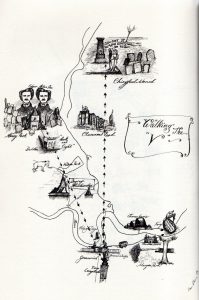

‘Walking is the best way to explore and exploit the city; the changes, shifts, breaks in the cloud helmet, movement of light on water.’

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Park & pavement

- Start: Stoke Newington Overground, N16 6YA

- Finish: Dockland Light Railway – Cutty Sark for Maritime Greenwich, SE10 9ED

- Distance: 14.7 km (9.2 miles)

- Walking time: 3 hr 46 mins

- Map: Can also be found online at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10575707/Inspiring-Places-Londone-East-End

- Facilities: Shops and pubs along the way

Writers of the Human Condition and anti- establishmentarians

The East End seems to have been a haven for anti-establishmentarians, nurturing a long line of writers who definitely don’t toe the line and look at the world in a very different way from the traditionalists and romantics.

Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) was a larger-than-life character, a trader, writer, journalist, political pamphleteer and spy. He wrote things as he saw them, and above all he was a rationalist. For many years he was holed up in Stoke Newington, apparently hiding from his creditors.

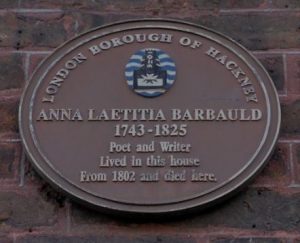

Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825) was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and author of children’s literature. With her first publication, a slender volume titled Poems (1773), she established her name. She moved to Stoke Newington in 1802 and lived there for the rest of her life.

She was an innovative writer of works for children. Her literary career spanned numerous periods in British literary history: her work promoted the values of the Enlightenment and of sensibility, while her poetry made a founding contribution to the development of British Romanticism. Barbauld was also a literary critic. ‘British Novelists’ (1810), an anthology of 18th-century novels helped to establish the canon as it is known today.

Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) was confined to the German Hospital in Dalston on his return from Africa. ‘Heart of Darkness’, which he wrote whilst he was here, makes a stark criticism of the systematic abuse and exploitation of the world’s indigenous inhabitants. It is – at its dark heart – a bitter critique of imperialism, which Conrad condemns as ‘a rapacious and pitiless folly’.

George Orwell (1903-1950) was also very preoccupied with the underbelly of society, and almost all his work had a political slant. In the late 1920s he wrote about the hardships of the life of homelessness on the road, and to immerse himself in the experience he lived as a tramp. On his first outing in 1927, he set out from Limehouse Causeway, spending his first night in the casual ward of a workhouse, known as a ‘Spike’. He recorded his experiences of this in ‘The Spike’, and this went on to inform part of his famous novel ‘Down & Out in Paris and London’ (1933).

Iain Sinclair (1943-) who lives near London Fields, became the (unintentional) father of a whole new genre of literature devoted to psychogeography, using walking, often at random, as a way of experiencing and understanding a city in its ‘unadorned and unrehearsed’ state, the bad bits as valid as the good bits to the overall experience. Much of his writing has a political undertone too, bemoaning the ‘rape’ of the East End by capitalism.

In 1997 he wrote ‘Lights Out For The Territory, 9 excursions in the Secret History of London’, connecting people and places, redrawing boundaries both ancient and modern, reading obscure signs and finding hidden patterns. His work has been described as ‘social surrealism’. The route we are taking today is his first chapter, ‘Skating On Thin Eyes: The First Walk’, from Abney Park Cemetery to Greenwich, a ‘near-arbitrary route’ as he describes it.

In 1997 he wrote ‘Lights Out For The Territory, 9 excursions in the Secret History of London’, connecting people and places, redrawing boundaries both ancient and modern, reading obscure signs and finding hidden patterns. His work has been described as ‘social surrealism’. The route we are taking today is his first chapter, ‘Skating On Thin Eyes: The First Walk’, from Abney Park Cemetery to Greenwich, a ‘near-arbitrary route’ as he describes it.

Sinclair states his aim at the start of the book: ‘The notion was to cut a crude V into the sprawl of the city, to vandalise dormant energies by an act of ambulant sign making. To walk out from Hackney to Greenwich Hill, and back along the River Lea to Chingford Mount, recording and retrieving the messages on walls, lampposts, doorjambs: the spites and spasms of an increasingly deranged populace. Dynamic shapes, with ambitions to achieve a life of their own, quite independent of their supposed author. Railway to pub to hospital: trace the line on the map. These botched runes, burnt into the script in the heat of creation, offer an alternative reading – a subterranean, preconscious text capable of divination and prophecy.’

THE WALK

Iain Sinclair has lived in Albion Drive for over forty years, and his first excursion sets out from here. We re-order the first part just a little and start in Abney Park Cemetery.

Abney Park Cemetery

In the early 1800s, London’s rapid population growth proved too much for inner-city burial grounds, which were literally overflowing. Parliament passed a bill in 1832 to encourage the establishment of new private cemeteries. Within ten years, seven had been established (later dubbed ‘The Magnificent Seven’), one of which was Abney Park, which became a haven for non-conformists.

In the 1970s, the cemetery fell into disrepair and was abandoned, allowing a uniquely wild atmosphere to develop at the site. This urban wilderness is now carefully managed, making it a great place to walk through. Famous tombs include those of General William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army; and Dr Isaac Watts, English hymn-writer.

We enter through the glorious Egyptian revival entranceway, with hieroglyphics signifying ‘The gates of the Abode of the Mortal Part of Man’. Sinclair comments: ‘Through those Egyptian pylons and inside the cemetery walls, Poe’s wilderness of oak and chestnut, swamp cypress, thistle…’

We enter through the glorious Egyptian revival entranceway, with hieroglyphics signifying ‘The gates of the Abode of the Mortal Part of Man’. Sinclair comments: ‘Through those Egyptian pylons and inside the cemetery walls, Poe’s wilderness of oak and chestnut, swamp cypress, thistle…’

‘We had brought ourselves to the heart of it, the vandalised chapel in the woods, and we were confronted by just the reversal we deserved. DOG. The word twisted our expedition back to its source. It established this site as the X, the given, the point from which the true walk would begin.’ This is Abney Cemetery Chapel, looking like a miniature cathedral and fairly recently restored. So for us of course this also represented the official start of our walk.

We came out of the cemetery at the south gate. Just opposite and slightly to the right, at the junction with Defoe Rd, is No. 95 Newington Church Street, where on the side there is a blue plaque to Daniel Defoe, who lived in a house on this site for the last 20 years of his life. ‘Robinson Crusoe’ was written here, inspired by the son of a neighbour who had been shipwrecked in Madagascar aged 16, and was only rescued 14 years later.

Next, we pass 113 Church Street, where there is a brown plaque on the first floor to Anna Laetitia Barbauld. She had arrived in 1802 with her husband, who took over the pastoral duties of the Unitarian Chapel at Newington Green, a mile away. He subsequently became deranged and drowned himself in the nearby New River in 1808.

Next, we pass 113 Church Street, where there is a brown plaque on the first floor to Anna Laetitia Barbauld. She had arrived in 1802 with her husband, who took over the pastoral duties of the Unitarian Chapel at Newington Green, a mile away. He subsequently became deranged and drowned himself in the nearby New River in 1808.

Like Defoe, who had lived just a few doors up from her, Barbauld was a Protestant Dissenter. His novel Robinson Crusoe is included in the ‘British Novelists’ collection, and in the introduction to it she writes ‘it yields to few in the truth of its description and its power of interesting the mind’. She also mentions the trouble he got into with the establishment for expressing his political views in print, and I imagine she must have felt a considerable affinity with him, especially after she published ‘Eighteen Hundred and Eleven’ during the Napoleonic wars, which was lambasted as unpatriotic. She basically saw England as a post-war ruin, and she protested vehemently about the British involvement in the war. The reviews of this poem were so vicious that she decided to lay down her pen for the rest of her life. She nonetheless remained an inspiration for later female writers, including Elizabeth Benger, Joanna Baillie and Mary Robinson.

I love these lines from an Ode to a Caterpillar:

‘No, helpless thing, I cannot harm thee now;

Depart in peace, thy little life is safe,

For I have scanned thy form with curious eye,

Noted the silver line that streaks thy back,

The azure and the orange that divide

Thy velvet sides; thee, houseless wanderer,

My garment has enfolded, and my arm

Felt the light pressure of thy hairy feet;

Thou hast curled round my finger; from its tip,

Precipitous descent! with stretched out neck,

Bending thy head in airy vacancy,

This way and that, inquiring, thou hast seemed

To ask protection; now, I cannot kill thee.’

(composed in 1816, and you could imagine observed in Abney Park cemetery)

We continue to head east along Stoke Newington Church St, popping briefly into Stoke Newington library to see the statue of Defoe displayed there; then south along ‘Stoke Newington Road stretch(ing) onwards like the rubber neck of a chicken’…

Anglo-Irish visual artist and poet Tom Raworth lived on Amhurst Road, further down on our left, in the 1960s. Raworth was a pioneer of experimental modernist poetry, and as a publisher, he brought the works of American poets such as Allen Ginsberg to Britain.

Sinclair writes: ‘It was from Amhurst Road that the poet Tom Raworth operated his revolutionary matrix press. The press was revolutionary in terms of its quality, its quick-witted intelligence, the unfussy but enticing look of the thing.’

Dalston Junction: ‘The quadrivium, or meeting place of four roads, is the spiritual centre of the area through which we are walking: it’s where suicides and vampires would receive their toothpick through the heart. On the east/west axis, the hobbled spurt of Dalston Lane, labouring gamely under the burden of cultural significance imposed upon it by Patrick Wright in A Journey Through Ruins, goes head-to-head with Peter Sellers’ comedic Balls Pond Road. And to the north, Ermine Street, lightly disguised as Kingsland High Street (Stoke Newington Road), makes a bid for Stamford Hill, White Hart Lane, Cambridge and other inconsequential destinations.’

Dalston Lane becomes Graham Rd, and down Clifton Rd on the left is The German Hospital, where Joseph Conrad wrote ‘Heart of Darkness’ whilst he was convalescing after falling ill in the Congo. As Sinclair writes: ‘After he’d made his trip up the river, he came back to the German Hospital in a state of collapse, with journals and photographs of that trip. Essentially Heart of Darkness is cooked up in Dalston.’

Dalston Lane becomes Graham Rd, and down Clifton Rd on the left is The German Hospital, where Joseph Conrad wrote ‘Heart of Darkness’ whilst he was convalescing after falling ill in the Congo. As Sinclair writes: ‘After he’d made his trip up the river, he came back to the German Hospital in a state of collapse, with journals and photographs of that trip. Essentially Heart of Darkness is cooked up in Dalston.’

We continue heading south down Kingsland Rd. Sinclair reflected on it: ‘We stuck to the line of shops on the east side… Kingsland Road was a furious river of competing voices: West African enterprise (an optician who doubled as a copier of legal documents), Fax bureaux, exotic cake shops, a mini-cab firm with a radio beacon tall enough to endanger lowflying aircraft, Turkish football club poolrooms, schmutter merchants, and the entire range of multi-ethnic snack bars and fast food emporia.’ That still describes it well more than twenty years later.

‘We swing (off) the main drag (Kingsland Road) without paying our respects to the pub on the corner, The Fox (372 Kingsland Rd), whose former landlord, Clifford Saxe, a commercial associate of the Knight dynasty, is said to have planned the £8 million-pound 1976 robbery of the Bank of America from the room upstairs. Mr Saxe is one of the Famous Five (along with Ronnie Knight, Frederick Foreman, Ronald Everett, John James Mason) who opted for early retirement in the sun.’

Stonebridge Gardens: ‘At the end of Albion Square (in the park by the Duke of Wellington pub), beyond the clutch of houses that have been built over the Nimby battleground of a fruitlessly defended green space, is a stunted obelisk set on a carpet of stone flags. Its octagonal base serves as somewhere to sit for those who take advantage of the Duke of Wellington’s barbecue night, a stand for lager cans.’

‘ As we slogged south/east, sticking grimly to our line’, Sinclair is decidedly disappointed by London Fields because of its lack of graffiti; ‘Not a squiggle, not a curse; no conjuring symbols carved into the peeling bark of the still impressive avenue. Even the titular deities, a Cockney/Aztec pearly king and queen rendered in cement and multi-coloured tesserae, are undefaced.’

As we slogged south/east, sticking grimly to our line’, Sinclair is decidedly disappointed by London Fields because of its lack of graffiti; ‘Not a squiggle, not a curse; no conjuring symbols carved into the peeling bark of the still impressive avenue. Even the titular deities, a Cockney/Aztec pearly king and queen rendered in cement and multi-coloured tesserae, are undefaced.’

Next, we head to Victoria Park, ‘Going over, crossing into LibDem territory: Victoria Park. St Agnes gate and the green lung’. He doesn’t much like the statuary on the way to the Bonner Gate: ‘Twin white horrors, the Dogs of Alcibiades, raised on brick plinths. When they were blessedly removed, for months, my spirits surged – but, inevitably, this was no more than a truce. The frosty albinos are back, resprayed, restored (scrawny, loose fleshed, wolf-headed, genitally deprived) …

Next, we head to Victoria Park, ‘Going over, crossing into LibDem territory: Victoria Park. St Agnes gate and the green lung’. He doesn’t much like the statuary on the way to the Bonner Gate: ‘Twin white horrors, the Dogs of Alcibiades, raised on brick plinths. When they were blessedly removed, for months, my spirits surged – but, inevitably, this was no more than a truce. The frosty albinos are back, resprayed, restored (scrawny, loose fleshed, wolf-headed, genitally deprived) …

Next, we ‘exit through the grandiloquent boast of the Bonner Hill gates’, and head to somewhere Sinclair rather likes: ‘Meath Gardens is a favourite of mine, one of the extramural city’s most numinous (unvisited) locales.’ (it used to be Victoria Park Cemetery).

Then, ‘Under the railway bridge and follow the wall into Bancroft Rd’. The Bancroft Road Mile End Workhouse (now Mile End Hospital) is on the left down towards the end. This may well have been George Orwell’s destination when he set out from Limehouse Causeway. He describes waiting to get in on the first night:

‘At six, the gates swung open and we shuffled in. An official at the gate entered our names and other particulars in the register and took our bundles away from us. The woman was sent off to the workhouse, and we others into the spike. It was a gloomy, chilly, limewashed place, consisting only of a bathroom and dining-room and about a hundred narrow stone cells. The terrible Tramp Major met us at the door and herded us into the bathroom to be stripped and searched.’

We walk past Tower Hamlets’ Local History Library – a rather fine nineteenth-century building, with its ‘grand entrance hall’; then left along the Mile End Rd past the People’s Palace, now the University of London. ‘Panels in relief, executed by Eric Gill, depict Drama, Music, Fellowship, Dance, Sport.’ Then we head down to the canal again and walk south along the towpath to Limehouse, pausing at the beautiful St Anne’s Limehouse, a Hawksmoor church consecrated in 1730. Sinclair describes ‘in one of the alcoves, so well adapted to resting vagrants, the cheerful slogan: GOD BLESS YOU ALL’.

The church is also featured in Peter Ackroyd’s book ‘Hawksmoor’ (1985), a tale of Satanic practices and murder: ‘By day my House of Lime will catch and intangle all those who come near to it; by Night it will be one vast Mounde of Shaddowe and Mistinesse, the effect of many Ages before History.’

Surprise, surprise, Sinclair doesn’t like Canary Wharf, explaining that ‘we thin as we walk’. Things improve again in the ‘Island Gardens, fronting the river and Greenwich, where Maze Hill shimmers in rainlight. The relief: a return to language.’

Surprise, surprise, Sinclair doesn’t like Canary Wharf, explaining that ‘we thin as we walk’. Things improve again in the ‘Island Gardens, fronting the river and Greenwich, where Maze Hill shimmers in rainlight. The relief: a return to language.’

And he seems to be fascinated, as we are, by the Greenwich foot tunnel under the Thames, built in 1902 to allow workers living south of the Thames to reach their workplaces in the London docks.

‘The tile loop of the foot tunnel is visible on a giant TV screen in the lift’…’When it’s our turn to perform for the camera, to walk down the narrow bore of the tunnel, to contemplate the tons of brown water above our heads, we remember that, of all London, this is PD James’ worst nightmare (Original Sin). For that reason, if no other, we relish it.’

‘Pleasantly disorientated; the south side of the river is much more than a simple culture jump, it operates on an entirely different pulse.’ It does feel completely different, much more genteel and touristy.

We find the very site of the café that Sinclair went to for a late breakfast, The Terminus at 38 Greenwich Church Street, now called the Cutty Sark Café.

‘It’s coming straight down, no argument, bar-code blocks of it – driving us into the shelter of the nearest grease caff. No time to be picky, to choose somewhere rough enough to feel comfortable with my patronage…We steam in the window, knees rattling the formica; affecting the biosphere with our transported weather systems.’

And so our walk finishes. We hope you get better weather for yours than Iain Sinclair and his mate did! And not that it really matters, but it turns out ‘The University of Greenwich isn’t actually in Greenwich.’

OTHER STUFF

Read: An excerpt from George Orwell’s ‘Spike’ at https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/the-spike/

Take A Tour: Bethnal Green in So Many Words, http://charnowalks.co.uk/bgn-so-many-words/

Read: ‘A Journey Through Ruins’ (1991), The Last Days of London, by Patrick Wright, which starts in Dalston Lane

15th May 2022 at 11:15 pm

Very interesting. But given the calibre of the women writers connected with Stoke Newington it seems perhaps careless not even to have mentioned their existence… Mary Wollstonecraft is the obvious one. Beyond her, Anna Laetitia Barbauld is at least as interesting a figure as Tom Raworth, for instance, and many women writers of the late C18 & early C19 came to see her – the so-called Bluestockings, who included writers like aJoanna Baillie and the remarkable writer & actress Mary Robinson.

22nd May 2022 at 10:41 am

Katy, I’m so glad you read my piece.

I’m going to research the authors you mention, thanks for the suggestions.

Mary W. also gets a good mention in my Bournemouth walk.