‘The loveliest spot that man have ever found’

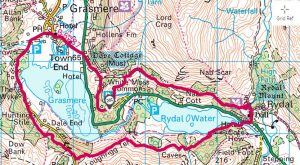

KEY DATA

- Terrain: ups and downs, and uneven surfaces around the lake

- Starting point: Stock Lane car park, Grasmere (LA22 9SJ)

- Distance: 10.2 km (6.4 miles)

- Walking time: 3h 7 min

- OS Map: Outdoor Leisure Map 7. The route can be found online at https://osmaps.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/route/8851334/Grasmere

- Facilities: Grasmere (toilets in the car park) and Rydal

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH (1770-1850)

Perhaps more than any other major English poet, Wordsworth was a poet of place. The experiences out of which he created his finest poetry he called ‘spots of time’, particular topographical places where natural or human pleasure or pain has occurred, and they are invested with the events that have occurred there. For more than fifty years his main ‘spot’ of land was Grasmere and Rydal Water, and this is where our walk is centred today.

Wordsworth first set up home at Dove Cottage in Grasmere in 1799 with his sister Dorothy, and over the next decade wrote most of his best-known verses there. William and Dorothy took particular pleasure in their wild-looking garden, which Wordsworth called their ‘little nook of mountain-ground’. Settling at Grasmere after years of the peripatetic was a very important transition in Wordsworth’s life, and he was never to leave the area again.

The siblings were soon joined by Wordsworth’s new wife, Mary, and the first three of their children were born there. It was a very busy house, with numerous visitors including Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas De Quincey. It must have been a very tight squash and, when finances allowed, they moved to the larger and grander Rydal Mount in 1813 and remained there until Wordsworth’s death in 1850 at the age of 80.

Dorothy Wordsworth (1771-1855)

Wordsworth’s much-loved sister Dorothy was his greatest support in these early years, his walking companion and the transcriber of his poems. She was vital to his well-being and creative output.

Her famous Grasmere Journals, a day-to-day account of their life between 1800 and 1803, written ‘to give Wm Pleasure by it’, provided recollections, ideas and even adjectives and verbs used in his poems. ‘She gave me eyes, she gave me ears’, Wordsworth declared. Dorothy observed the Lake District landscape in all seasons, all weathers and at all times of day and night. Her sensitivity to nature was also recognised by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge: ‘Her eye watchful in minutest observation of nature – and her taste a perfect electro-meter – it bends, protrudes, and draws in, at subtlest beauties and most recondite faults.’

Dorothy’s words are unvarnished and unadorned with classic references or strong opinions unlike her brother, and often the more authentic and poignant for that.

Wordsworth’s method of composition – composing by walking…

For Wordsworth walking and writing poetry were indivisible.

Thomas De Quincey famously remarked in Literary and Lake Reminiscences: ‘with these identical legs Wordsworth must have traversed a distance of 175,000 – 180,000 English miles…to which…he was indebted for a life of unclouded happiness, and we for what is most excellent in his writings.’

He was also a very fast walker, walking up to four hours per hour, and walking long distances at one time.

Wordsworth very much subscribed to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s beliefs about walking: ‘I meditate only when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think; my mind only works with my legs’.

He almost always composed his poems in the open air, so much so that one of his servants at Rydal Mount, on being asked permission to see his master’s study, replied ‘His study is out of doors’. He became famous for ‘bumming and booing’ around his garden, in other words composing his poetry by mumbling or murmuring in motion, composing the rhythm by the pace of his walking.

This is an eye-witness account of him on the grass walk at Rydal Mount: ‘Mr Wordsworth went bumming and booing about, and she, Miss Dorothy, kept close behint him, and she picked up the bits as he let ’em fall, and tak ’em down, and put ’em on paper for him.’

Dorothy’s Journal describes how: ‘Though the length of his walk is maybe sometimes a quarter or half a mile, he is as fast bound within the chosen limits as if by prison walls. He generally composes his verses out of doors, and while he is so engaged he seldom knows how the time slips away, or hardly whether it is rain or fair.’

THE WALK

The route of this walk is rather fittingly based upon an extract from Dorothy Wordsworth’s diary:

‘We walked round the two lakes. Grasmere was very soft, and Rydale was extremely beautiful from the western side. Nab Scar was just topped by a cloud which, cutting it off as high as it could be cut off, made the mountain look uncommonly lofty.’ Our plan today is to do exactly the same.

Dove Cottage

The delightful steep garden and orchard out the back were created by William and Dorothy with help from their friends. Many of his poems were written in and some even about the garden and orchard, in fact in the very spot we are sitting at now:

‘Beneath these fruit-tree boughs that shed

Their snow-white blossoms on my head,

With brightest sunshine round me spread

Of spring’s unclouded weather,

In this sequestered nook how sweet

To sit upon my orchard-seat!

And birds and flowers once more to greet,

My last year’s friends together.’

‘The Green Linnet’

We head slightly up the old turnpike road from the cottage to ‘John’s Grove’ (Lady Wood), a favourite spot of Wordsworth’s seafaring brother John, described by William as a ‘silent poet…’, ‘pacing to and fro’ the Vessel’s deck/In some far region’; sadly John was lost at sea in 1805.

In ‘When first I Journey’d Hither’, a tribute to his brother, Wordsworth writes of the joy of finding a path carved into the earth by him in John’s Grove:

‘With a sense

Of lively joy did I behold this path

Beneath the fir-trees, for at once I knew

That by my Brother’s steps it had been trac’d.

My thoughts were pleas’d within me to perceive

That hither he had brought a finer eye,

A heart more wakeful: that more loth to part

From place so lovely he had worn the track,

Out of his own deep paths!’

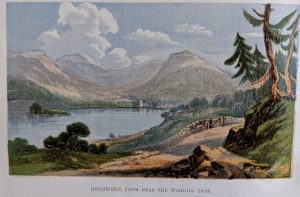

Just after coming out of John’s Grove, we cut back a few metres along the road and lean on the Wishing Gate (‘Sara’s Gate’) to enjoy the fabulous view over Grasmere Lake to Silver Howe. Wordsworth wrote the poem ‘To the Wishing Gate’ about it, and in its preface, he wrote: ‘In the Vale of Grasmere, by the side of the old highway leading to Ambleside, is a gate, which, time out of mind, has been called the Wishing Gate, from a belief that wishes formed or indulged there have a favourable issue.’

The Wordsworths liked to call it ‘Sara’s Gate’ because it was a favourite spot of Sara Hutchinson, Mary’s sister. Dorothy wrote: ‘I was much affected when I stood upon the second bar of Sara’s Gate. The lake was perfectly still, the sun shone on Hill and vale, the distant Birch trees looked like large golden Flowers – nothing else in colour was distinct and separate but all the beautiful colours seemed to be melted into one another, and joined together in one mass so that there were no differences though an endless variety when one tried to find out.’ The Diaries

Although the gate is not the original, the stone gateposts almost certainly are; and the original latch was preserved, and you can see it back down the hill in the museum.

Climbing up the slope alongside the quarry, we come to the bridleway to Rydal. This path was a coffin or corpse route, used to carry bodies from parishes that had no burial grounds to those that did. We notice a number of large flat stones, known as ‘resting stones’, used to rest the coffin on, as we walk along.

On the lake edge by the now busy road is Nab Cottage, once variously home to Thomas de Quincey and Hartley Coleridge, the son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Now we pass under Nab Scar, possibly the very spot of the first-ever ‘where shall we have our picnic?’ dilemma. As Dorothy wrote: ‘We determined to go under Nab Scar. Thither we went. The sun shone and we were lazy. Coleridge pitched upon several places to sit down upon, but we could not be all of one mind respecting sun and shade, so we pushed on to the foot of the scar. It was very grand when we looked up, very stony, here and there a budding tree…’

Wordsworth was fascinated by this stretch of path and walked it many times. He dramatised the rocky terrain in his poem ‘The Oak and the Broom’. This is the oak speaking:

‘Down from yon Cliff a fragment broke,

It came, you know, with fire and smoke

And hither did it bend its way.

This pond’rous block was caught by me,

And o’er your head, as you may see,

‘Tis hanging to this day.’

We look up slightly anxiously from our path and see that the oaks still seem to be holding back various rocks.

Tree-covered Heron Island, just alongside us now, was a favourite picnic spot for William and Dorothy, and they would often row out to it.: ‘The waves round about the little Island seemed like a dance of spirits that rose out of the water, round its small circumference of shore.’ (Journals)

Rydal Mount

‘A paradise…the nicest place in the world for children.’

The Wordsworths lived at the rather grand Rydal Mount from 1813 until their respective deaths. They moved into Rydal Mount just as Wordsworth began his job as a Distributor of Stamps and his fame began to spread due to the publication of his ‘Guide Through the District of the Lakes’. Rather like the house, he had become an establishment figure, much visited by grand people as the years passed. It was here in 1843 that he accepted the honour of becoming Poet Laureate.

Rydal Mount has an unmatchable location. Wordsworth wrote in his memoirs:

‘I observe upon the beauty of that situation, as being backed and flanked by lofty fells, which bring the heavenly bodies to touch, as it was, the earth upon the mountain-tops, while the prospect in front lies open to a length of level valley, the extended lake, and a terminating ridge of low hills.’

Our favourite part of this visit is ‘booing’ along the gravel path along the front of Rydal Mount pretending to write poetry, walking up and down just as Wordsworth did (avoiding the tea tables!)

After trying to get our creative juices flowing, it’s time to join the path again and circumnavigate the southern side of the lakes, crossing a bridge at Rydale Foot. You can also cross via the stepping-stones, but this is a bit touch and go depending on water heights, as Dorothy Wordsworth too had observed: ‘We came home over the stepping-stones, the lake was foamy with white waves. I saw a solitary butter flower in the wood. I found it not easy to get over the stepping-stones.’

One aspect from Rydal Mount, directly south, was ever-present in Wordsworth’s daily discourse on poetic life. Now called Lanty Scar, to Wordsworth it was ‘Aerial Rock’:

‘Aerial Rock–whose solitary brow

From this low threshold daily meets my sight;

When I step forth to hail the morning light;

Or quit the stars with a lingering farewell–how

Shall Fancy pay to thee a grateful vow?’

We reach the steep edge of Loughrigg Terrace, a favoured spot of William and Dorothy.

Dorothy writes: ‘I lay upon the steep of Loughrigg my heart dissolved in what I saw when I was not startled but recalled from my reverie by a noise as of a child paddling without shoes, I looked up and saw a lamb close to me. It approached nearer and nearer as if to examine me and stood a long time.’

Wordsworth celebrates the view from here towards Grasmere in ‘The Excursion’:

‘The Valley, opening out her bosom, gave

Fair prospect, intercepted less and less,

O’er the flat meadows and indented coast

Of the smooth lake, in compass seen: – far off,

And yet conspicuous, stood the old church-tower,

In majesty presiding over fields

And habitations seemingly preserved

From all intrusion of the restless world

By rocks impassable and mountains huge…’

Hammerscar Gorge, which we reach next, is the spot where Wordsworth first saw the Vale of Grasmere as a young boy, walking the six miles or so from his grammar school at Hawkshead, as described in ‘Home at Grasmere’. It begins: ‘once to the verge of yon steep barrier came/A roving school-boy’, and continues:

‘The place from which I looked was soft and green,

Not giddy yet aerial, with a depth

Of Vale below, a height of Hills above.

Long did I halt; I could have made it even

My business and my errand so to halt.

For rest of body ’twas a perfect place,

All that luxurious nature could desire,

But tempting to the Spirit; who could look

And not feel motions there? I thought of clouds

That sail on winds; of breezes that delight

To play on water, or in endless chase

Pursue each other through the liquid depths

Of grass or corn, over and through and through,

In billow after billow, evermore;

Of Sunbeams, Shadows, Butterflies and Birds,

Angels and winged Creatures that are Lords

Without restraint of all which they behold.

I sate and stirred in Spirit as I looked,

I seemed to feel such liberty was mine,

Such power and joy; but only for this end,

To flit from field to rock, from rock to field,

From shore to island, and from isle to shore,

From open place to covert, from a bed

Of meadow-flowers into a tuft of wood;

From high to low, from low to high, yet still

Within the bounds of this huge Concave; here

Should be my home, this Valley be my World.’

This pretty much captures the essence of Lake District beauty to me, first formulated by Wordsworth in his poetry and then baked into the traveller’s mind map by his much-read ‘Guide to the English Lakes’. His guide was an instant success when it was first published in 1810, ‘intended as a Guide or Companion for the minds of Persons of taste, and feeling for the landscape’. Many of the views expressed in it you can hear yourself thinking today!

As we head now towards Grasmere, the prominent crag-topped hill we see towering over the village is Stone Arthur.

Dorothy writes: ‘In speaking of our walk on Sunday evening, I forgot to notice one most impressive sight. It was the moon and the moonlight seen through hurrying driving clouds immediately behind the Stone-Man upon the top of the hill, on the forest side. Every tooth and every edge of rock was visible, and the Man stood like a giant watching from the roof of a lofty castle. The hill seemed perpendicular from the darkness below it. It was a sight that I could call to mind at any time, it was so distinct.’

Of course, this pre-supposes you had set out very late or done the walk very slowly for it to be dark by now.

As we come back into Grasmere, we pay our last respects at St Oswald’s Church, standing by the grave of William Wordsworth which is marked by green signs and metal railings on the east side, with the simple inscription ‘William Wordsworth 1850, Mary Wordsworth 1859’. The neighbouring graves are to his sister, brother and children.

The yew trees in the churchyard were planted, Wordsworth said, ‘under my own eye, and principally if not entirely by my own hand…May the trees be taken care of hereafter when we are all gone’…his words seem to have been heeded.

It is time for us to go now, and we feel a little like Wordsworth in his poem ‘Nab Well’:

‘we must depart, willing or not,

Sky-piercing Hills! must bid farewell to you

And all that ye look down upon with pride,

With tenderness imbosom; to your paths,

And pleasant Dwellings, to familiar trees

And wild-flowers.’

OTHER STUFF

- Read: Dorothy Wordsworth’s ‘Grasmere Journal’, which can be read online at www.gutenberg.org/files/42856/42856-h/42856-h.htm

- Read: ‘Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes’ (1810 & 1835)

- Read: ‘Walking with Wordsworth’ (2010), by Norman and June Buckley

- Read: ‘Wordsworth & The Lake District’ (1984), by David McCracken

- Follow: the High Close tree trail, details at https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/sticklebarn-and-the-langdales/trails/high-close-tree-trail

DIRECTIONS

- Set out eastwards along the road from Stock Lane car park (LA22 9SJ) between Grasmere and Town End, towards Town End; cross the main A591, turn right, then head left up the smaller road past the Wordsworth centre and Dove Cottage on your left.

- Follow this road as it winds up the hill, taking the right turn to White Moss/Ambleside when it is offered; in a few hundred metres, take the metal gate marked Lady Wood just up from the road on the left, following the path that takes the same direction as the road, until it comes back out onto the road.

- Follow the road as it swings round to the left, past a tiny metalled track and a hundred or so metres after turn left off the road up the slope with the quarry on your left, past a small wooden bench; follow this path that winds its way up back to the main path

- Re-join the main path running east along the contour to Rydal Mount, passing Wordsworth’s home on your right. Head right down past the church, turn right along the main road and then soon left across a wooden footbridge

to gain the south side of Rydal Water

to gain the south side of Rydal Water - Where you have a choice of following the path alongside the lake or the higher path, take the higher one, which takes you through a fascinating quarry area towards Loughrigg Terrace, turning left along it and reaching a stone wall at the top of the woods, where you turn right

- Take the next left fork (instead of going on into the NT’s High Close Estate Redbank Wood) and reach Red Bank road; turn right along it, and soon bear off to the left, following the sinuous path through Redbank Wood, past the entrance to Nicholas Wood to eventually re-join the road

- From here you follow the road back into Grasmere; swing around the lake to the right until you are back at the start.

Leave a Reply