‘All my beginnings were hatched into this very compact series of narrow, brief valleys, which are like seed pods.’

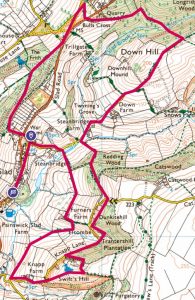

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Hills and fields

- Starting point: The War Memorial, Slad (GL6 7QD)

- Distance: 8.3 km (5.2 miles)

- Walking time: 2 hrs 53 mins

- OS Map: OS Explorer 80. The map can also be found at https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/10704685/Slad-Gloucestershire-Laurie-Lee

- Facilities: Pub

LAURIE LEE (1914-1997)

Born in nearby Stroud, Laurie Lee moved with his family to the village of Slad when he was just three, and next walked out early one summer’s morning when he was nineteen, with a hazel stick in his hand and a violin wrapped in a blanket under his arm. ‘Cider with Rosie’ and’ As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning’ made him famous, one a chronicle of belonging, the other a chronicle of leaving.

‘Cider with Rosie’ is set in a rural world far removed from our own, where life revolved around agriculture and the pattern of existence had gone on largely unchanged for hundreds of years. The book is a celebration of childhood and is full of charm and beauty, but also the harsh, impoverished realities of village life before the welfare state. In his memoir, Laurie Lee recalls the Slad of his 1920s childhood as ‘a deep-running cave still linked to its antic past’, its shadows ‘cluttered by spirits and by laws still vaguely ancestral’.

Because of its setting in a valley, it is easy to see how old folk half-believed that the world ended beyond their valley. ‘Living in our valley was like broad beans in a pod,’ Laurie Lee wrote. ‘All my beginnings were hatched into this very compact series of narrow, brief valleys, which are like seed pods.’ Even today when we visit, we still find a village cut off by the wooded crests of its enfolding hills, the trees oozing ‘over the lips of the hills like layers of thick green lava’.

Laurie Lee is perhaps unmatched in creating a sense of place, evoking such startlingly vivid images of people and landscapes. it is his ability to express so lucidly and eloquently what he observes that makes him such a great nature writer. I like his description of his first morning when he came back to Slad:

‘As I was waking, I heard a blackbird singing. I had forgotten I had left the village and I thought, he sounds like a Gloucestershire blackbird; he sounds like a Slad blackbird. And then, when I was fully awake, I realized it was a Slad blackbird. I had not heard it for twenty years, but it was instantly recognisable because they mimic their fathers and mothers.’

In the 1960s, Laurie Lee and his wife bought Rose Cottage in Slad and returned permanently.

Laurie Lee of course was a great walker: ‘The next day, getting back on to the London road, I forgot everything but the way ahead. I walked steadily, effortlessly, hour after hour in a kind of swinging, weightless realm. I was at that age which feels neither strain nor friction, when the body burns magic fuels, so that it seems to glide in warm air, about a foot off the ground, smoothly obeying its intuitions. Even exhaustion, when it came, had a voluptuous quality, and sleep was caressive and deep, like oil.’

OUR WALK

Much of our route follows the Laurie Lee Wildlife Way, which is well-marked throughout. The walk passes a number of posts, each inscribed with a Laurie Lee poem.

We set out from the War Memorial, the site of a murder in ‘Cider with Rosie’ that was never solved. A ‘village boy made good’ returned from New Zealand one winter’s evening and made the mistake of bragging about his wealth in the public bar of the Woolpack. He went on to taunt the local young men for a crowd of stay-at-home peasants. When he left the pub in a blinding snowstorm the young men were waiting for him by the War Memorial. They beat and kicked him senseless, threw him over a wall and left him to freeze to death in the snow. This episode is a reminder that ‘Cider with Rosie’ has as many dark sides to it as pastoral idyllic ones.

We walk up into Frith Wood, Brith Wood in ‘Cider with Rosie’. This was where Lizzie Berkley took no nonsense from Laurie’s gang who attempted to attack her and went into battle whirling her bag of crayons.

Coming out of the woods we reach Bulls Cross, a notorious crossroads haunted by phantom coaches, demonic goats and the victims of the gallows that stood here. Note the worn mounting block on the verge. Lee depicts Bulls Cross as a ‘no-man’s crossing… a ‘ragged wildness of wind-bent turves where travellers would meet in suspicion, or lie in wait to do violence on each other, to rob or rape or murder.’ Lee states that a hangman’s gibbet once hung here.

A couple of hundred metres along the road to Sheepscombe was the house that old Emmanuel Twinning shared with his skewbald horse. ‘Emmanuel Twinning, on the other hand, was gentle and very old, and made his own suits out of hospital blankets, and lived nearby with a horse. Emmanuel and the skewbald had much in common, including the use of the kitchen, and one saw their grey heads, almost any evening, poking together out of the window.’

We then take the footpath into Longridge Wood. On our right, as we descend towards Slad Brook, is Deadcombe Bottom, where the remains of the hangman’s house are hidden. This unfortunate man had executed his own son by mistake one dark night on the nearby Bulls Cross gallows. On realising the identity of his victim, the hangman had gone straight home and hanged himself from a hook behind the door. Laurie and his brothers discovered the ruins of the hangman’s house one day and often returned to play here, swinging from the hook behind the door.

We leave the Laurie Lee Way for a while on coming out of the wood and head southwest along a well-defined track, passing Down Farm on our left and then Steanbridge Farm by Slad Brook. Just up the track by the brook is Sixpence Bottom, past the tangle of trees in the valley bottom, where Laurie’s friend Sixpence Robinson lived – ‘the place past the sheepwash, the hide-out unspoiled by authority, where drowned pigeons flew and cripples ran free; where it was summer, in some ways, always.’ This was the spot where the village kids loved to head whenever they had free time, to dam the stream and muck around.

We re-join the Laurie Lee Way again and, just beyond Elcombe, the path leaves the road and follows a route through the steep slopes of the Laurie Lee Wood Nature Reserve. We sit where Laurie Lee must have sat when he described this view: ‘I’m sitting at the foot of Swift’s Hill. It seems to command the whole of the valley from Stroud up to Bulls Cross. Swift’s Hill just sits here like a great ancestral hump.’

On our way back to the village, we pass Furners Farm, the old cider farm described in Cider with Rosie, now a B&B and still offering a cider homebrew.

And the last field on the left, before we get back to the brook, is the famous field where Laurie and Rosie spend an amorous afternoon under the hay wagon, exchanging ‘cidrous kisses’ having had some of that local brew.

They had of course done a bit of work beforehand; ‘We carried cut hay from the heart of the rick, packed tight as tobacco flake, with grass and wildflowers juicily fossilized within – a whole summer embalmed in our arms.’

The village pond, just on our right, is where ‘almost everything happened in terms of games, village gossip, childish errors.’ In winter the pond was the scene of skating and sliding expeditions for the whole neighbourhood, and Laurie and his friends would join in until they had played themselves beyond exhaustion far into the night. ‘It was the centre of all our juvenile recreations, from winter skating to summer bathing.’

And, of course, Fred Bates the milkman discovered the naked body of poor crazed Miss Flynn floating among the lily weeds of the pond early one morning and gained himself a day’s fame in every house in Slad.

We stroll back into the village, past Steanbridge House on our left, where Squire Jones, the owner of the only car in Slad, lived, ‘white-whiskered, gaitered, booted and bonneted, ancient-tongued last of their world, who thee’d and thou’d both man and beast, called young girls ‘damsels’, young boys ‘squires’, old men ‘masters’.’ Young Laurie, uncomfortably dressed up as John Bull, was given a prize by the squire on the lawn here on Peace Day in 1919.

Entering the village

Just before we reach the main village road, we see Laurie Lee’s old home, Bank Cottages (now called Rosebank Cottage) down on our left, crouched snugly in its neatly hedged garden, a sturdy seventeenth-century building with a dark-grey roof blotched with lichen and moss, ‘its walls so thick that they kept a damp chill inside them whatever the weather’.

Just before we reach the main village road, we see Laurie Lee’s old home, Bank Cottages (now called Rosebank Cottage) down on our left, crouched snugly in its neatly hedged garden, a sturdy seventeenth-century building with a dark-grey roof blotched with lichen and moss, ‘its walls so thick that they kept a damp chill inside them whatever the weather’.

The Lees lived in the downstroke of the T and the top-stroke was divided between two ancient rivals, wine-brewing Granny Wallon – ‘Er-Down-Under’ – and snuff-taking Granny Trill – ‘Er-Up-Atop’. The grannies hated each other. Dressed alike in black muslin dresses, candlewick shawls and tall poke bonnets with trailing ribbons, they never spoke but communicated ‘by means of boots and brooms – jumping on floors and knocking on ceilings’.

Owing to its location so close to Slad Brook, the cottage is in the path of the floods that flow into the valley, and Laurie and his family had to go outside to clear the storm drain every time there was a heavy downpour, though even this sometimes failed to stop the sludge despoiling their kitchen. I guess the name of the valley of the valley is a clue, coming from the Saxon ‘Slaed’, which means ‘damp valley’.

The village school, according to Laurie, ‘provided all the instruction we were likely to ask for. It was a small stone barn divided by a wooden partition into two rooms – The Infants and The Big Ones. Every child in the valley crowding there, remained till he was fourteen years old, then was presented to the working field or factory, with nothing in his head more burdensome than a few mnemonics, a jumbled list of wars, and a dreamy image of the world’s geography…country schooling was little more than a cane-whacking interlude in which boys picked up facts like bruises and the girls scarcely counted at all …’

The Woolpack became Laurie’s local when he moved back to the village. It used to be, as the name suggests, a place where the packhorses from the hills, bringing the wool down to the Stroud mills, stopped for refreshment. It’s got great character, as we discover. With photographs and paintings of Laurie and a good selection of his books scattered around the bars like confetti, the pub has become almost a shrine to Slad’s most famous son.

The Woolpack became Laurie’s local when he moved back to the village. It used to be, as the name suggests, a place where the packhorses from the hills, bringing the wool down to the Stroud mills, stopped for refreshment. It’s got great character, as we discover. With photographs and paintings of Laurie and a good selection of his books scattered around the bars like confetti, the pub has become almost a shrine to Slad’s most famous son.

Finally, we head up towards the church and pass Laurie’s grave. As he had reflected some years before: ‘I’ve found a place halfway up the churchyard, near enough to the church to be aware of, in a spiritual sense, matins on Sunday morning, but also to be within reach of, in a temporal way, orgies on Saturday nights in The Woolpack. And alternating between the temporal and the spiritual is the way I wish to spend what eternity is left to me.’

Inside the church, where Laurie had been a member of the choir, we take a moment to gaze at the window devoted to his life. It was funded by Laurie’s family and a public appeal. The beautiful stained-glass panels include a map of Spain, a violin and his distinctive signature.

Passing back down the steps we look once again at his gravestone and the valley beyond. The inscription reads ‘He lies in the valley he loved’ – and now we are a little in love with it too.

OTHER STUFF

- Watch: ‘Cider with Rosie’ (1998)

- Read: ‘Laurie Lee, Down in the Valley, A Writer’s Landscape’, edited by David Parker (2019)

- Watch: ‘Laurie Lee’s Gloucestershire – A Writer’s Landscape’, which was transmitted by HTV West in August 1994

- Stay at: furnersfarm.co.uk, the farm where the seductive brew was created.

Leave a Reply