‘Upon entering the town of Stratford, a feeling, I trust, something more elevated than of mere curiosity, naturally depicts the steps of every admirer of our divine Poet towards that spot which gave birth to the most extraordinary genius this or any other country has ever produced…’ Samuel Ireland, 1795

KEY DATA

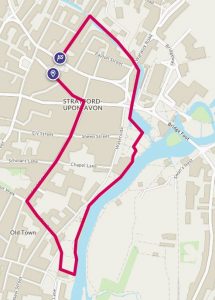

- Terrain: Pavements throughout

- Starting point: Shakespeare Birthplace, Henley St, CV37 6QW

- Distance: 2.5 km (1. 6 miles)

- Walking time: 38 mins

- Map: The route can be found online at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10812016/StratforduponAvon-Warwickshire-William-Shakespeare

- Facilities: All

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, THE ‘BARD OF AVON’ (1564-1616)

The cult of Shakespeare, or ‘Bardolatry’ as it is often termed, had its origins in the mid-eighteenth century when Samuel Johnson wrote:

‘He had looked with great attention on the scenes of nature; but his chief skill was in human actions, passions, and habits…his works may be considered as a map of life, a faithful miniature of human transactions’.

Stratford-upon-Avon’s transition from Midlands market town to ‘Birthplace of the Bard’ soon followed when, In 1769, the famous actor and theatre manager David Garrick staged a massive Jubilee in Stratford to celebrate the birth of William Shakespeare, culminating in the unveiling of a statue of Shakespeare in front of the Town Hall at which he read out a poem ending with the words ’tis he, ’tis he, / The God of our idolatry’.

The script of the Jubilee established Stratford and the surrounding Warwickshire countryside as the natural location of the Shakespeare cult, partly by general invocation of the bard as a local – ‘The Will of all Wills was a Warwickshire Will’, as the hit-song of the festival chorused.

The final step was to codify the physical links, which Samuel Ireland did with his guidebook ‘Picturesque Views on the Upper, or Warwickshire Avon’ (1795). In it, Ireland models for his reader a must-do itinerary, a useful guide to appropriate sentiments and suitable activities.

This set the tourist industry going and fired the sort of enthusiasm that one reader expressed in this way: ‘STRATFORD! All hail to thee! When I tread thy hallowed walks; when I pass over the same mould that has been pressed by the feet of SHAKESPEARE, I feel inclined to kiss the earth itself.’

So, Shakespeare’s birthplace as we see it today is the product of more than two centuries of creative conjecture and an ever-growing tourist trade. The actual facts are that Shakespeare was born here in 1654, his father was a leather glove maker and an alderman of the town, he married Anne Hathaway when he was 18, had three children and died here. As Bill Bryson put it in his book on Shakespeare ‘we know almost nothing about the most famous writer in the English language’ beyond that.

But a study of his ‘idiolect’ – the speech habits peculiar to a particular person – is definitely indicative of a country upbringing. His plays abound with references to rural characters, country customs, wildflowers, animals and birds that could only really be that of someone from this part of the country. And, given his father’s profession, it is not surprising that he used many leather tanning terms.

OUR WALK

Our first stop is Shakespeare’s Birthplace, where William and his sisters were born and brought up.

We soon learn that we are just the latest in a long line of ’The Birthplace of the Bard’ pilgrims. Two early U.S presidents, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson visited in 1786; the first visitors’ book was created in 1812; and in 1818, Mary Hornby gathered together a collection of ‘Extemporary verses, written at the ‘Birthplace of Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon by People of Genius’.

We peer at the famous preserved window laden with historic graffiti. What had begun life as an 1800s-built window now stands as a monument not only to Shakespeare but also to the pilgrimage of the many, both the famous (Sir Walter Scott, Ellen Terry, Thomas Carlyle and Isaac Watts) and the ordinary (‘Little Jack Stubbs’ is one of the inscriptions) to the place of his birth. There was also a tradition of taking souvenirs, bits of furniture, and reliquaries in the same way as a traditional pilgrimage.

To visit the Birthplace nowadays is thus to recapitulate two and a half centuries of previous pilgrimage. It would have been still more so if they hadn’t whitewashed away all the graffiti on the walls in 1947 after a guidebook stated that ‘the rooms should be as Shakespeare saw it, not with its walls scrawled on by every loon and lout who comes this way’. Sir Walter Scott, stand in the naughty corner!

One of the famous visitors who signed the visitors’ book in 1844 was the legendary American showman, PT Barnum. Naturally enough he recognised the potential pulling power of Shakespeare. He wrote:

‘While in Europe I was constantly on the look-out for novelties… I obtained verbally through a friend the refusal of the house in which Shakespeare was born, designing to remove it in sections to my Museum in New York; but the project leaked out, British pride was touched, and several …. English gentlemen interfered and purchased the premises for a Shakespeare Association…’(one of the gentlemen incidentally was Charles Dickens.)

Outside the Birthplace is a recent statue of Shakespeare by artist James Butler, ideal for the Instagram generation of tourists. This statue offers a kind of easy familiarity that isn’t possible with most images of Shakespeare to be found in the town.

Outside the Birthplace is a recent statue of Shakespeare by artist James Butler, ideal for the Instagram generation of tourists. This statue offers a kind of easy familiarity that isn’t possible with most images of Shakespeare to be found in the town.

We head south through the town. Nash’s House was the home of Thomas Nash who married Shakespeare’s granddaughter. It dates back mainly to the sixteenth century, with the half-timbered front being a reconstruction of the original, which was replaced by a brick front in the 1700s. It is now the home of the Stratford Local History Museum.

In 1597, at the age of 33 and having met with much success in London, Shakespeare bought New Place, a grand family home. He died there in 1616. It was the largest house in the borough, and the only one with a courtyard – a significant purchase for the 33-year-old Shakespeare in 1597. Though the house no longer exists, the site is owned by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, which maintains it as a specially designed garden, intended to replicate the flowers, herbs and spices that were typically grown in the Elizabethan period.

The story behind the house is perhaps the first recorded example of locals getting fed up with the tourists and taking drastic action. There was a mulberry tree in the garden supposedly planted by the playwright himself, which was a popular point of pilgrimage, but meant visitors regularly traipsed through the garden. In a fit of pique the then owner, the Reverend Francis Gastrell, chopped the tree down. The house soon followed as a way of avoiding taxes which it turned out he hadn’t paid.

The Town Hall on the left stands where the first market hall was built in 1643. It was damaged in the Civil War and rebuilt in 1767. David Garrick staged much of the 1769 Festival here.

The Old Bank opposite was built in 1883. We admire the mosaic above the front door depicting the Merchant of Venice (quite fitting for a bank), and the frieze around the edge that depicts scenes from many of Shakespeare’s plays.

Our visit to Shakespeare’s Schoolroom & Guildhall brings to life Shakespeare’s time as a schoolboy, from about 1571 to 1578. Pupils sat on forms – long boxes – with lids that could be raised to hold their satchels and anything else that had to be put away. This is where they would be instructed to go to the top or the bottom of the form. The Master would address the pupils in Latin, and they would reply in Latin. Entering the room, we were greeted by the Master, sitting at his raised Tudor desk, dressed in period costume. He tells us to sit down and be quiet.

Our visit to Shakespeare’s Schoolroom & Guildhall brings to life Shakespeare’s time as a schoolboy, from about 1571 to 1578. Pupils sat on forms – long boxes – with lids that could be raised to hold their satchels and anything else that had to be put away. This is where they would be instructed to go to the top or the bottom of the form. The Master would address the pupils in Latin, and they would reply in Latin. Entering the room, we were greeted by the Master, sitting at his raised Tudor desk, dressed in period costume. He tells us to sit down and be quiet.

Hall’s Croft. Shakespeare’s daughter Suzanna and her husband Dr John Hall lived here from 1613-1616, moving to New Place after her father’s death. It contains an exhibition of the peculiar medical practices of Shakespeare’s time. We wander into the tranquil walled garden to discover fragrant, medicinal herbs.

William Shakespeare was baptised in Holy Trinity Church on 26 April 1564 and was buried here on 25 April 1616, both events recorded in the Elizabethan register.

The words over his grave in the chancel are said to be his own:

‘Good friend for Iusus sake forbeare,

To digg the dust enclosed heare.

Bleste be ye man yt spares thes stones,

And curst be he yt moves my bones.’

Shakespeare would have come to Holy Trinity every week when he was in the town, i.e. all through his childhood and on his return to live at New Place. His wife Anne Hathaway is buried next to him along with his eldest daughter Susanna.

The Royal Shakespeare Theatre is now coming up on our right as we head back along the river. It was first opened in 1932 and substantially re-developed in 2010. The theatre is now a one-room theatre, which allows the actors and the audience to share the same space, as they did when Shakespeare’s plays were first produced.

The Royal Shakespeare Theatre is now coming up on our right as we head back along the river. It was first opened in 1932 and substantially re-developed in 2010. The theatre is now a one-room theatre, which allows the actors and the audience to share the same space, as they did when Shakespeare’s plays were first produced.

The River Avon has always been of central importance to the town of Stratford and the area surrounding it. In Shakespeare’s day, it was an important artery for trade and a source of waterpower.

Garrick of course felt that Shakespeare composed his work alongside the river, inspired by nature, the ultimate ‘genius loci’:

‘Thou soft flowing Avon, by the silver stream,

Of things more than mortal thy Shakespeare would dream.

The fairies by moonlight dance round the green bed

For hallow’d the turf is which pillow’d his head.’

We pass through Bancroft Gardens and spot the Gower Memorial. The memorial is a statue of Sakespear (you weren’t expecting someone else were you?!), with four characters from his plays. So you have Lady Macbeth for tragedy; Hamlet for philosophy; Falstaff for comedy and Prince Hal for history. Behind each character, on the main statue, is a bronze mask and flowers to represent the character.

We pass through Bancroft Gardens and spot the Gower Memorial. The memorial is a statue of Sakespear (you weren’t expecting someone else were you?!), with four characters from his plays. So you have Lady Macbeth for tragedy; Hamlet for philosophy; Falstaff for comedy and Prince Hal for history. Behind each character, on the main statue, is a bronze mask and flowers to represent the character.

We finish up at the bridge and watch the eddying waters, reminded of Shakespeare’s powers of observation:

‘Glory is like a circle in the water,

Which never ceaseth to enlarge itself,

Till by broad spreading it disperses to naught.’ (Henry VI, Part I)

Perhaps a good analogy for the ‘cult of Shakespeare’ – ever-growing and yet so chimeric too.

OTHER STUFF

Visit: the village of Shottery, where Anne Hathaway’s Cottage is located. Download a guide at https://natpacker.com/shakespeare-birthplace-trust-adventure/. It’s about a 30-minute walk each way. Naturally enough, you will see a four-poster bed that just might be that famous ‘second-best’ bed.

Take: A Shakespeare-guided tour, of which there are many, including www.stratfordtownwalk.co.uk

Leave a Reply