‘Piled deep and massy, close and high; mine own romantic town’ Sir Walter Scott

‘This profusion of eccentricities, this dream in masonry and living rock’ Robert Louis Stevenson

‘Edinburgh is a mad god’s dream’ Hugh MacDiarmid

‘Edinburgh is a hotbed of genius’ Tobias Smollett

‘Edinburgh is alive with words’ Sara Sheridan

‘The place establishes an interest in people’s hearts; go where they will, they find no city of the same distinction’ Robert Louis Stevenson

WRITERS REFERENCED IN WALK

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), Robert Garioch (1909-1981), Ian Rankin (1960-), Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932), Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), Muriel Spark (1918-2006), William McGonagall (1825-1902), JK Rowling (1965-), Robert Burns (1759-96), Robert Fergusson (1750–1774), Edwin Morgan (1920-2010), Alexander McCall Smith (1948-), Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), Compton Mackenzie (1883-1972), JM Barrie (1860-1937).

KEY DATA

- Terrain: pavements, some steep ascents

- Starting point: Edinburgh Waverley Station (EH1 1BB)

- Distance: 7.5 km (4.7 miles)

- Walking time: 2 hrs 11 mins

- OS Map: Can be found online at https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/9611710/Edinburgh-Inspiring-Places

- Facilities: city facilities

AN INSPIRING PLACE

If you love literature, Edinburgh is the place to come. It has more literary associations per mile walked than anywhere else in Britain, surpassing even Oxford or Bloomsbury, its only other possible contenders. In 2004 the city was crowned the world’s very first UNESCO City of Literature.

Even the train station is named after a novel: Scott’s ‘Waverley’. The city was the birthplace of the Scottish Enlightenment; it was also in Edinburgh that the world’s first circulating library was established in 1726; and, in 1768, the first copy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica was published. The city is home to 50 publishing houses; and if bookshops are your thing, you will not be disappointed. And of course, every year the world-famous Edinburgh Festival and the Book Festival further enriches its reputation.

And for the walker, it’s perfect too, as Ian Rankin observed: ‘I love Edinburgh because it is a small city, so very manageable. You can walk almost everywhere. It has all the amenities of a capital city, a fascinating history, gorgeous vistas and landscapes.’ This walk is a cracking walk architecturally as well.

THE WALK

We set out from Edinburgh Waverley Station.

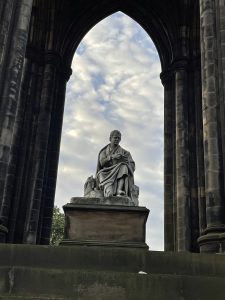

The Scott Monument

The Scott Monument

This vast memorial to Walter Scott was completed in 1844, and if you’re feeling keen you can climb to the top for a sweeping city view. Bill Bryson description of it as looking like a ‘gothic rocket ship’ is very much on the money.

The statue of Scott shows him seated, resting from writing one of his works with a quill pen, his dog Maida by his side. Sixteen heads of Scottish poets and writers appear on the lower faces, and there are many characters depicted from Scott’s novels.

See if you agree with Henry James’ assessment of Princess St: ‘There is no street in Europe more spectacular, it is absolutely operatic.’ (and now of course it finally has that tram!).

Milne’s Bar

Walking up Hanover St, we soon spot Milne’s Bar on our right, which became famous as the ‘Poets’ Pub’ in the 1950s and 1960s, where legendary writers of the ‘Scottish Renaissance’, a modernist movement interlaced with folklore and support of the Gaelic language, gathered in one of the pub’s rooms – which later became known as the ‘Little Kremlin’ (still there) – to discuss politics, poetry and art and to carouse.

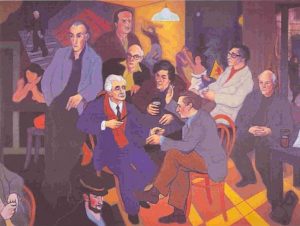

These meetings were immortalised in a painting we get to see later in the National Portrait Gallery entitled ‘Poets’ Pub’ by Alexander Moffat, depicting the eight major poets of the group: Hugh MacDiarmid (centre of the picture and the unofficial leader), Sorley MacLean, Sydney Goodsir Smith, Norman MacCaig, Edwin Morgan, Robert Garioch, George Mackay Brown and Iain Crichton Smith. The setting is an amalgam of the interiors of their favourite drinking haunts: Milne’s Bar, the Abbotsford and the Café Royal. The artist said of his painting: ‘These poets have played the leading role, both in their verse and prose, in shaping the artistic conscience of this country’.

These meetings were immortalised in a painting we get to see later in the National Portrait Gallery entitled ‘Poets’ Pub’ by Alexander Moffat, depicting the eight major poets of the group: Hugh MacDiarmid (centre of the picture and the unofficial leader), Sorley MacLean, Sydney Goodsir Smith, Norman MacCaig, Edwin Morgan, Robert Garioch, George Mackay Brown and Iain Crichton Smith. The setting is an amalgam of the interiors of their favourite drinking haunts: Milne’s Bar, the Abbotsford and the Café Royal. The artist said of his painting: ‘These poets have played the leading role, both in their verse and prose, in shaping the artistic conscience of this country’.

In one of his poems, Robert Garioch describes his anger at having the pub invaded by noisy visitors:

‘Tak me, O Lucifer, frae out this mess.

Hell’s bad, but this is fair abominable’ (Doktor Faust in Rose Street)

The Oxford Bar

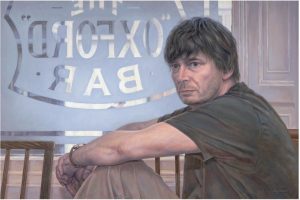

A cramped little pub at the far end of Young St, The Oxford Bar has been made famous as the favourite watering hole of Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh cop, Inspector Rebus.

A cramped little pub at the far end of Young St, The Oxford Bar has been made famous as the favourite watering hole of Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh cop, Inspector Rebus.

Rankin explained his choice: ‘I went along one night, and instantly thought, ‘’This is where Rebus would drink’’. It’s small, hidden away and it seemed to illustrate that hidden, Jekyll and Hyde side of contemporary Edinburgh that I was trying to write about – the Edinburgh that tourists don’t see. There were no bells and whistles, no jukebox – it was very basic – and a lot of coppers drank there at the time.’

Sir Walter Scott’s house

Sir Walter Scott’s house

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) had a property built for his young family at 39 North Castle Street, and they lived here during the winter months from 1802 until financial calamity struck in 1826 due to some disastrous business dealings on his part that forced him to sell up.

During this time he continued to work as an advocate, but in his spare time switched from writing poetry to writing novels, debuting in 1814 with ‘Waverley’, which turned out to be incredibly successful and set the model for historical novels for the next century. The property is now divided into flats, but apparently the gravestone of another of his much-loved dogs dog Camp is still in the garden. He confesses in a letter of 1809: ‘‘I was rather more grieved than philosophy admits of & he has made a sort of blank which nothing will fill up for a long while’.

32 Castle St was the birthplace of Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932), author of ‘The Wind in the Willows’. There is a commemorative plaque on the wall.

32 Castle St was the birthplace of Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932), author of ‘The Wind in the Willows’. There is a commemorative plaque on the wall.

The ‘think-of-a-theme brigade’ has since taken it over, and it is now a badger-themed bar and restaurant called Badger & Co, with the strapline ‘culinary adventures beyond the Wild Wood…’

Princes Street Gardens

Robert Louis Stevenson was buried in Samoa, where he had spent the final years of his life, so there is no grave in his home country. We walk instead past the modest RLS memorial stone in Princes Street Gardens, set amongst a grove of silver birch trees, commissioned by The Stevenson Society in 1987.

We soon see Edinburgh Castle looming high above us. In Rankin’s 2006 book, ‘The Naming of the Dead’, a high-profile politician fell to his death from its craggy peaks.

We soon see Edinburgh Castle looming high above us. In Rankin’s 2006 book, ‘The Naming of the Dead’, a high-profile politician fell to his death from its craggy peaks.

The Grassmarket

For most of its history, the Grassmarket was one of the poorest areas of the city, attracting a transitory population, slum conditions and notorious hangings and murders.

For most of its history, the Grassmarket was one of the poorest areas of the city, attracting a transitory population, slum conditions and notorious hangings and murders.

Some of this reputation still lingered when Muriel Spark wrote her 1961 masterpiece ‘The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie’, set in the 1930s. James Gillespie’s High School in the Marchmont area of Edinburgh, where Muriel Spark grew up, was the model for the school in the novel, where Miss Brodie taught and created an elite group of students called the ‘Brodie Set’.

It was the ‘Brodie Set’ who ventured out with some trepidation into the Old Town: ‘Now they were in a great square, the Grassmarket, with the Castle, which was in any case everywhere, rearing between a big gap in the houses where the aristocracy used to live. It was Sandy’s first experience of a foreign country, which intimates itself by its new smells and shapes and its new poor.’

Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh

Many notable Edinburgh residents are interred at Greyfriars; but the most visited by far is the headstone of Greyfriars Bobby, the faithful Skye terrier who reputedly kept a vigil for 14 years beside his master’s grave.

Many notable Edinburgh residents are interred at Greyfriars; but the most visited by far is the headstone of Greyfriars Bobby, the faithful Skye terrier who reputedly kept a vigil for 14 years beside his master’s grave.

With our literary hats on, we have come to see William McGonagall’s (1825-1902) grave. He is widely celebrated as one of the world’s worst-ever poets. His publisher, who issued the tuppenny pamphlets McGonagall hawked around the streets, proudly advertised him as ‘the greatest bad verse writer of his age … or of any other age’. Stephen Pile in The Book of Heroic Failures writes that McGonagall was ‘so giftedly bad he backed unwittingly into genius’. Spike Milligan had a thing about him. He’s often a name people mention when asked to name famous Scottish poets, so he must have done something right!

With our literary hats on, we have come to see William McGonagall’s (1825-1902) grave. He is widely celebrated as one of the world’s worst-ever poets. His publisher, who issued the tuppenny pamphlets McGonagall hawked around the streets, proudly advertised him as ‘the greatest bad verse writer of his age … or of any other age’. Stephen Pile in The Book of Heroic Failures writes that McGonagall was ‘so giftedly bad he backed unwittingly into genius’. Spike Milligan had a thing about him. He’s often a name people mention when asked to name famous Scottish poets, so he must have done something right!

Well, we will let you be the judge, here are two excerpts from his poem ‘Beautiful Edinburgh’:

‘…And the Castle is wonderful to look upon,

Which has withstood many angry tempests in years bygone;

And the rock it’s built upon is rugged and lovely to be seen

When the shrubberies surrounding it are blown full green.

…Then, all ye tourists, be advised by me,

Beautiful Edinburgh ye ought to go and see.

It’s the only city I know of where ye can wile away the time

By viewing its lovely scenery and statues fine.’

And for those of you who think they have heard the name McGonagall, but can’t quite remember where the answer of course is in Harry Potter. JK Rowling chose the surname for the Professor of Transfiguration, Minerva McGonagall because she had heard of McGonagall and loved the surname. In fact, she probably popped by one day from the Elephant House café for a break from writing, to which we repair next…

The Elephant House

JK Rowling moved to Edinburgh in 1993 and once said of it: ‘Edinburgh is very much home for me and is the place where Harry evolved over seven books and many, many hours of writing in its cafés.’

JK Rowling moved to Edinburgh in 1993 and once said of it: ‘Edinburgh is very much home for me and is the place where Harry evolved over seven books and many, many hours of writing in its cafés.’

Until she became famous, cafés were her writing space: ‘It’s no secret that the best place to write, in my opinion, is in a café. You don’t have to make your own coffee, you don’t have to feel like you’re in solitary confinement and if you have writer’s block, you can get up and walk to the next café while giving your batteries time to recharge and brain time to think. The best writing café is crowded enough to allow you to blend in, but not too crowded that you have to share a table with someone else.’ Or as she said in an interview with Simon Armitage: ‘I really enjoyed being in the world, but in my world simultaneously.’

One of the cafés she frequented the most was this one, where she sat writing in the backroom overlooking the castle. The café also features in Rebus novels as the place where he sometimes meets his nemesis, gangster ‘Big Ger’ Cafferty. The cafe was destroyed by fire in 2021 and, despite plans to re-open, there are no signs it has yet (as of summer 2023). Check before you visit

The Writers’ Museum

The Writers’ Museum in Lady Stair’s Close celebrates the lives of three great Scottish writers – Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson. We peer at portraits, rare books and personal objects including Burns’ writing desk, the printing press on which Scott’s Waverley Novels were first produced, and Scott’s own dining table and rocking horse.

Robert Burns (1759-96), Scotland’s most celebrated poet, lodged in Baxter’s Close nearby (pulled down, but commemorated in a plaque over the entrance to the Writers’ Museum from Lawnmarket) during the winter of 1786-7 to try and find a publisher for the second edition of his poems. But as well as quickly achieving that, he also became the darling of Edinburgh’s literary salons, where he was lauded as ‘this heaven-taught ploughman’. One person who met him at just such a gathering was the 16-year-old Walter Scott, who described him thus:

‘His person was strong and robust; his manners rustic, not clownish, a sort of dignified plainness and simplicity which received part of its effect perhaps from knowledge of his extraordinary talents… there was a strong expression of shrewdness in all his lineaments; the eye alone, I think, indicated the poetical character and temperament.’

His collection included an ‘Address to Edinburgh’, the first stanza of which goes:

EDINA! Scotia’s darling seat!

All hail thy palaces and towers,

Where once beneath a monarch’s feet

Sat Legislation’s sovereign powers!

From marking wildly scattered flowers,

As on the banks of Ayr I strayed,

And singing, lone, the lingering hours,

I shelter in thy honoured shade.

Burns left to posterity a volume of work which, written in his native tongue and championing the common man, has contributed significantly to Scottish identity. Two of his verses which we find ourselves listening to or singing almost every year are of course ‘Auld Lang Syne’ on Hogmanay and ‘Address to a Haggis’ on Burns’ Night.

Makar’s Court

Makars’ Court incorporates quotations from Scottish literature inscribed onto paving slabs. These are just a few of those we read: ‘It’s a grand thing to get leave to live’ (Nan Shepherd, author of The Living Mountain); ‘There are no stars so lovely as Edinburgh street lamps’ (Robert Louis Stevenson); and ‘in simmer, whan aa sorts foregether / in Embro to the ploy.’ (Robert Garioch)

Next, we enter the Royal Mile, which Daniel Defoe was very complimentary about in his ‘Tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain’ (1724-1727): ‘Perhaps the largest, longest, and finest street for buildings and number of inhabitants not in Britain only, but in the World.’ Mind you, you do have to put up with a lot of fellow tourists these days.

The Scottish Storytelling Centre

The Scottish Storytelling Centre (43-45 High St), which opened in 2006, is the world’s first purpose-built modern centre for storytelling. It has a seasonal programme of live storytelling, theatre, music, exhibitions, workshops, and family events; and holds the Scottish International Storytelling Festival each October.

We pop inside and enjoy the experience of an interactive story wall; and we listen to excerpts from Edinburgh’s most famous storyteller, Robert Louis Stevenson.

Chessel’s Court

It was here in 1787 that a robbery took place, masterminded by a certain William Brodie, a Scottish cabinetmaker, deacon of a trades guild and Edinburgh city councillor, who maintained a secret life as a housebreaker, partly for the thrill, and partly to fund his gambling.

It was here in 1787 that a robbery took place, masterminded by a certain William Brodie, a Scottish cabinetmaker, deacon of a trades guild and Edinburgh city councillor, who maintained a secret life as a housebreaker, partly for the thrill, and partly to fund his gambling.

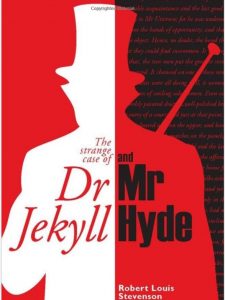

The case that led to Brodie’s downfall came in 1788 when he organised an armed raid on an excise office in Chessel’s Court, which ended in his capture and hanging in the nearby Old Talbooth. Robert Louis Stevenson was fascinated by the dichotomy between Brodie’s respectable façade and his real nature, and it is said that this paradox inspired him to write the novel ‘The Strange Case Of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde’.

Canongate Kirkyard

The economist Adam Smith and the poet Robert Fergusson are buried here.

The economist Adam Smith and the poet Robert Fergusson are buried here.

Best known for his influential work ‘The Wealth of Nations’ which laid the foundations of classical free-market economic theory, Adam Smith (1723-1790) is regarded as the world’s first political economist.

Poet Robert Fergusson (1750–1774) was born nearby, trained as a minister, but abandoned this to take up poetry at the age of 22, principally in the Scottish language. His career was short-lived, and he died in the Edinburgh lunatic asylum.

Fergusson is perhaps best known For ‘Auld Reekie’ (1773) which traces a day in the life of the city.

… Now morn, with bonny purpie-smiles,

Kisses the air-cock o’ St Giles;

Rakin their een, the servant lasses

Early begin their lies and clashes;

Ilk tells her friend o’ saddest distress,

That still she brooks frae scouling mistress;

And wi her joe in turnpike stair

She’d rather snuff the stinking air,

As be subjected to her tongue,

When justly censur’d in the wrong.

In many ways, Robert Fergusson is regarded as the father of Scottish poetry from the Romantic period onwards. Robert Burns was inspired to be a poet by reading his work. He was moved to call Fergusson his ‘elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in the muse’. In 1787, upon learning that Fergusson was buried in an unmarked grave, he paid for a gravestone, penning the inscription which ends:

In many ways, Robert Fergusson is regarded as the father of Scottish poetry from the Romantic period onwards. Robert Burns was inspired to be a poet by reading his work. He was moved to call Fergusson his ‘elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in the muse’. In 1787, upon learning that Fergusson was buried in an unmarked grave, he paid for a gravestone, penning the inscription which ends:

‘…This simple Stone directs Pales Scotia’s way

To pour her Sorrows o’er her Poet’s Dust.’

In a poignant sonnet called ‘At Robert Fergusson’s Grave’, set in the same churchyard in 1962, Edinburgh poet Robert Garioch reflected that ‘here Robert Burns knelt and kissed the mool’ (a clod of earth). Garioch had a strong fellow feeling for Fergusson as a poet whose muse was so firmly set in the daily doings of ‘Auld Reekie’, for they were both born in Edinburgh and made it the subject of many of their verses. Garioch’s poem is also quoted in the opening scene of Alexander McCall Smith’s ‘mystery novel ‘Friends, Lovers, Chocolate’. These Scottish writers are very aware of their literary heritage.

A statue was erected to Robert Fergusson on the pavement at the churchyard entrance in 2004.

Scottish Poetry Library

The Scottish Poetry Library at 5 Crichton’s Close has the laudable aim of bringing the pleasures and benefits of poetry to as wide an audience as possible and is a reminder of how central poetry is to Scottish identity and culture.

The collection houses over 40,000 items, including Scotland’s first Scots Makar (the National Poet for Scotland), Edwin Morgan (1920-2010). He wrote a poem for the Opening of the Scottish Parliament, ‘Open the Doors’, in 2004.

‘…Did you want classic columns and predictable pediments? A growl of old Gothic

grandeur? A blissfully boring box?

Not here, no thanks! No icon, no IKEA, no iceberg, but curves and caverns, nooks

and niches, huddles and heavens, syncopations and surprises. Leave

symmetry to the cemetery.’

You’ll see what he means if you head along to the end of the Royal Mile and look at the building yourself!

Regent Road

The Burns Monument was erected in 1830 and contains a bust of Burns and, reputedly, several relics connected to the poet. As his mother Agnes said: ‘Ah, Robbie, ye asked for bread and they hae gi’en ye a stone.’

The Old Royal High School was founded in 1128 and has educated many of the great figures of the Scottish Enlightenment and literature. It was in this building from 1823 to 1968. Former pupils include Robert Fergusson, William Brodie, Sir Walter Scott, Norman MacCaig, Robert Garioch, William Smellie (founder of the Encyclopaedia Britannica) and Dugald Stewart. Since the school vacated the building in 1968, finding a new use for the Old Royal High School building on Calton Hill has been a major subject of public controversy. The current plan is to house the St Mary’s Music School and the National Music Academy, but funding remains an issue.

Calton Hill, or ‘Edinburgh’s Acropolis’

Calton Hill has panoramic views across the city and boasts a collection of historic monuments. One of the most striking is the National Monument, inspired by the Parthenon in Athens. Also, there is the Nelson monument and The City Observatory, a Greek temple-styled building. Perhaps Alexander McCall Smith’s famous quote about Edinburgh is most evident in this setting: ‘This is a city of shifting light, of changing skies, of sudden vistas. A city so beautiful it breaks the heart again and again.’

We pause at the Dugald Stewart Monument, in a similar style to the Burns Monument. He was a Scottish philosopher and mathematician and became one of the most important figures of the later Scottish Enlightenment. He was also a champion of Robert Burns, to whom he gave a good deal of attention and hospitality when he came to Edinburgh in the winter of 1786 seeking a publisher. We come down off the hill and spin round into Leith Walk.

Leith Walk

The Sherlock Holmes statue faces his creator’s birthplace on Picardy Place, now The Conan Doyle pub. Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) studied medicine at Edinburgh, where the uncanny observational powers of his teacher, Dr Joseph Bell, made him the model for Sherlock Holmes.

In ‘Memories and Adventures’, Arthur Conan Doyle remembers: ‘Stevenson’s last year at Edinburgh University must have just about coincided with my first one, and Barrie must have been in that grey old nest of learning about the year 1876. Strange to think that I probably brushed elbows with both of them in the crowded portal.’ Again, so many links between Scottish writers.

The writer’s territory

44 Scotland St

This is where the prolific Alexander McCall Smith’s (1948-) ‘44 Scotland St’ series is set. The residents and neighbours of 44 Scotland Street come to vivid life in these satirical, perceptive novels, featuring, amongst others, six-year-old Bertie, a remarkably precocious boy; and Pat, a student during her second gap year. Even the real Ian Rankin puts in an appearance.

This is where the prolific Alexander McCall Smith’s (1948-) ‘44 Scotland St’ series is set. The residents and neighbours of 44 Scotland Street come to vivid life in these satirical, perceptive novels, featuring, amongst others, six-year-old Bertie, a remarkably precocious boy; and Pat, a student during her second gap year. Even the real Ian Rankin puts in an appearance.

The point about the street, which we are walking along now (although it has no real 44) is that it is just an incy bit less genteel than the rest of the New Town:

‘The door was somewhat shabby, needing a coat of paint to cover the places where the paintwork had been scratched or chipped away. Well, this was Scotland Street, not Murray Place or Doune Terrace; not even Drummond Place, the handsome square from which Scotland Street descended in a steep slope. This street was on the edge of the Bohemian part of the Edinburgh New Town, the part where lawyers and accountants were outnumbered – just – by others.’

Talking of Drummond Place, that perhaps not surprisingly was the home of the much posher Compton Mackenzie (1883-1972). He lived at No. 31 and became most famous for ‘Whisky Galore (1947). He was also the founder-editor of the Gramophone Magazine in 1923 and in 1928 one of the co-founders of the Scottish National Party along with Hugh MacDiarmid and others. He was president of the Croquet Association from 1953–66, I imagine he would have been able to practice in the spacious Drummond Place Gardens!

JM Barrie (1860-1937)

JM Barrie had his student digs at 14 Cumberland St. He was born into a family of modest means and was one of ten children. He returned regularly during his life and commented on the city; ‘Edinburgh is looking at its best, which is I think the best in the world, for it must be about the most romantic city on earth.’

JM Barrie had his student digs at 14 Cumberland St. He was born into a family of modest means and was one of ten children. He returned regularly during his life and commented on the city; ‘Edinburgh is looking at its best, which is I think the best in the world, for it must be about the most romantic city on earth.’

Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894)

The Stevensons moved to 17 Heriot Row when Robert Louis Stevenson was six years old, and he finally left in 1880. Today the house is a hospitality venue.

As a child, he was prone to illness, especially problems with his lungs and his breathing, and so was rarely allowed to go out into the damp Scottish climate to play with the other children of the neighbourhood.

Directly across the road from the house is Queen Street Gardens, a private garden space, where Stevenson would watch the other children playing, from the safety of the drawing-room on the first floor of the house. Much as he loved the city, he described it as his ‘meteorological purgatory’.

Peering through the railings we can just see a pond with a small island in the centre of it. Was it from watching the children playing around this pond and its island that Stevenson came up with the idea of what became Treasure Island?

Robert Garioch (1909-1981)

4 Nelson St was the adult home of Robert Garioch, an influential member of the Scottish Renaissance and best known for his humorous and satirical poems. There is a bronze plaque to commemorate it.

I like poet Donald Campbell’s epitaph to him: ‘If I learned anything at all from Robert Garioch, it was to do the work as well as I could do it and not worry too much about either the applause of success or the obscurity of failure’.

Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Maybe you feel like a break now, where better than the Scottish National Portrait Gallery where, after a snack, we get to see pictures of Walter Scott, Robert Burns, Adam Smith, Robert Louis Stevenson, Boswell, Muriel Spark, Irvine Walsh, The ‘Poet’s Pub’ Eight and Ian Rankin, posing in the Oxford Bar, amongst many others.

Maybe you feel like a break now, where better than the Scottish National Portrait Gallery where, after a snack, we get to see pictures of Walter Scott, Robert Burns, Adam Smith, Robert Louis Stevenson, Boswell, Muriel Spark, Irvine Walsh, The ‘Poet’s Pub’ Eight and Ian Rankin, posing in the Oxford Bar, amongst many others.

We pass through St Andrew’s Square and, in case you haven’t had enough of William McGonagall’s ‘Beautiful Edinburgh’, here’s another stanza:

‘Lord Melville’s Monument is most elegant to be seen,

Which is situated in St. Andrew’s Square, amongst shrubberies green,

Which seems most gorgeous to the eye,

Because it is towering so very high.’

We have encountered so many great literary figures on our walk, and as we end it we are reminded of the two who perhaps achieved the greatest acclaim in their lifetime: first Walter Scott celebrated with the towering monument that we have glimpsed from many streets back, a beacon within the city; and then finally, as we glance up at the towering Balmoral Hotel, we recall that JK Rowling retreated here to finish her final Harry Potter book, ‘Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows’ as she had become too famous to sit unnoticed in Edinburgh’s cafés. We know that she stayed in Room 552 because she scribbled on a marble bust of the god Hermes ‘JK Rowling finished writing Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in this room on 11th Jan 2007’, which is still there; and the room has been re-named the JK Rowling suite and no doubt the tariff rate has skyrocketed since.

And this too is where we finish our story.

OTHER STUFF

- Book: The Edinburgh Book Lovers’ Tour at https://www.edinburghbooktour.com/ , created by Allan Foster.

- Sign-up: to the Edinburgh Literary Pub Tour at http://www.edinburghliterarypubtour.co.uk/ , performed by professional actors.

- Sign-up: to an Ian Rankin Rebus Tour at https://rebustours.com/

- Sign-up: to a Leith, Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting Tour at https://www.leithwalks.co.uk/

- Download: an interactive map of Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh at https://www.ianrankin.net/landing-page/ian-rankin/ian-rankin-extras/ian-rankin-edinburgh/

- Buy: ‘Book Lovers’ Edinburgh, A Guide and Companion’ (2018), by Allan Foster

- Explore: Edinburgh’s mysterious book sculptures; find a map at https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Book-Sculptures-Map-FINAL-screen.pdf

- Attend: The Edinburgh International Festival, in August each year, but plan way ahead! https://www.eif.co.uk/

- Browse: There are more Edinburgh bookshops than space allows, though notable mentions include Old Town Bookshop (8 Victoria Street), Word Power (West Nicholson Street) and Elvis Shakespeare (347 Leith Walk), Armchair Books (West Port Street).

- Attend: The Edinburgh International Book Festival in Charlotte Square, August, details at https://www.edbookfest.co.uk/

DIRECTIONS

- Start at the Scott Monument in Princess St and head southwest until you reach Hanover St, where you turn right

- Turn second left into George St, right into Frederick St, left into Hill St, right into N Castle St, entering West Princes St Gardens; head down left to the Ross Fountain, then bear right past the Robert Louis Stevenson memorial and then cross the railway lines (in a tunnel) to exit at the south end of the Mound

- Turn right up the Mound, right into Mound Place which becomes Ramsay Lane, reaching Castlehill, where you turn left

- On reaching the roundabout, head southeast down Upper Bow, then down some steps to Victoria St and W Bow, reaching Grassmarket

- Exit left along Cowgatehead, then right at the roundabout along Candlemaker Row; shortly, turn right through a stone arch into Greyfriars, and walk up through the graveyard to the church and Bobby’s grave

- Exit onto Greyfriars, then turn left along George IV Bridge Rd, and turn right into the High St, which becomes Canongate (all known as the Royal Mile)

- Shortly after Canongate Kirkyard, turn left under a concrete arch (Lochend Close) to reach Lochend Close Rd

- Cross Calton Rd and take the footpath climbing up to Regent Rd, where you turn left and then cross the road to turn right opposite the Scottish Government art deco building up the steps to Calton Hill

- At the top of the steps, head towards the Acropolis and then take the path to the left of it that leads down to the Royal Terrace

- Head left here to reach the roundabout, where you take the left down Leith Walk, and then right into Broughton St and left into York Lane, which continues as Dublin St Lane S. At the T-junction turn right up Dublin St to reach Drummond Place, which you circumnavigate, exiting south via Nelson St, which you follow to Abercromby Place

- Turn right in Abercromby Place, left into Queen St Gardens east and then left along Queen St, passing the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

- Shortly after this, turn right down N St Andrews St and then cross St Andrew Square diagonally southwest to S St David St; then head south back to the Scott Monument and the start.

Leave a Reply