in, on all sides’. Leah lets a stranger, Shar, into her home because ‘Leah is as faithful in her allegiance to this two-mile square of the city as other people are to their families, or their countries.’

She thinks to herself, ‘In my mind I am eighteen and if I do nothing if I stand still nothing will change, I will be eighteen always. For always. Time will stop. I’ll never die. Very banal, this fear’.

Natalie’s experience of space is diametrically opposite to Leah’s, Like Leah, she spends time away at university and returns to London soon after. However, unlike Leah, Natalie lives in many different areas of the city before eventually returning home to NW. ‘Natalie continued along her path’.

THE WALK

Towards the end of ‘NW’, Natalie walks out of her home near Queen’s Park – walks out on her husband, her old life – and makes her way across north London to ‘re-discover’ herself. Walking, stripping out the construct of her life, is the therapy:

‘Walking was what she did now, walking was what she was. She was nothing more nor less than the phenomenon of walking. She had no name, no biography, no characteristics.’

It is this very walk that we are retracing today. The chapter titles give us the overview of the route: ‘Willesden Lane to Kilburn High Road’, ‘Shoot Up Hill to Fortune Green’, ‘Hampstead to Archway’, ‘Hampstead Heath’, ‘Corner of Hornsey Lane’, ‘Hornsey Lane’.

‘Willesden Lane to Kilburn High Road’

‘Walked quickly away from Queen’s Park. She passed into where Willesden meets Kilburn. Went by Leah’s Place, then Caldwell.’

‘Without looking where she was going, she began climbing the hill that begins in Willesden and ends in Highgate.’

‘She was making a queer keening noise, like a fox.

As she crossed the road a 98 bus swung by her steeply.’ (the 98 bus runs along Kilburn High Rd)

Queen’s Park is Victorian, leafy and beautifully kept, just where you would expect the successful Natalie (she is a lawyer, her husband a City trader) would live.

Queen’s Park is Victorian, leafy and beautifully kept, just where you would expect the successful Natalie (she is a lawyer, her husband a City trader) would live.

We walk along Winchester Avenue and turn right down Willesden Lane; on our right is Athelstan Gardens Estate,  where Zadie Smith lived as a child. It has much in common with the Caldwell estate of the book, including the stout boundary wall. Caldwell has ‘five blocks connected by walkways and bridges and staircases.’

where Zadie Smith lived as a child. It has much in common with the Caldwell estate of the book, including the stout boundary wall. Caldwell has ‘five blocks connected by walkways and bridges and staircases.’

Natalie bumps into an old school friend, Nathan Bogle, who may be wanting to escape the law, and they walk together and reminisce about the past until ‘they’d reached the end of nostalgia’. Nathan had had a trial for Queen’s Park Rangers football club, originally named after Queen’s Park, but he had not been successful, he says because of bad tendons. Nathan represents the opposite of Natalie, someone who hasn’t made it and has no home – but in this walk, they are briefly united.

‘They crossed the street, past the basketball court’ – this is still there on the intersection of Kimberley Rd and Willesden Lane.

Then they pass by Paddington Old Cemetery, where Nathan ‘leant into the high iron gates, looking in.’ When we pass, these gates are open, and we wander in:

Then they pass by Paddington Old Cemetery, where Nathan ‘leant into the high iron gates, looking in.’ When we pass, these gates are open, and we wander in:

‘When Naomi was small Natalie had strapped her daughter to her chest and walked figure of eights in this cemetery, hoping the child would take her afternoon nap. Local people claimed Arthur Orton was buried in here somewhere. In all her figures of eights she never found him’. But she would have found the grave of Michael Bond (1926-2017), creator of the Paddington Bear books. Incidentally, Arthur Orton was a character who pretended he was someone other than himself to try to inherit the great Tichborne estate – and that is why Natalie was fascinated by him (he is buried there). Her 2023 novel, “The Fraud,” is based on him, recreating the London of the 1860s and the celebrated trial he was involved in.

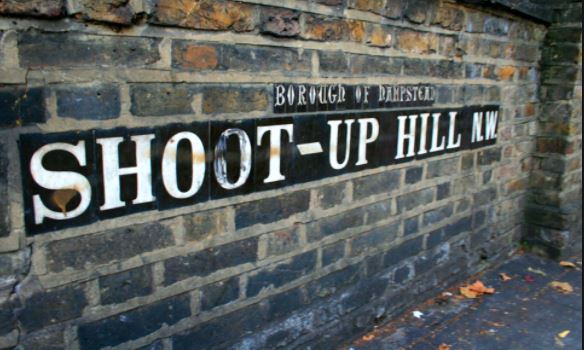

‘Shoot Up Hill to Fortune Green’

‘Where Shoot Up Hill meets Kilburn High Road they stopped, in the forecourt of the tube station’. (Kilburn). This is on the Jubilee Line and is what persuaded Frank, Natalie’s husband, to re-locate to her old neck of the woods, as it goes directly to Canary Wharf (27 minutes) where he works in finance.

They head up Shoot Up Hill, originally named after highwaymen, but now with more sinister drug use connotations. The area changes. ‘The world of council flats lay far behind them, at the bottom of the hill. Victorian houses began to appear …’.

They head up Shoot Up Hill, originally named after highwaymen, but now with more sinister drug use connotations. The area changes. ‘The world of council flats lay far behind them, at the bottom of the hill. Victorian houses began to appear …’.

Not too far up the hill, however, it crests. To continue going up (which is Natalie’s ‘plan’) we turn along Mill Lane, Hillfield Road and Fortune Green Road, which passes Hampstead Cemetery, the comprehensive school that Zadie Smith attended lying behind it. She must have come up this way many times. Zadie Smith modelled the school in White Teeth on this school: ‘Like any school, Glenard Oak had a complex geography.’

We continue to sharply ascend, to Platt’s Lane and an outlying section of Hampstead Heath.

‘Hampstead to Archway’

We are starting to move from urban to rural: ‘Natalie felt the cars very close on her right and on her left brambles and bushes.’

‘That bit of the Heath where the main road runs right through and the pavement disappears.’

‘They stopped in a pub’s doorway, Jack Straw’s Castle.’

Natalie likes the Heath ‘because it’s free, because it’s beautiful. Trees, fresh air, ponds, grass.’

(Hampstead Heath is important in another of Zadie Smith’s novels, Swing Time. The unnamed narrator’s pop star boss Aimee asks her ‘where do you feel most comfortable?’ and she replies ‘The Heath… all my life I’ve taken the paths that lead me back, whether I wanted to or not, to the heath.’ So they pop in a cab and spend the afternoon exploring it, visiting Kenwood House and then ending up in the ladies’ pond.)

Natalie & Nathan stop in the doorway of Jack Straw’s Castle, the highest point of the walk – and indeed just about the highest point in London – then head down towards Archway. But once on the Heath, Natalie becomes steadily more frustrated with Nathan: ‘Leave me alone,’ she tells him. ‘I know where I’m going. I don’t need you to walk me there.’

Natalie & Nathan stop in the doorway of Jack Straw’s Castle, the highest point of the walk – and indeed just about the highest point in London – then head down towards Archway. But once on the Heath, Natalie becomes steadily more frustrated with Nathan: ‘Leave me alone,’ she tells him. ‘I know where I’m going. I don’t need you to walk me there.’

From here they would have crossed the heath almost certainly through the quaint Vale of Health.  The essayist Leigh Hunt lived here from 1816 to 1818 and regularly hosted meetings of writers and poets, who included Shelley, Keats and Byron. There is a plaque to DH Lawrence, who lived at 1 Byron Villas for a year in 1915. Visitors included Bertrand Russell and EM Forster. This was a difficult year for him, with his opposition to the war and the suppression of his novel The Rainbow. The Heath no doubt gave him considerable solace.

The essayist Leigh Hunt lived here from 1816 to 1818 and regularly hosted meetings of writers and poets, who included Shelley, Keats and Byron. There is a plaque to DH Lawrence, who lived at 1 Byron Villas for a year in 1915. Visitors included Bertrand Russell and EM Forster. This was a difficult year for him, with his opposition to the war and the suppression of his novel The Rainbow. The Heath no doubt gave him considerable solace.

Hornsey Lane

‘“Hornsey Lane … This is where I was heading.” That was true. Although it could be said that it did not really become true until the moment she saw the bridge.’

The walk ends at the ‘suicide bridge’ on Hornsey Lane, topped with steel railings to stop people jumping, running sixty feet above the busy dual carriageway that is Archway Road. She had headed here for a purpose but ‘had forgotten that the bridge was not purely functional. She tried her best but could not completely ignore its beauty’.

The walk ends at the ‘suicide bridge’ on Hornsey Lane, topped with steel railings to stop people jumping, running sixty feet above the busy dual carriageway that is Archway Road. She had headed here for a purpose but ‘had forgotten that the bridge was not purely functional. She tried her best but could not completely ignore its beauty’.

She steps on to the ledge, and peers out at London as best the railings allow. This is what she sees, as we do today: ‘The view was cross-hatched. St Paul’s in one box. The Gherkin in another. Half a tree. Half a car. Cupolas, spires. Squares, rectangles, half-moons, stars. It was impossible to get any sense of the whole. From up here the bus lane was a red gash through the city.

‘The tower blocks were the only thing she could see that made any sense, separated from each other, yet communicating. From this distance they had a logic, stone posts driven into an ancient field, waiting for something to be laid on top of them, a statue, perhaps, or a platform.’ It sounds like a proto-Stonehenge in the middle of the city.

But although this is the ‘suicide bridge’ Natalie doesn’t attempt to jump; instead, she abandons Nathan and hurries off after a night bus. The journey is over. In some sense, she is saved. It reminds me of the closing paragraphs of DH Lawrence’s ‘Sons & Lovers’, where Paul Morel steps out into the night-time countryside to ponder his future and is then drawn back in by the lights of Nottingham. ‘But no, he would not give in. Turning sharply, he walked towards the city’s gold phosphorescence.’ Place used as meaning.

But although this is the ‘suicide bridge’ Natalie doesn’t attempt to jump; instead, she abandons Nathan and hurries off after a night bus. The journey is over. In some sense, she is saved. It reminds me of the closing paragraphs of DH Lawrence’s ‘Sons & Lovers’, where Paul Morel steps out into the night-time countryside to ponder his future and is then drawn back in by the lights of Nottingham. ‘But no, he would not give in. Turning sharply, he walked towards the city’s gold phosphorescence.’ Place used as meaning.

We also, with rather less drama, finish our journey.

OTHER STUFF

- Eat: Ackee and saltfish (Jamaica’s national dish) at Emmanuel Caribbean, 233 Willesden High Road

- Watch: Penguin Books’ short videos of ‘Zadie Smith’s Tour of NW’ on YouTube

- Pass by: Zadie’s birthplace, just opposite Brondesbury Park tube and her primary school, Malorees Junior School, a few yards further on down Christchurch Avenue.

7th January 2023 at 9:51 pm

tiny correction if I may: Brondesbury Park is not a tube station, it’s on the Overground line running from Richmond and from Clapham Junction to Stratford.

‘When I were a lad’ the overground ran from Richmond to Broad Street (Liverpool Street). Sometimes I’d get off the train, walk to the very end of the platform and climb over the fence into our back garden. Wasn’t worth the scratches …..

Before 1992 the bus route was the nr8 to Old Ford. Then it became the 98 to Holborn.