Cairngorms: Nan Shepherd

‘I have walked out of the body and into the mountain’

The Inspiration for this walk…The Living Mountain

I must confess I only bought my copy of the Living Mountain in 2022. Like so many, I have come to it late, alerted to it thanks to Robert MacFarlane in his book ‘Landmarks’ where he writes about his ardour for it: ‘I thought I knew the Cairngorms well – until a decade or so ago when I read The Living Mountain, Nan Shepherd’s brief masterpiece about the region. Her prose – born of a lifetime’s acquaintance with the massif – remade my vision of these familiar hills.’

The book, with its evocative front cover, has had exactly the same effect on me, a complete newcomer to the range.

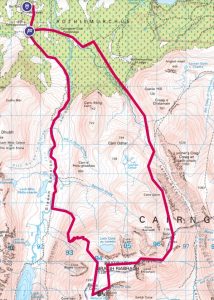

KEY DATA

- Terrain: Navigation can be very difficult on the plateau, and this is a long, tough walk through exceptionally exposed terrain.

- Starting point: Whitewell Parking (NH 9149 0879)

- Distance: 26.9 km (16.8 miles)

- Walking time: 8 hrs 46 mins

- OS Map: https://explore.osmaps.com/en/route/11156712/-Cairngorms-Nan-Shepherd

- Facilities: None

- Overnight option: camp near the Wells of Dee

NAN SHEPHERD (1893-1981)

Nan Shepherd was a Scottish Modernist writer and poet. The Living Mountain, part-memoir, part-field study, was written in the 1940s, reflecting her experiences of walking in the Cairngorms. She chose not to publish it until 1977, but it is now the book for which she is best known.

Since Robert Macfarlane, Jo Simpson and several other well-known outdoor adventurers have championed it in more recent years, it has become something of a cult classic. The Guardian described it as ‘the finest book ever written on nature and landscape in Britain’.

It is her vivid descriptions and observations about the Cairngorms that make it such a pleasure to read. She is ‘a peerer into nooks and crannies’ and for her, the experience of the mountains is more important than Munro bagging. ‘To aim for the highest point is not the only way to climb a mountain’.

Her experience is about the being not about the doing:

‘Yet often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.’

‘Walking thus, hour after hour, the senses keyed, one walks the flesh transparent. But no metaphor, transparent, or light as air, is adequate. The body is not made negligible, but paramount. Flesh is not annihilated but fulfilled. One is not bodiless, but essential body.’

The Glossary of words at the end of the book shows her love of the particular:

Flinchin: deceitful promise of better weather

Legammachy: long story without much in it

Spangin’: walking vigorously

Roarie-bummlers: storm clouds

OUR WALK

We set out through the Rothiemurchus Forest, one of the last fragments of the great Caledonian pine forest. Nan talks of just such an experience: ‘When the aromatic savour of the pine goes searching into the deepest recesses of my lungs, I know it is life that is entering. I draw life in through the delicate hairs of my nostrils.’

We then follow the bubbling Altt Druidh burn upstream.

And so we enter the Lairig Ghru Valley, a great glacial valley that cleaves the Cairngorms Massif into east-west halves. Until the 1920s, the valley was used as a route between Deeside and Strathspey, especially by Drovers taking their livestock to market. By all accounts, Queen Victoria came this way too on a pony trek up to the Devil’s Point and Corrour Bothy.

And so we enter the Lairig Ghru Valley, a great glacial valley that cleaves the Cairngorms Massif into east-west halves. Until the 1920s, the valley was used as a route between Deeside and Strathspey, especially by Drovers taking their livestock to market. By all accounts, Queen Victoria came this way too on a pony trek up to the Devil’s Point and Corrour Bothy.

We toil up the long shoulder of Sron na Lairige, over the tops of Braeriach and, at last, reach the plateau proper: a vast upland of tundra and boulder at an altitude of 4,000 feet. And you never quite know what weather you will find weatherwise, as we are reminded by Nan:

‘Summer on the high plateau can be delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge. To those who love the place, both are good, since both are part of its essential nature.’

Next, we head south over the plateau to reach the top of the Falls of Dee. Peering over, we see the water crashing down 1,000 feet into the Garbh Coire. Nan describes it thus:

‘The young Dee, as it flows out of the Garbh Choire and joins the water of the Lairig Pools, has the same astounding transparency. Water so clear cannot be imagined but must be seen. One must go back, and back again, to look at it, for in the interval memory refuses to re-create its brightness. This is one of the reasons, why the high plateau where these streams begin, the streams themselves, their cataracts and rocky beds, the corries, the whole wild enchantment, like a work of art is perpetually new when one returns to it. The mind cannot carry away all that it has to give, nor does it always believe possible what it has carried away.’

We head southwest across the rocky plateau to the Wells of Dee, the springs that mark the river’s true birthplace and the highest source of any major river in the British Isles. The water rises from within the rock itself. We are making the exact same ‘journey to the source’ as Nan did, confronting matter in its purest form:

We head southwest across the rocky plateau to the Wells of Dee, the springs that mark the river’s true birthplace and the highest source of any major river in the British Isles. The water rises from within the rock itself. We are making the exact same ‘journey to the source’ as Nan did, confronting matter in its purest form:

‘Water, that strong white stuff, one of the four elemental mysteries, can here be seen at its origins. Like all profound mysteries, it is so simple that it frightens me. It wells from the rock and flows away. For unnumbered years it has welled from the rock and flowed away. It does nothing, absolutely nothing, but be itself.’

Then we drop 600 feet north off the plateau in search of Loch Coire an Lochain, which Shepherd prized as one of the range’s ‘recesses’, or hidden places. She had marvelled at the chilly clarity of its water, and its secrecy as a site.

Then we drop 600 feet north off the plateau in search of Loch Coire an Lochain, which Shepherd prized as one of the range’s ‘recesses’, or hidden places. She had marvelled at the chilly clarity of its water, and its secrecy as a site.

‘It cannot be seen until one stands almost on its lip,’ she wrote, ‘the inaccessibility of this loch is part of its power. Silence belongs to it.’

‘The sound of all this moving water is as integral to the mountain as pollen to the flower,’ Shepherd reflects. ‘One hears it without listening as one breathes without thinking. But to a listening ear the sound disintegrates into many different notes – the slow slap of a loch, the high clear trill of a rivulet, the roar of spate. On one short stretch of burn the ear may distinguish a dozen different notes at once.’

The route down to the Gleann Eanaich Valley route is perhaps the trickiest part of the route as the path peters out. Nan would have approved: ‘I like the unpaths best’.

This is a nice Nan quote to finish on:

‘One never quite knows the mountain, nor oneself in relation to it. However often I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me. There is no getting accustomed to them.’

OTHER STUFF

- Listen to: Radio 4 iPlayer’s ‘The Living Mountain’, with Robert Macfarlane

- Listen to: BBC: Slow Radio – Nan Shepherd’s River: The Dee

- Listen to: the audio version of the book – read by Tilda Swinton – it’s absolutely gorgeous.

- Read: Wanderers: Chapter Seven of ‘A History of Women Walking’ (2020), Kerri Andrews

- Read: Chapter Three of ‘Landmarks’ (2015), Robert MacFarlane, p. 55 onwards

- Read: ‘The Corrour Bothy – A Refuge in the Wilderness’, by Ralph Storer, Luath Press. Also some great history by the same author at https://scotlandsnature.blog/2021/08/09/corrour-bothy-a-refuge-in-the-wilderness/

27th April 2022 at 12:35 pm

Dear writer,

I am a native English speaker, living in Germany, and would like to write a doctoral dissertation on slow travel and sustainability in contemporary literature. One of my areas of focus is slow travel in Scottish literature (and in reverse, Scottish literature as a part of slow travel), and I was therefore thrilled to see this blog post. With the several long-distance walking trails in Scotland, do you think it would be possible for a Nan Shepherd trail to be established? Such a trail could perhaps start in Aberdeen (for example Cults, where Nan Shepherd was born), travel to and then through and/or around the Cairngorms, and finish in Aviemore.

I would very much appreciate being in contact with you about how you decided to make this Living Mountain-inspired walk, the direct motivations to do it, the experience of walking, as well as thoughts to a Nan Shepherd trail.

With many well-wishes,

Kelly

10th May 2022 at 5:37 pm

Sadly I am not Anita Sethi, so your message has come to the wrong place. I do a walk featuring her excellent book, and this is what you have seen. best wishes.