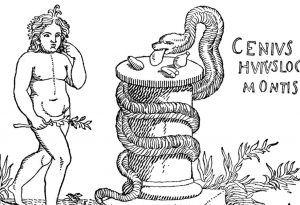

What is meant by ‘Genius Loci’, ‘spirit of a place’?

In classical Roman religion, a ‘genius loci’ was the protective spirit of a place. It was often depicted in religious iconography as a figure holding attributes such as a cornucopia, patera (libation bowl) or snake. Many Roman altars found throughout the Western Roman Empire were dedicated to a particular genius loci.

In classical Roman religion, a ‘genius loci’ was the protective spirit of a place. It was often depicted in religious iconography as a figure holding attributes such as a cornucopia, patera (libation bowl) or snake. Many Roman altars found throughout the Western Roman Empire were dedicated to a particular genius loci.

The phrase ‘genius loci’ has come to refer in this country to a location’s distinctive atmosphere, the ‘spirit of the place’.

Alexander Pope (1688-1744) was one of the first to use the phrase. He made the ‘genius loci’ an important principle in garden and landscape design as we see from the following lines from ‘Epistle IV to Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington’:

Consult the genius of the place in all;

That tells the waters to rise, or fall;

Or helps th’ ambitious hill the heav’ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the vale;

Calls in the country, catches opening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades,

Now breaks, or now directs, th’ intending lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

Pope’s verse laid the foundation for one of the most widely agreed principles of landscape architecture. This is the principle that landscape designs should always be adapted to the context in which they are located.

And since the eighteenth century, many novels and much poetry have taken this approach to the ‘genius of the place’, imbuing it with a special significance.

‘Whoso hurries unduly will never catch the genius loci of those regions…’ Norman Douglas

‘There is such a thing as the genius loci… and it is possible that certain districts actively modify the behaviour of people who live in them’. Peter Ackroyd

Soon after arriving at Dove Cottage, Wordsworth began writing a series of poems themed on the idea of a ‘sense of place’. It was an attempt to combine poetry-making with homemaking and to inscribe a genius loci on the landscape. In 1800 Wordsworth wrote an introduction to the series:

‘By Persons resident in the country and attached to rural objects, many places will be found unnamed or of unknown names, where little Incidents will have occurred, or feelings been experienced, which will have given to such places a private and peculiar interest. From a wish to give some sort of record to such Incidents or renew the gratification of such Feelings, Names have been given to Places by the Author and some of his Friends, and the following Poems written in consequence.’ The first of these places is Glow Worm Rock. The story of John’s Grove is told in ‘When, to the Attractions of the Busy World’, the sixth poem in the Naming of Places series.

Landscape is re-assuring, it changes only slowly, people and circumstances change but often the landscape remains a point of continuity. That is why it is so painful when it changes e.g. John Clare and the destruction that enclosure wreaks on the natural landscape, and Gerard Manley Hopkins mourning his ‘aspens dear’. It is often a very emotional moment when a tree is cut down for all of us when our landscape changes….think recently of the Sycamore Gap tree on Hadrian’s Wall that was brutally cut down.

What rural heritage do each of our writers come from, and how does that affect their work about nature and landscape?

Working-class: John Clare (farmer’s family), DH Lawrence (mining family). A very close reading of what they see around them in the countryside.

One step removed: Ronald Blythe (his father came from generations of East Anglian farmers), Ted Hughes (his brother was a gamekeeper), Thomas Hardy and Flora Thompson (their fathers were both stonemasons), Laurie Lee (rural village life). More of an observer feel, albeit very accurate observations.

In the landscape, but not directly connected to the land: Wordsworth. Despite his vivid landscape descriptions, he often seems very disconnected from the life of the Lake District people. A more distant observer.

‘Discovered the countryside’ converts: Daphne du Maurier, AA Milne, Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie, Beatrix Potter. The countryside very much represents an escape.

The naturalists: Gilbert White (‘The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne’), Richard Mabey, Nan Shepherd (‘The Living Mountain’), Robert Macfarlane. Forensic descriptions.

‘Townies’: Charles Dickens, Jane Austen. It’s really about the people, stupid.

‘Psychographers’: Debord, Iain Sinclair, Will Self etc. They describe what happens ‘when psychology meets geography’.

Travel writers: William Cobbett, Celia Fiennes, Daniel Defoe. Tend to be very matter-of-fact, determined to strip their descriptions of too much embellishment.

How do writers use landscape and setting in their work?

‘No City or landscape is truly rich unless it has been given the quality of myth by writer, painter or by association with great events.’ VS Naipaul

Writers use landscape in many different ways to express and inform their work:

- To add authenticity – this is a ‘real’ experience and brings the writing to life through its accuracy and insight e.g. the opening chapters of ‘Sons & Lovers’

- To offer a metaphor – the brooding moors in ‘Wuthering Heights’ are a metaphor for the character of Heathcliff

- To give a sense of permanence and continuity – people change, things change, but nature/landscape often remains the same. ‘Eternity flows in a mountain brook’. (Norman Nicholson)

- To imbue a passage with nostalgia – the landscape of one’s childhood, memories. ‘The Olde Vicarage’ Grantchester is a good example of this, written by Rupert Brooke in Germany when he was feeling homesick. Or ‘Cider with Rosie’.

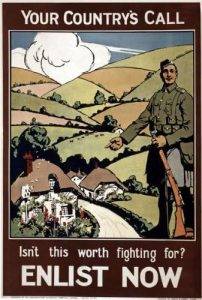

- And an extension of this, a source of patriotic pride and a reason to fight, nostalgia for homeland, especially during the First World War; epitomised by AE Houseman, and some of Flora Thompson’s poetry alluding to the loss of her brother:

‘Ah, very deep my Love must sleep,

‘Ah, very deep my Love must sleep,

On that far Flemish plain,

If he does not know that the heath-bells blow

On the Hampshire hills again!!

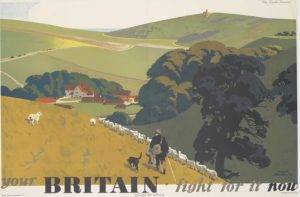

This patriotic link returned in the Second World War with a series of posters from the Ministry of Information entitled ‘Your Britain – Fight for it Now’.

As a ‘quarry of characters’ – this is how people are in a geographic setting e.g. Under Milkwood and James Joyce’s Ulysses. Joyce said that if Dublin was destroyed, it could be rebuilt using Ulysses as a guide.

- To be a reminder of unvarnished reality – contrasting with the contradictions and veneer of society. Often a representation of freedom and escape from society (the closing passage of DH Lawrence’s ‘Sons & Lovers’)

- As a source of spiritual enrichment – The Metaphysical Poets, Gerald Manley Hopkins, The Romantic Movement

- As a ‘religion’, for example vitalism and animism. Vitalism is based on the theory that the origin and phenomena of life are dependent on a force or principle distinct from purely chemical or physical forces. Animism is the belief in a supernatural power that organises and animates the material universe

- Thought-provoking – often the case with city walking – Charles Dickens and Virginia Woolf are stimulated by what they see around them

- A statement of ultra-realism – the ‘gritty’ psychographers, or WH Auden who hated the Romantic movement and liked walking by the gas works in Oxford as a way of reflecting how life really is

- As an agent of change – the changing seasons, the arrival of the railways in Thomas Hardy etc. (obviously not at the same time as 3!)

This sense of being part of a landscape, of ‘belonging’, is central to one’s identity and is explored time and time again in English literature. You probably know that feeling of ‘associating’ with a landscape, I still have it from my youth growing up in the shadow of the South Downs – I haven’t been back for ages, but I still feel that association, based on a visual appeal and a reading of topography, flora and fauna, a sense that I ‘get it’.

In what ways are different types of landscapes used to symbolise different things?

Landscape is a key symbolic tool in many literary works, and within that different landscapes often communicate different things:

Types of landscape

Mountains – peaks, aspirations, endeavour, wonderment, revelation, sublime moments (Wordsworth)

Meadows – well-being, fecundity – (Tess of the D’Urbervilles, the Valley of the Great Dairies

Heaths, moorlands – wild, untrammelled (Wuthering Heights, terurn of the native

Woods – two sets of thoughts:

Either: intimate and friendly – Robert Frost’s ‘The Sound of Trees’. The Ents in Tolkien.

Or: full of wild beasts and terror… fearful things, full of shadows and restricted vistas. Dante had the road to hell passing through a dark forest. In fairy tales, forests can be bad places

Streams – positivity, source, the story of life, continuity cf Nan Shepherd

Sea – eternity (Matthew Arnold)

Home vs. ‘other places’

Home (familiar, safe, dull) vs. ‘other places’ (adventurous, experimental, scary)

So many writers gain a sense of belonging from their childhood and are stuck in the dichotomy of home/security/love versus breaking out to experience the world. This is often the basis for a novel’s plot. All novels to some extent are about a journey from certainty to uncertainty, sometimes with a resolution back to certainty.

‘There is a magic in that little world, home; it is a mystic circle that surrounds comforts and virtues never known beyond its hallowed limits.’ Robert Southey

Home:

- Slad (Cider with Rosie)

- CS Lewis the Mourne Mountains

- Tolkien’s Birmingham

- Egdon Heath, in several of Hardy’s poems

- Simon Armitage’s Marsden poems

- Ted Hughes – Heptonstall

- Eastwood DH Lawrence

‘Other’ Places

- Selbourne (Bournemouth) in Jude the Obscure

- Top Withens in Wuthering Heights

- As I set out one Summer’s Morning, Laurie Lee

- The Lion, the Witch & The Wardrobe

Country vs. city

Country vs. city is also another often-used contrast, where the country typically represents values of naturalness, honesty and simplicity, whilst the city represents greed, breakdown of family relationships and a loss of innocence, but also adventure (Hardy, Lawrence etc.) Look out for Raymond Williams’ great book on the topic, ‘The Country and the City’ (1973).

Country vs. city is also another often-used contrast, where the country typically represents values of naturalness, honesty and simplicity, whilst the city represents greed, breakdown of family relationships and a loss of innocence, but also adventure (Hardy, Lawrence etc.) Look out for Raymond Williams’ great book on the topic, ‘The Country and the City’ (1973).

What exactly are we looking for as literary explorers? How does one really get that ah-ha moment?

The History of Literary Tourism

As Nicola Watson explains in her admirable book  ‘The Literary Tourist’, the readers’ desire to experience the haunts, graves, and houses of their heroes has a long history, with visits to Shakespeare’s birthplace getting underway in 1769. The business really took off during the nineteenth century with the deification of Sir Walter Scott and all his works and has continued apace since then.

‘The Literary Tourist’, the readers’ desire to experience the haunts, graves, and houses of their heroes has a long history, with visits to Shakespeare’s birthplace getting underway in 1769. The business really took off during the nineteenth century with the deification of Sir Walter Scott and all his works and has continued apace since then.

Literary geographies took off in the forty years from the 1880s to the 1920s, brought together in William Sharp’s Literary Geography (1904).

In the twentieth century, it became an important tool of the tourist industry in many regions, Haworth, Wessex, Lorna Doone Country, Fowey, Cookson country, the list goes on…

Gillian Tindall is a bit sniffy about this type of undertaking: ‘Yet such an excursion tends, at best, to be no more than a luxurious appendage to the books in question and, at worst, a distraction from them, imposing the distortions of reality on a creation that is both less and more than the ‘real place’ that inspired it.’

Or as another literary visitor commented: ‘When I visit Chawton I want to feel something, and while looking at exhibits in glass cases is interesting, I always hanker for something more. I want to breathe in some of the magic. I want the hairs on the back of my neck to stand up. I want to feel a shiver down my spine. I ask for spirit from a place that was once home to a great spirit.’

In this collection of walks, we try and capture a sense of place, and they are all experiences that at some level worked for me, although inevitably the mood of the moment (both mine and the landscape’s) can play capriciously with the quality of the ‘shiver down the spine’, sometimes captured in the most unlikely of moments, like the worn step in the door (now a window) in Hardy’s cottage. And what else is important? Well, definitely a sense that you have stumbled across the moment yourself somehow…

Hierarchy of ah-ha moments

This is bound to be very personal and subjective, but this is my hierarchy of ah-ha moments according to type, from the least inspiring to the most:

Graves – least – unless that is you are already very emotionally invested in that author.

But where a grave is located often gives a good clue as to where the ‘heart’/’emotional home’ of the writer lies…quite literally in Thomas Hardy’s case, who was buried in Westminster Abbey but requested that his heart be returned to Stinsford Church.

Daphne du Maurier’s ashes were scattered on the cliffs near to her beloved Menabilly, Beatrix Potter’s above her home in Near Sawrey.

Birthplaces These can often be visited (probably in the case of at least half the writers we cover), but often disappoint as they are now part of a tourist/visitor industry. John Keats describes this as ‘the flummery of a birthplace’. John Clare’s Cottage, Thomas Hardy’s Cottage and DH Lawrence’s first home are a reminder of what cramped spaces many lived in.

Homes – Abbotsford, Haworth Vicarage, High Top, Greenway House, Chawton Cottage, Rodmell, Menabilly, Newstead Abbey, Dove Cottage, Gough Square etc. all have huge significance attached to them and are generally very worthwhile to visit.

Writing Space – Dylan Thomas, George Bernard Shaw, Virginia Woolf, Roald Dahl. ‘Wring spaces seem to be a very Victorian and earlier part of the twentieth-century thing, where people would have set patterns of work that enabled them to escape the pressures of family life (often to the annoyance of the spouse). As P.D. James points out, for a writer immersed in different fictional worlds it would have been difficult being jolted back to reality by such frequent interruptions:

‘Every writer of genius needs, for her physical and mental health as well as for her art, a small inviolate cell of mental privacy, and it is precisely this emotional privacy that, for much of her life, Jane Austen was denied.’ (until she got to Chawton Cottage)

Real places featured in the writing – Menabilly (Daphne du Maurier), The Talbot Inn (Chaucer), Stinsford Church (Thomas Hardy), Greenway House (Agatha Christie), Slad (Laurie Lee). This starts to get very interesting, and for me at least threw up several ‘ah-ha’ moments.

Natural features mentioned in the writing – for me, these were the most exciting ‘ah-ha’ moments – discovering Gerard Manley Hopkins’ actual cliff where he saw the Windhover or the mound of Egdon Heath where the figures dance at night in front of the fire, or the exact spot where the Six Young Men had their picture taken (Ted Hughes) or Holford Beck in the Quantocks (Coleridge inspiration) or the bench in the Oxford Botanic Garden where Lyra and Will sat in His Dark Materials, or the smoke rising from an ancient cottage along the Wye…and there were many more. The absolute magic moments of literary wanderings. You will experience some just the way I did, and others that I will have completely missed…

What do the writers themselves think about their use of landscape and specific places?

Some writers are quite dismissive of course that we should be looking around for visual clues:

JK Rowling, for one, is very circumspect about her inspirations: ‘If you define the birthplace of Harry Potter as the moment when I had the initial idea, then it was a Manchester-London train,’ she wrote. ‘But I’m perennially amused by the idea that Hogwarts was directly inspired by beautiful places I saw or visited, because it’s so far from the truth.’

Even one so imbued in landscape such as Thomas Hardy wrote, in the 1912 Preface to his novel The Woodlanders:

‘I have been honoured by so many inquiries for the true name and exact locality of the hamlet ‘Little Hintock’, in which the greater part of the action of this story goes on, that I may as well confess here once for all that I do not know myself where that hamlet is more precisely than as explained above and in the pages of the narrative. To oblige readers I once spent several hours on a bicycle with a friend in a serious attempt to discover the real spot; but the search ended in failure; though tourists assure me positively that they have found it without trouble, and that it answers in every particular to the description given in this volume.’

Virginia Woolf wrote in her first published article (1904): ‘I do not know whether pilgrimages to the shrines of famous men ought not to be condemned as sentimental journeys. It is better to read Carlyle in your own study chair than to visit the sound-proof room and pore over the manuscripts at Chelsea.

The curiosity is only legitimate when the house of a great writer or the country in which it is set adds something to our understanding of his books. This justification you have for a pilgrimage to the home and country of Charlotte Brontë and her sisters.’

Writers do not face the same constraints as architects as they attempt to create or re-create a ‘genius loci’, so they can conjure up the actual experience of one place, add spice from their experience of another and then add a piece of fictional setting if they so choose… that’s the joy of creative writing!

The publicity & tourist imperative

Often locations are pushed by a tourist office, or even by the author’s publisher themselves trying to drum up enthusiasm for an author; ‘Cookson Country’ etc. Or even by the authors themselves, as was the case with Beatrix Potter and Laurie Lee.

Of course, commercial priorities often unintentionally ruin the spirit of a place. How can using these names be in any way uplifting?! These are some of the places I have seen in my travels:

- The Hungry Hobbit, Birmingham

- Shakespeare in Love Wedding Boutique, Shakespeare’s Sister soap, Shakespaw Cat Café, Stratford upon Avon.

- The Defoe Arms, east London (true to form, it went bust…)

- Virginia Woolf Burger Bar & Grill (Hotel Russell) and Dalloway Terrace (at The Bloomsbury)

- Bronte Original Unique Yorkshire Liqueur, Heathcliff Café, Villette teashop

- Roget by Malvern Hills Brewery, an English Mild Ale.

- Unicorn Pub (Malvern)

- Ancient Mariner Pub, Nether Stowey

And the ‘most claimed’ literary object of all goes to the gas lamp in Narnia, which is located just about everywhere that CS Lewis ever went that has a gas lamp, so Oxford, Malvern and Belfast to name just a few…

And the ‘most claimed’ literary object of all goes to the gas lamp in Narnia, which is located just about everywhere that CS Lewis ever went that has a gas lamp, so Oxford, Malvern and Belfast to name just a few…

Happy wandering!! Tell me how you get on.

Leave a Reply