‘Mere seeing from a distance did not satisfy her; she longed to go alone far into the fields and hear the birds singing, the brooks tinkling, and the wind rustling through the corn, as she had when a child. To smell things and touch things, warm earth and flowers and grasses, and to stand and gaze where no one could see her, drinking it all in.’

The Inspiration for this walk…a book languishing on the bookshelf

I must confess this was on my reading list of books to be read before going up to University to do my English degree. But in fact, I only read it forty-five years after that – and just kicked myself that I hadn’t read it before. It is such a joy, so observationally acute and yet so understated, less melodramatic than Hardy or Lawrence and more real for that. The only book I would immediately compare it to is Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield; he presumably must have read it and been inspired. In a way, both books are better described as observations than novels.

I must confess this was on my reading list of books to be read before going up to University to do my English degree. But in fact, I only read it forty-five years after that – and just kicked myself that I hadn’t read it before. It is such a joy, so observationally acute and yet so understated, less melodramatic than Hardy or Lawrence and more real for that. The only book I would immediately compare it to is Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield; he presumably must have read it and been inspired. In a way, both books are better described as observations than novels.

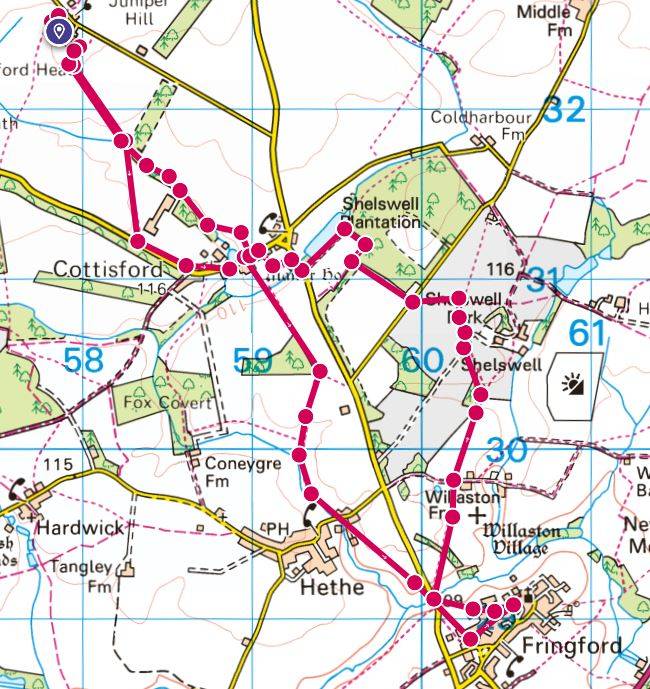

KEY DATA

- Terrain: easy going

- Starting point: Juniper Hill, North Oxfordshire, NN13 5RH

- Distance: 11 km (6.9 miles)

- Walking time: 2 hrs 53 mins

- Facilities: Butcher’s Arms in Fringford (OX27 8EB)

The map can be found at: https://explore.osmaps.com/route/17766826/lark-rise-to-candleford-green?lat=51.973007&lon=-1.156110&zoom=13.1257&style=Standard&type=2d

FLORA THOMPSON (1876-1947)

Lark Rise to Candleford is a trilogy of semi-autobiographical novels about the countryside of north-east Oxfordshire at the end of the nineteenth century, first published together in 1945. The stories were previously published separately as Lark Rise in 1939, Over to Candleford in 1941 and Candleford Green in 1943.

The stories relate to three communities: the hamlet of Juniper Hill (Lark Rise), where Flora grew up; the nearby village of Fringford (Candleford Green), where Flora got her first job in the Post Office; and an amalgam of larger local towns including Bicester and Buckingham which collectively she called Candleford.

Because Thompson wrote her account some forty years after the events, she was able to identify the period as a pivotal point in rural history: the time when the quiet, close-knit rural culture, governed by the seasons, began a transformation, through agricultural mechanisation, better communications and urban expansion, into the homogenised society of today. The transformation is not explicitly described. It appears as an allegory, for example in Laura’s first visit to Candleford without her parents; the journey from her tiny village to the sophisticated town representing the temporal changes that would affect her whole community.

Although the works are autobiographical, Thompson distances herself from her childhood persona by telling the tale in the third person; she appears in the book as Laura Timmins, rather than her actual maiden name of Flora Timms. This device allows Thompson to comment on the action, using the voice of Laura as the child she was and as the adult narrator, without imposing herself onto the work.

Flora was, almost uniquely, able to write from her own experience, giving an authoritative account of some of the hardships and pleasures of rural life in the period that she grew up. Rural life, as she describes it, feels very believable and unembroidered. She hoped that they might adapt ‘the best of the new to their own needs while still retaining those qualities and customs which have given country life its distinctive character’.

Footpaths thread in and out of the story of Lark Rise, as the hamlet women watch for the postman, or the vicar’s daughter, to come over the allotment stile; as the paths are used for mushrooming or going to work, for every type of country business or pleasure. The paths provide connectivity between communities. Flora herself was a keen walker throughout her life – when she moved down to Hampshire she walked up to twenty miles a day.

OUR WALK

Juniper Hill (Lark Rise in the novel)

Our walk begins in Juniper Hill, where Flora Thompson was born in 1876. Flora describes it thus:

‘The hamlet stood on a gentle rise in the flat, wheat-growing north-east corner of Oxfordshire. We will call it Lark Rise because of the great number of skylarks which made the surrounding fields their springboard and nested on the bare earth between the rows of green corn.

‘All around, from every quarter, the stiff, clayey soil of the arable fields crept up, bare, brown and windswept for eight months out of the twelve. Spring brought a flush of green wheat and there were violets under the hedges and pussy-willows out beside the brook at the bottom of the ‘Hundred Acres’, but only for a few weeks in later summer had the landscape real beauty. Then the ripened cornfields rippled up to the doorsteps of the cottages and the hamlet became an island in a sea of dark gold.

‘To a child it seemed that it must always have been so; but the ploughing and sowing and reaping were recent innovations. Old men could remember when the Rise, covered with juniper bushes, stood in the midst of a furzy heath – common land which had come under the plough after the passing of the Enclosure Acts. Some of the ancients still occupied cottages on land which had been ceded to their fathers as ‘squatters’ rights’, and probably all the small plots upon which the houses stood had originally been so ceded.

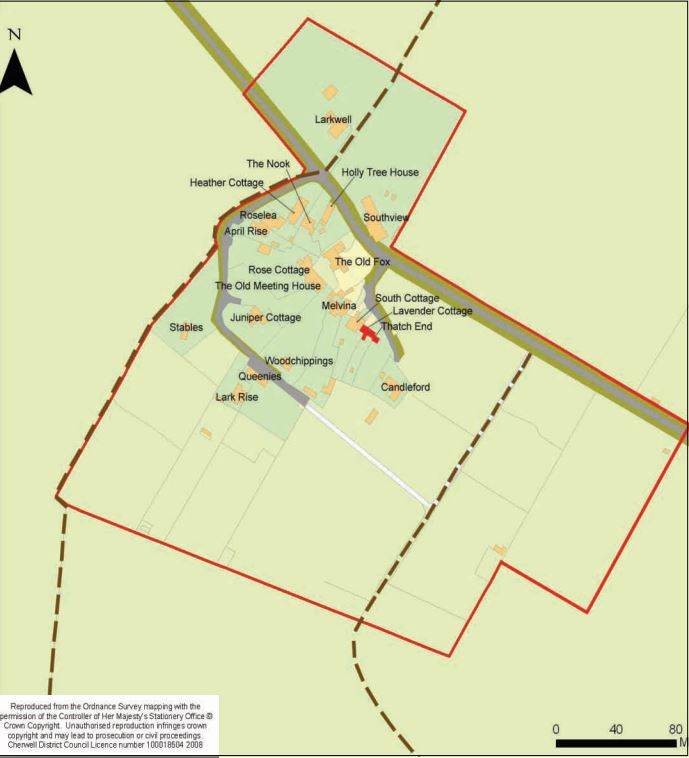

‘In the eighteen-eighties the hamlet consisted of about thirty cottages and an inn, not built in rows, but dotted down anywhere within a more or less circular group. A deeply rutted cart track surrounded the whole, and separate houses or groups of houses were connected by a network of pathways. Going from one part of the hamlet to another was called ‘going round the Rise’.

‘A road flattened the circle at one point. It had been cut when the heath was enclosed, for convenience in fieldwork and to connect the main Oxford road with the mother village and a series of other villages beyond. From the hamlet it led on the one hand to church and school, and on the other to the main road, or the turnpike, as it was still called, and so to the market town where the Saturday shopping was done.’

Flora’s family house was called the End House; she said of it ‘it looked as if it was going to get up and run away into the fields’. We can still see it today, re-named Lark Rise Cottage, on the south side of the village looking across the fields, albeit the house has been much enlarged and changed. There is a plaque to Flora Tompson on the side of it.

Flora’s family house was called the End House; she said of it ‘it looked as if it was going to get up and run away into the fields’. We can still see it today, re-named Lark Rise Cottage, on the south side of the village looking across the fields, albeit the house has been much enlarged and changed. There is a plaque to Flora Tompson on the side of it.

Just to the northeast of it is Queenie’s House, still called that today. She is a much-loved character in the book. Queenie is one of Lark Rise’s older residents and in many ways is the matriarch of the village. As well as looking after her bees, she was notable for her lacemaking and her adherence to the older ways of the country.

Just to the northeast of it is Queenie’s House, still called that today. She is a much-loved character in the book. Queenie is one of Lark Rise’s older residents and in many ways is the matriarch of the village. As well as looking after her bees, she was notable for her lacemaking and her adherence to the older ways of the country.

Cottisford (Fordlow in the novel)

The tiny village of Cottisford is a mile and a half southeast of Juniper Hill, and it was here that Flora and her siblings went to school and church.

From Juniper Hill, we take the footpath across the fields to Cottisford. This must have been the route she took when she was trying to protect her younger brother from being teased on the way to school:

‘It was all cross-country going; over footpaths and stiles, through spinneys and past villages…The little brother got stones in his shoes, and all their feet felt tired from the rough travelling and the stiff mud which caked their insteps.’

But the usual route to school that most of the children took was along what is now the tarmacked road:

‘Up the long, straight road they straggled, in twos and threes and in gangs, their flat, rush dinner-baskets over their shoulders and their shabby little coats on their arms against rain. In cold weather some of them carried two hot potatoes which had been in the oven, or in the ashes, all night, to warm their hands on the way and to serve as a light lunch on arrival.

‘They were strong, lusty children, let loose from control; and there was plenty of shouting, quarrelling, and often fighting among them. In more peaceful moments they would squat in the dust of the road and play marbles or sit on a stone heap and play dibs with pebbles, or climb into the hedges after birds’ nests or blackberries, or to pull long trails of bryony to wreathe round their hats. In winter they would slide on the ice on the puddles, or make snowballs – soft ones for their friends, and hard ones with a stone inside for their enemies.

‘After the first mile or so the dinner-baskets would be raided; or they would creep through the bars of the padlocked field gates for turnips to pare with the teeth and munch, or for handfuls of green pea shucks, or ears of wheat, to rub out the sweet, milky grain between the hands and devour. In spring they ate the young green from the hawthorn hedges, which they called ‘bread and cheese’, and sorrel leaves from the wayside, which they called ‘sour grass’, and in autumn there was an abundance of haws and blackberries and sloes and crab apples for them to feast upon. There was always something to eat, and they ate, not so much because they were hungry as from habit and relish of the wild food.’

It would have taken them at least half an hour to reach school given all these diversions. This is how Cottisford village is described:

‘

‘A little, lost, lonely place, much smaller than the hamlet, without a shop, an inn, or a post office, and six miles from a railway station. The little squat church (now with a plaque to Flora Thomson in it), without spire or tower, crouched back in a tiny churchyard that centuries of use had raised many feet above the road, and the whole was surrounded by tall, windy elms in which a colony of rooks kept up a perpetual cawing.

‘Next came the Rectory, so buried in orchards and shrubberies that only the chimney stacks were visible from the road; then the old Tudor farmhouse with its stone, mullioned windows and reputed dungeon. These, with the school and about a dozen cottages occupied by the shepherd, carter, blacksmith, and a few other superior farmworkers, made up the village.

‘Even these few buildings were strung out along the roadside, so far between and so sunken in greenery that there seemed no village at all. It was a standing joke in the hamlet that a stranger had once asked the way to Fordlow after he had walked right through it. The hamlet laughed at the village as ‘stuck up’; while the village looked down on ‘that gipsy lot’ at the hamlet.’

As we walk along the road into the village Flora’s description could almost have been penned today.

Flora describes the school thus: ‘Fordlow National School was a small grey one-storied building, standing at the cross-roads at the entrance to the village. The one large classroom which served all purposes was well lighted with several windows, including the large one which filled the end of the building which faced the road. Beside, and joined on to the school, was a tiny two-roomed cottage for the schoolmistress, and beyond that a playground with birch trees and turf, bald in places, the whole being enclosed within pointed, white-painted palings.’

Flora describes the school thus: ‘Fordlow National School was a small grey one-storied building, standing at the cross-roads at the entrance to the village. The one large classroom which served all purposes was well lighted with several windows, including the large one which filled the end of the building which faced the road. Beside, and joined on to the school, was a tiny two-roomed cottage for the schoolmistress, and beyond that a playground with birch trees and turf, bald in places, the whole being enclosed within pointed, white-painted palings.’

Fringford (known in the novel as Candleford Green)

Flora Thompson worked in the village post office here from the age of 14, between 1891 and 1897.

Flora Thompson worked in the village post office here from the age of 14, between 1891 and 1897.

She writes: ‘Candleford Green was but a small village and there were fields and meadows and woods all around it. As soon as Laura crossed the doorstep, she could see some of these. But mere seeing from a distance did not satisfy her; she longed to go alone far into the fields and hear the birds singing, the brooks tinkling, and the wind rustling through the corn, as she had when a child. To smell things and touch things, warm earth and flowers and grasses, and to stand and gaze where no one could see her, drinking it all in.’

Laura loved the garden behind the post office: ‘There Laura spent many happy hours, supposed to be picking fruit for jam, but for the better part of the time reading or dreaming. One corner, overhung by a Samson tree and walled in with bushes and flowers, she called her ‘green study’.’

The best clue to finding the Old Post Office is an old AA sign on the front of the building. The church also has a plaque to Flora.

Shelswell Park (known in the novel as Skeldon Park)

Shelswell Park reminds me a bit of the Queen Vic pub in EastEnders or the Rovers Return Inn in

Coronation Street – it’s where the plot tends to develop, or in this case, it marks the early life stages of Laura: her childhood, her first job and her first romantic encounter.

Coronation Street – it’s where the plot tends to develop, or in this case, it marks the early life stages of Laura: her childhood, her first job and her first romantic encounter.

Sadly what we see on our walk today is only a remnant of what had been there. Flora would have seen an impressive Italianate country house designed by the architect William Wilkinson. By the 1950s the house was unoccupied and falling into disrepair; and all that is left of it today is the Coach House (picture on right), which is hired out for weddings and events.

At the celebrations in the park for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, Flora wrote:

‘There were more people in the park than the children had ever seen before, and the roundabouts, swings and coconut shies were doing a roaring trade. Tea was taken in a huge marquee in relays, one parish at a time, and the sound of the brass band, roundabout hurdy-gurdy, coconut thwacks, and showmen’s shouting surged around the frail, canvas walls like a roaring sea.

‘After tea there were sports, with races, high jumps, dipping heads into tubs of water to retrieve sixpences with the teeth, grinning through horse collars….

‘The local gentlepeople promenaded the ground in parties; stout, red-faced, raising their straw hats to mop their foreheads; hunting ladies, incongruously garbed in silks and ostrich-feather boas; young girls in embroidered white muslin and boys in Eton suits…

‘All the way home in the twilight, the end house party could hear the popping of fireworks behind them and, turning, see rockets and showers of golden rain above the dark treetops. Al last, standing at their own garden gate, they heard the roaring of cheers from hundreds of throats and the band playing ‘God save the Queen’.’

First job

The second time Laura visited Shelswell Park was when she was fourteen when she went to work for Mrs Fritton. Before she was permitted to handle a letter in the Post Office she had to be sworn in before a Justice of the Peace – in this case Edward Slater-Harrison of Shelswell. She describes it thus:

‘The interview next morning did not turn out so terrifying as Laura had expected. Sir Timothy smiled very kindly upon her when the footman ushered her into his Justice Room, saying: ‘The young person from the Post Office, please, Sir Timothy.’

‘What have you been up to? Poaching, rick-burning, or petty larceny?’ he asked when the footman had gone. ‘If you’re as innocent as you look, I shan’t give you a long sentence. So come along,’ and he drew her by the side of his chair. Laura smiled dutifully, for she knew by the twinkle of his keen blue eyes beneath their shaggy white eyebrows that Sir Timothy was joking.

‘As she leaned forward to take up a pen with which to sign the thick blue official document he was unfolding, she sensed the atmosphere of jollity, good sense, and good nature, together with the smell of tobacco, stables, and country tweeds he carried around like an aura.

‘But read it! Read!’ he cried in a shocked voice. ‘Never put your name to anything before you have read it or you’ll be signing your own death warrant one of these days.’ And Laura read out, as clearly as her shyness permitted, the Declaration which even the most humble candidate for Her Majesty’s Service had in those serious days to sign before a magistrate.

‘I do solemnly promise and declare that I will not open or delay or cause or suffer to be opened or delayed any letter or anything sent by the post’, it began, and went on to promise secrecy in all things.

‘When she had read it through, she signed her name. Sir Timothy signed his, then folded the document neatly for her to carry back to Miss Lane, who would send it on to the higher authorities.’

First romantic encounter

It was when Flora was walking in the grounds of Shelswell Park in the course of her duties that she had an encounter with a young gamekeeper, armed with a shotgun, who accused her of trespassing

‘She went in and out of the copses, gathering bluebells or wild cherry blossom, or hunting for birds’ nests, and never saw any one, until one May morning of her second year on the round. She had gone into one of the copses where a few lilies-of-the-valley grew wild, found half a dozen or so, and was just climbing down the high bank which surrounded the copse when she came face to face with a stranger. He was a young man in rough country tweeds and carried a gun over his shoulder. She thought for a moment that he might be one of Sir Timothy’s nephews, or some other visitor at the great house, though, of course, she should have remembered that no guest of Sir Timothy’s would have carried a gun at that season. But, when he pointed to a notice board which said Trespassers will be prosecuted and asked, rather roughly, what the devil she thought she was doing there, she knew he must be a gamekeeper, and he turned out to be a new underkeeper engaged to do most of the actual work of the old man, who was failing in health, but refused to retire.

‘He was a tall, well-built young man, apparently in the middle twenties, with a small fair moustache and very pale blue eyes which, against his dark tanned complexion, looked paler. His features might have been called handsome but for their set rigidity. These softened slightly when Laura held out her half-dozen lilies-of the-valley as an excuse for her trespass. He was sure she had meant to do no harm, he said, but the pheasants were still sitting and he could not have them disturbed. There had been too much of this trespassing lately – Laura wondered by whom – too much laxity, too much laxity, he repeated, as if he had just thought of the word and was pleased with it, but it had got to stop. Then, still walking close on her heels on the narrow path, as if to keep her in custody, he asked her if she would tell him the way to Foxhill Copse, as it was his first morning on the estate and he had not grasped the lie of the land yet. When she pointed it out and he saw that her own path led past it, he unbent sufficiently to suggest that they should walk on together.’

The relationship did not progress beyond a kiss, in the end, Philip’s self-certainty and lack of empathy was not to Laura’s liking.

Our walk returns once again via Cottisford, and we take a slightly different footpath back to Juniper Hill.

OTHER STUFF

- Watch: The BBC series of Lark Rise to Candleford, which ran for five series from 2008 to 2011

- Watch: Lark Rise to Candleford by Martin Greenwood (2011) on YouTube

- Read: The Real Candleford Green, Martin Greenwood (2016); The World of Flora Thompson Revisited, Christine Bloxham (2007)

- Read: Dream of the Good Life (2014), Richard Mabey – very readable and illuminating, although Flora’s real character proves very elusive.

- Follow the excellent Literary walk based around Liphook, where she lived in later life. You can find it at: https://www.visit-hampshire.co.uk/things-to-do/flora-thompson-circular-walk-p399171

Leave a Reply